Q: I don’t need to tell you, practically the whole Catholic world is looking at the removal of Bishop Strickland from [his diocese of] Tyler, [Texas,] and wondering what happened and why. From the perspective of canon law, what did the Pope do procedurally? Was it a valid action? … My Catholic friends and family are confused… —Mirella

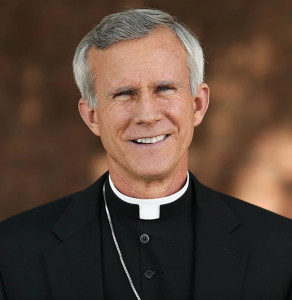

A: In case you missed it, Mirella is referring to Pope Francis’s recent removal from office of Bishop Joseph Strickland, who for over a decade served as the Bishop of the Diocese of  Tyler, Texas. No official reason for this highly unusual action was given by either the Pope or anyone else in the Vatican—and this has naturally resulted in a lot of speculation and concern not just in Texas, but around the world.

Tyler, Texas. No official reason for this highly unusual action was given by either the Pope or anyone else in the Vatican—and this has naturally resulted in a lot of speculation and concern not just in Texas, but around the world.

Some well regarded canonists have publicly opined as to the process (or lack thereof) that led to Bishop Strickland’s removal, and in some cases their reasonable theories and conclusions are markedly different and even contradict each other. Let’s take a look at some of these opinions, and also at what canon law has to say—and just as importantly, what it doesn’t say—about removing a diocesan bishop from his office, and at the necessary procedure to do this properly. Then we’ll see what, if any, conclusions can be drawn from what has happened.

But before we start, there is one key part of Mirella’s question that can be answered immediately and unequivocally: was the removal of Bishop Strickland from office valid? Regardless of whether or not you like what happened, or want to argue that canonical procedure was not followed correctly, the answer is clear. The Pope possesses “full and supreme power in the Church” (c. 332.1) and “by virtue of his office, the Holy Father not only possesses power over the universal Church but also obtains the primacy of ordinary power over all particular churches” (c. 333.1). (In case you’re wondering, the term “particular church” describes a number of entities, but the overwhelming majority of particular churches are dioceses, as per canon 368.) It is the Pope who decides which men are to be bishops of which dioceses, in accord with canon 377.1, and so it is only logical that the Pope likewise can determine which men are not to head dioceses, or hold other offices traditionally entrusted to bishops. Thus if the Pope has said (justifiably or not!) that Bishop Strickland has been removed from his office, then that basically settles it. See “Are There Any Limitations on the Power of the Pope?” for more on this topic.

Sure, in theory the Pope could later rethink his decision in this, or any other matter, and could revoke his earlier decree; but otherwise, a decree of the Holy Father is final, and cannot be appealed to anyone on earth. “The First See is judged by no one,” declares canon 1404—a canon discussed in another context in “Could a Pope Ever Be Excommunicated? (‘Excommunication’ Defined).” Consequently, Catholics can safely assume that since Pope Francis has said that Bishop Strickland is no longer the Bishop of Tyler, that means Bishop Strickland is no longer the Bishop of Tyler. Period.

The next logical question is, why isn’t Bishop Strickland the Bishop of Tyler any longer? What were the grounds for the Pope’s decision? Well, nobody knows! The official notice from the Vatican Press Office simply says,

The Holy Father has removed Bishop Joseph E. Strickland from the pastoral care of the diocese of Tyler, United States of America, and has appointed Bishop Joe Vásquez of Austin as apostolic administrator of the same diocese, rendering it sede vacante.

The fact that the notice indicates that the bishop has been “removed,” and the office of bishop is now vacant, tells us clearly that this constitutes a permanent change—not a leave of absence, or some other sort of temporarily impeded situation. This is obviously not a case of (let’s say) a diocesan bishop who just underwent surgery and needs time to convalesce; or a political problem in a region where the Church is currently being attacked by officials hostile to our faith—rendering the local bishop unable to govern his diocese until the politics change. In situations like these, the circumstances can (at least potentially) improve, and the bishop can eventually return to the work of leading his diocese. But as it is, Bishop Strickland is gone for good, and right now there is no Bishop of the Diocese of Tyler, Texas. And at this point, since neither Pope Francis nor the Vatican spokesmen have proffered any explanation, and we can’t get inside the mind of Pope Francis, we don’t know why.

