Q: What are the canonical effects of a priest fathering a child? A few priests in my diocese have left over the decades in this situation….

A priest being involved in adultery is undoubtedly a horrible sin, at least in part since it very often involves the breakup of another marriage/family. But does a priest fathering a child necessarily involve removal from ministry/laicization? It is certainly a sin, but is it a “canonical crime”? Or is the fact that removal is almost always the case a result of the combination of the priest realizing he now has an obligation to the mother/child that can’t be fulfilled while in ministry and/or the Bishop reacting to scandal? –Patrick

A: It’s tempting for Catholics to think that the scenario described by Patrick is a new problem, perhaps brought on by the increased secularization of modern society and/or a weak spiritual formation in the seminary. In reality, however, this issue has been with us for centuries—because priests, just like the rest of us, have to deal throughout their entire lives with the effects of original sin. Despite their promise of celibacy (c. 277.1, in the case of diocesan priests) or their vow of chastity (c. 599, in the case of many priest-members of religious institutes), members of the Catholic clergy sometimes fall, and in a very big way. (See “The Priesthood and the Vow of Poverty” for more on the distinction between diocesan and religious priests.) You can see historical evidence of this in Canon 3 of the Council of Nicaea—the Church’s very first Ecumenical Council, convened in 325 A.D.—which forbade all clergy to live with any woman except a mother, sister, or aunt. That the 4th-century Council Fathers felt the need to address this issue at all speaks volumes about what was apparently going on at the time!

It goes without saying that when a woman is pregnant and a priest is established to be the father, this will cause an enormous scandal if it becomes public knowledge. But how does canon law fit into the equation? Before we can answer this question, it’s necessary to make an important distinction, between actions which are sinful, and actions which are illegal. Let’s take a look at the basic difference.

Many non-canonists, both Catholics and non-Catholics, honestly think that what canon lawyers do for a living involves finding people guilty of mortal sin and maybe even condemning them to hell. (Yes, really!) In actual fact, “sin” is fundamentally a matter for moral theologians, not for canon lawyers, and it is routinely dealt with in what the Church calls the internal forum. As a rule, the internal forum refers to matters confessed in the sacrament of Penance, and to discussions with a priest that occur in the context of spiritual direction. In other words, the internal forum is private, and unless the penitent or spiritual directee chooses to repeat what happened there, nobody else will ever hear about it.

This is one big reason why the vast majority of sins aren’t even mentioned in the Code of Canon Law! Speaking broadly, our personal moral failings ordinarily do not affect our legal status within the Church. They are humbly confessed to the priest in persona Christi, and then forgiven, thanks to the infinite generosity of God Himself—Who then considers these matters to be closed. Think of a Catholic who has committed theft, or smacked his wife, or lied to his boss: these sorts of actions obviously offend God and also cause harm to other people, but they don’t necessarily have any effect on the perpetrator’s role within the Church or on the Church itself. They are certainly sinful, but they are not illegal under canon law.

At the same time, as we all know, there are some actions which are morally wrong in themselves, and by their very nature create some kind of disruption within the Church. To cite only a few examples, when a Catholic theologian teaches heresy to seminarians (see “Was Theologian Hans Küng Ever Excommunicated?” for more on this scenario), or a non-priest “celebrates Mass” invalidly for the faithful (an issue discussed in “How Can You Tell a Real Priest From a Fake?”), or someone traffics in Mass stipends (see “Mass Intentions and Stipends (Part II)”), these are acts which cause spiritual harm and also damage the fabric of the Church. As a general rule, it is these sorts of immoral actions which are illegal actions as well.

So how would a priest getting a woman pregnant fit into this equation? Clearly it’s an immoral action, but is it actually illegal too? The short answer could be summed up as, “It depends.”

Think about it this way: morally speaking, what’s the difference between a priest having sex with a woman and getting her pregnant, and a priest having sex with a woman and not getting her pregnant? The fact is, what’s morally wrong here is the sexual activity itself—whether it results in a pregnancy or not. And while the Code of Canon Law clearly asserts the Church’s teaching that our clergy are to maintain celibacy (cc. 277.1 and 599 again), it does not attach a specific sanction to violations. If you consider what was just said above about canonically illegal actions creating some kind of disruption within the Church, this should make sense: it’s entirely possible for a priest to fail to observe celibacy, without anyone (other than the woman involved, of course) ever knowing about it. Remember that if he sincerely confesses this sin, it will be forgiven—and as was discussed at length in “Can a Priest Ever Reveal What is Said in Confession? (Part I),” the priest who grants him absolution in the confessional cannot mention it to anyone.

That said, there is a particular context in which this sexual activity could very well be construed as illegal. Canon 1378.1 (which used to be the old canon 1389.1, see “Is it a Sacrilege to Hit a Priest?” for more on the recent rewrite of the chapter on Sanctions in the Code of Canon Law) tells us this:

A person who, apart from the cases already foreseen by the law, abuses ecclesiastical power, office, or function, is to be punished according to the gravity of the act or the omission, not excluding by deprivation of the power or office…

Let’s imagine that a parish priest finds a female member of the parish attractive—and he uses his status as the head of her parish to pressure her into submitting to his sexual advances. Let’s say that ordinarily she never would have agreed to such a thing, but she was intimidated and felt she couldn’t say no. In such a case, you could certainly make the argument that the priest “abused [his] ecclesiastical power, office, or function” as described in canon 1378.1 (cf. also the new c. 1395.3, which would likewise apply if the parish priest actually forced/threatened her); and so if the woman were to alert the priest’s superiors to what had happened, the priest could be sanctioned. He might even lose his ecclesiastical office—regardless of whether the woman got pregnant or not, or whether this became public knowledge or not (see “When Can a Pastor be Removed From Office?” for more on this issue). In this scenario, what’s being punished is not “merely” the priest’s sinful sexual activity, in and of itself; it’s the fact that he had been placed in a position of authority within the parish, and he harmed a member of the parish faithful by abusing that authority. In other words, this would constitute an act “which causes spiritual harm and also damages the fabric of the Church,” as was discussed above—and that is why it would be illegal as well as sinful.