So we will leave that pivotal question aside for the moment, and ask another question, one that is obviously related but much broader: procedurally speaking, how does a diocesan bishop cease to be bishop of his diocese? As with so many legal questions, the short answer is, it depends! Let’s now look at existing law and other Vatican documents that are relevant to this issue; and then, as mentioned earlier, we’ll look at the way that different canon lawyers are interpreting it, and what they are concluding with regard to what happened in the Strickland case.

Canon 193.1 provides us with a relevant general norm, declaring that a person cannot be removed from an office conferred for an indefinite period of time [like the office of diocesan bishop] except for grave causes and according to the manner of proceeding defined by law. Fine—except that since we don’t know what the “grave causes” were in the Strickland case, it’s pretty hard to determine whether it was done in accord with the law or not (more on this later).

Let’s move forward. Canon 416 lists the various ways in which the office of diocesan bishop is made vacant:

An episcopal see is vacant upon the death of a diocesan bishop, resignation accepted by the Roman Pontiff, transfer, or privation made known to the bishop.

As we saw earlier, the Vatican Press Office has stated publicly that the office of Bishop of the diocese of Tyler, Texas is now vacant, and thus this canon is immediately relevant to us—so let’s look at each of the possible options it contains. Bishop Strickland obviously didn’t die; he didn’t resign (although he says he was asked to do so, and refused); and he was not transferred to a different diocese. All that remains is “privation made known to the bishop.” What does this mean? Canon 196.1 has the answer: Privation from office, namely, a penalty for a delict, can be done only according to the norm of law. The next paragraph adds that privation takes effect according to the prescripts of the canons on penal law (c. 196.2).

The “canons on penal law” constitute an entire book of the code (Book VI, canons 1311-1399) plus part of Book VII, which contains procedural law (Part IV, “The Penal Process,” canons 1717-1731). Addressing all of these canons would require an entire book—a number of which have already been written by other canonists, in various languages—and is beyond our scope here. Suffice to say that if any Catholic, bishop or not, is accused of a canonical crime, there must be a proper investigation (cc. 1717 ff.) and a trial (cc. 1721.1 ff.), which obviously means that the accused is made aware of the allegation(s) and given the opportunity to defend himself. In general, this is much like a criminal trial in the world of civil law.

True, there’s a procedural loophole in canon 1720, whereby the judge (who would be the Pope himself, if a diocesan bishop were accused of a crime) can issue an extrajudicial decree, bypassing a penal trial … but even in this situation, the accused must first know what he’s being accused of, and have the chance to defend himself.

If your head is spinning at this point, you have plenty of company! Armed with all the above information, different canonists have reached different conclusions about what actually happened, in the legal sense, when the Pope removed Bishop Strickland. This canon lawyer argues that Pope Francis failed to follow canonical procedure in this case, violating natural justice. His logic—which is undeniably solid—basically goes like this:

1. Bishop Strickland was deprived of his office, as is mentioned in canon 416 (discussed above).

2. Privation of office is a penalty, which can be imposed only if one is found guilty of having committed a crime (or in canonical parlance, a delict), as per canon 196.1, referenced above, and also canon 1336.4 n.1.

3. There was no judicial penal process or administrative process against Bishop Strickland, who has not been accused of any crime.