By this point, it should be clear that Patrick is definitely onto something. He makes exactly the right distinction between “sin” and “canonical crime,” and that’s why his suspicions are fundamentally correct. Technically, there are no “canonical effects of fathering a child,” in and of itself.

He’s also on the right track when he refers to the scandal which naturally accompanies public revelation of this kind of sinful activity. When a priest’s sexual affair becomes public knowledge, this publicity in itself doesn’t necessarily make the activity illegal … although it certainly might be a contributing factor. Let’s imagine that a priest has been having a sexual affair with a woman of the parish for some time—and finally word gets out about what’s been going on. Imagine that the whole parish now knows about it … but the priest defiantly continues to see the woman, just as before! Let’s say that when the bishop is informed of the uproar, he instantly orders the priest to stay away from the woman (among other things), but the priest disobeys, and is seen visiting her again. In these particular circumstances, canon 1395.1 would apply: among other things, this canon deals with “a cleric who continues in some other external sin against the sixth commandment of the Decalogue which causes scandal,” and tells us that he “is to be punished with suspension.” (See “Father Pavone’s ‘Suspension’: Priests for Life, Part II” for more on the sanction of suspension, which can only be applied to clergy.) Of critical importance in canon 1395.1 is the word “continues,” because this implies that (a) scandal has already been given, and (b) the priest who caused it is making no effort to end it, much less to repair it. Once again, this extreme scenario (which has indeed happened!) would amount to an act that causes spiritual harm and also damages the fabric of the Church, which is the reason why it would be illegal and punishable by a sanction.

By the way, given its wording, there’s a flip-side to canon 1395.1: if a priest has been found to have engaged in an “external sin against the sixth commandment,” but immediately ceases that activity when it is discovered, he cannot be sanctioned under this particular paragraph. But that brings us to canon 1395.2, which tells us this:

A cleric who has offended in other ways against the sixth commandment of the Decalogue, if the offence was committed in public, is to be punished with just penalties, not excluding dismissal from the clerical state if the case so warrants. (Emphasis added.)

Note that once again, a critical factor here is whether or not the cleric’s sexual activity has become public knowledge or not—because the Church’s concern is with scandal caused to the faithful. As Patrick rightly observes, sometimes the situation involves a married woman, and when it becomes public knowledge, her whole family suffers under the fallout. In this situation, the priest’s bishop/religious superior can sanction the priest under canon 1395.2.

Now let’s contrast this with a scenario in which a priest has been sexually involved with a woman who gets pregnant … and she gives the baby up for adoption, officially declaring that the father is “unknown.” Maybe she doesn’t even tell the priest-father that this has happened and that she has done this! Under these circumstances, nobody apart from the priest and the woman has a clue what has been going on between them: in other words, there is no public scandal. Let’s say that each of them subsequently repents of what they’ve done, goes to confession, and resolves to sin no more—and that’s the end of it. There is no canon law involved here at all. See the difference?

Unfortunately, not every situation is so neat and tidy! If a woman gets pregnant and wants to keep the baby, and she openly tells others that the father happens to be the parish priest, whom she would like to marry in order to raise the baby in an intact family … it goes without saying that this can be a real mess. There is little question of the priest continuing to minister in the parish as before; the scandal has undoubtedly destroyed his reputation and his credibility before the parish faithful. Generally he will request laicization, which in canonical parlance is called “losing the clerical state” (cc. 290-293), as was discussed at length in “Can a Priest Ever Return to the Lay State?” Note that while Patrick references a priest’s “removal,” not all laicization constitutes an involuntary punishment: sometimes a priest freely asks for it, although in other cases the Church dismisses a priest from the clerical state as the ultimate sanction (think “Cardinal McCarrick,” and see “What Does it Mean to ‘Defrock’ a Priest?”). If Rome is made aware of a situation involving a pregnancy and a priest who wants to marry the mother of his child, it can grant his request for laicization and even release him from his promise of celibacy (c. 291), enabling him to marry the woman and live henceforth as a layman.

Patrick asked a great question, didn’t he? Now he has his answer. As it has done throughout its nearly 2000-year existence, the Catholic Church wants to balance its desire to forgive the sinner (a theological matter) with protecting the Church’s own integrity and avoiding scandal (which as we’ve seen, quickly becomes a canonical matter). Perhaps the best take-away is the need to pray for our priests, that they remain strong in the face of temptation and faithful to the promises they have made to God.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

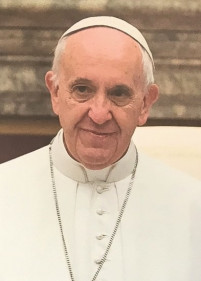

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.