Yes, it is true that in July 2023, the Vatican ordered an apostolic visitation of the Diocese of Tyler, Texas, sending two bishop-visitors to investigate the situation there—but an apostolic visitation most certainly does not constitute a penal trial. The term apostolic visitation is officially defined in the Apostolic Constitution Praedicate Evangelium (PE), which lays out the current offices in the Vatican Curia and their respective duties:

In cases where the correct exercise of the episcopal function of governance calls for a special intervention, and the Metropolitan or the Episcopal Conferences are not able to resolve the problem, it falls to the Dicastery [of Bishops], if necessary in accord with other competent Dicasteries, to decide upon fraternal or apostolic visitations and, proceeding in like manner, to evaluate their outcome and to propose to the Roman Pontiff the measures deemed appropriate. (Art. 107.2)

(We took a look at PE in another context in “Can Laypeople Hold Top Vatican Positions?”)

Note that an Apostolic Visitation is prompted by the inability of an Episcopal Conference “to resolve the problem” in a given diocese—but once again, nobody knows for sure what “the problem” was in the Diocese of Tyler.

Canons 1717-1731 explain the penal process, which is to be used when someone in the Church is accused of a crime. In such a process, the accused is of course informed of the allegation(s) against him, and has the opportunity to defend himself, much like a criminal trial in the world of civil law.

4. Consequently, Bishop Strickland’s “removal was by means of an act of the pope apart from existing canonical procedures.”

This same canonist is careful to note that the Holy Father does indeed have the power to remove a bishop, even extra-legally (as was already discussed above); but he concludes that by failing to follow established legal procedures, Pope Francis’s action directly conflicts with what Pope Saint John Paul II declared in his Apostolic Constitution Sacrae Disciplinae Leges, promulgating the Code of Canon Law that is still in effect today. John Paul II declared that the whole purpose of the code was to create “an order in the ecclesial society,” and he observed that “since, indeed, [the Church] is organized as a social and visible structure, it must also have norms…” In other words, the Church should not be ruled by arbitrary whims, but by laws—and the removal of Bishop Strickland appears to have been done in accord with the former, rather than the latter.

There’s no denying that this canonist is making valid points! That said, other canon lawyers have examined the situation and reached different conclusions. This well known canonist has stated that since there’s no evidence that Bishop Strickland was removed as a penalty for a crime—which, as noted above, would require the accused to be aware of the accusation(s) and given the opportunity to present a defense—but as an “administrative removal.”

Where are the canons explaining why, and how, to remove a bishop administratively? This canonist rightly observes that there aren’t any—but notes that there is a clear parallel in canons 1740-1752, on the removal of pastors from their parishes. We took a look at these canons in detail in “When Can a Pastor Be Removed from Office?” but in short, canon 1740 declares that

When the ministry of any pastor becomes harmful or at least ineffective for any cause, even through no grave personal negligence, the diocesan bishop can remove him from the parish.

Note that that the pastor of a parish can be removed even though he committed no crime—after a legal process that is administrative, not penal.

The canonist reasonably concluded that a parallel process can be construed to exist in the Church, although that process is not part of the Code of Canon Law, and is not known publicly to the Church as a whole. “I don’t know that they [the Vatican’s Dicastery for Bishops] have a process with criteria,” he said. “If there is, it’s not been published, and so it’s not available to canon lawyers to critique.” This canon lawyer pointed out that if a process for the administrative removal of bishops does exist somewhere on paper, it should be made known, at least to “eliminate some of the innuendo and suspicion of arbitrariness.”

So in conclusion, what are we to make of this whole sorry situation? Regardless of what you think of the abovementioned canonists’ opinions on what happened to Bishop Strickland, it’s difficult to deny that (a) there is no known reason why the Pope decided to remove the bishop from his office; and (b) there is no canonical process (penal or administrative) that is known to have been followed correctly. In short, there has been no transparency. We Catholics shouldn’t be scratching our heads, and canonists shouldn’t need to write articles trying to figure out what happened here—because it should be perfectly obvious! Instead, all that is obvious is that we need to pray for the Church, and particularly for its leaders. There’s a good reason why Pope Francis so often asks people to pray for him (see here in 2015, and in 2016, and in 2017, just to name a few) —so let’s do it.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.