Q1: According to this article, a seminarian in New York was kicked out of the seminary because he complained about his spiritual director. What concerns me is that the article says that according to canon law, seminarians can freely choose their spiritual director, but in this case the seminarian was forced to talk to this particular one…. What recourse does a seminarian have, if his rights are being violated like this? It’s incredible that we have a shortage of vocations, and yet seminary officials hound men out of the seminary like this… –Charles

Q2: I was in minor seminary, but eventually found out that the priestly vocation is not what God wants from me. So I left, but some of my friends proceeded further towards ordination. One of them told me one time that he had homosexual feelings, and, although he had a few interactions with the same sex (as I understood, one time it was real interaction), he claimed that he didn’t have deep-seated homosexual tendencies because he was also in love with girls and he is not effeminate, etc. Also he does not support the gay culture and is no longer practising homosexual acts. His ex-spiritual director advised him to leave the seminary, but he stayed and has a new spiritual director, and he decided not to tell him anything.

So, my question is: will he, if it comes to it, be properly ordained if he does not tell the spiritual director anything? Or if he does tell the new spiritual director, and he likewise tells him to leave the seminary but he proceeds to ordination anyway, will he be properly ordained? –Piotr

A: Many Catholics may be unfamiliar with the concept of a spiritual director, and thus might have difficulty appreciating his importance in seminary life. We all understand what a confessor is, since all Catholics above the age of reason are expected to seek the sacrament of Penance regularly; but “confessor” and “spiritual director” aren’t synonymous terms. You might say that spiritual direction takes the aspects of confession pertaining to spiritual counsel and advice to another level. Any Catholic, seminarian or not, can ask a holy, experienced priest to meet with him regularly and discuss his spiritual life in greater detail than normally occurs in confession—not just in order to avoid sins, but also to try to practice the virtues more perfectly and achieve a higher level of spiritual perfection.

As any priest will tell you, studying theology and philosophy is an integral part of seminary life, and so it’s critical that academic courses be well taught and impart solid, orthodox Catholic teachings. Yet the spiritual formation which seminarians receive is also critical—because not only should a priest be well educated, he likewise should be trained in how personally to live a virtuous life, directed to God. The Church doesn’t just want her priests to be knowledgeable; she wants them also to be holy! This is why it’s so important for Catholic seminaries to provide seminarians with access to solid spiritual directors who are themselves experienced in the spiritual life, and are doing their level best to achieve the level of holiness that God wants for them. In many ways a spiritual director serves as a sort of personal mentor for the priest-in-training—and all of us Catholics should naturally want those mentoring our future priests to get it right.

What is a spiritual director supposed to do with/for the seminarian? In 2005, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (see “Are Catholics Supposed to Abstain from Meat Every Friday?” for more on what a Conference of Bishops is) put together the latest Program of Priestly Formation for seminarians in their territory. While this document is not binding on the Church in the rest of the world, Catholics who live elsewhere can nevertheless find here guidelines that correctly apply the canons on this subject to practical, everyday seminary life. Among many other things, the Program describes the role of a seminarian’s spiritual director:

Seminarians should meet regularly, no less than once a month, with a priest spiritual director. Spiritual directors must be chosen from a list prepared by the director of spiritual formation. They should have proper training and adequate credentials for the work. These priests must be approved by the rector and appointed by the diocesan bishop….

Seminarians should confide their personal history, personal relationships, prayer experiences, the cultivation of virtues, their temptations, and other significant topics to their spiritual director. If, for serious reason, there is a change of director, the new director ought to give attention to continuity in the seminarian’s spiritual development.

The spiritual director should foster an integration of spiritual formation, human formation, and character development consistent with priestly formation. The spiritual director assists the seminarian in acquiring the skills of spiritual discernment and plays a key role in helping the seminarian discern whether he is called to priesthood or to another vocation in the Church. (127-129)

That’s specific guidance for the Church in the United States—but the Code of Canon Law, which of course pertains to the universal Church, speaks far more briefly and generally about the role of the spiritual director at a seminary. Canon 239.2 stipulates the need for every seminary to have at least one spiritual director; and canon 246.4 tells us that all seminarians should have a spiritual director to whom they can trustfully reveal their conscience—and that this spiritual director should be freely chosen by each seminarian. In other words, if there are multiple spiritual directors at a seminary, nobody has the authority to assign a particular director to a particular seminarian. The seminarian has the right to make this decision himself; and if that seminarian finds that it isn’t a good fit—perhaps due to a perfectly natural clash of personalities, the seminarian feels very uncomfortable entrusting his director with his inmost personal thoughts—he may later decide to switch to a different director. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this, and it certainly does happen. Note that the opposite can occur too: a spiritual director might conclude that for reasons of temperament (for example), it would be best for a seminarian to seek his spiritual direction from someone else.

Thus Charles’ question is already answered. If you read the article that he references, it certainly sounds like the seminary staff laid a trap for this particular seminarian, in order to get rid of him—by insisting that he had to go to a particular priest for spiritual direction, even though he already had a spiritual director and didn’t want a new one. After he complained to superiors about the homosexual bent of this spiritual director who had been imposed on him, the staff then claimed that they hadn’t imposed anything on him! While it’s always risky to draw definitive conclusions based on a single news article, it does seem clear that canon law was violated in this case. And Charles is undoubtedly correct, that when other, prospective seminarians hear horror-stories like this one, they will naturally want to give that diocese/seminary a very wide berth. See “Why Would a Bishop Refuse to Ordain a Seminarian?” for more on this general topic.

Piotr’s question is more complex. Although he is using some terminology here which is a bit ambiguous, Piotr’s context is clear. Rephrased in more precise canonical terms, his two-part question is this: is a seminarian validly ordained, if

(a) he has been concealing information from his spiritual director that would presumably prompt that director to urge him to leave the seminary? or

(b) he was told by his spiritual director to leave the seminary but refused to go, and was then ordained by a bishop who had no knowledge of the real situation?

If you appreciate the significance of a spiritual director in the life of a seminarian, the situation which Piotr describes makes perfect sense. A seminarian who is struggling with an attraction to members of the same sex ought naturally to discuss this with his director; and it is only logical that the director will try to help him address such matters from a spiritual perspective.

As was discussed at length in “Can Homosexual Men be Ordained to the Priesthood?” the Vatican’s 2005 Instruction Concerning the Criteria for the Discernment of Vocations with regard to Persons with Homosexual Tendencies in view of their Admission to the Seminary and to Holy Orders stated unequivocally that the Church “cannot admit to the seminary or to holy orders those who practice homosexuality, present deep-seated homosexual tendencies or support the so-called ‘gay culture.’” That said, if Piotr’s seminary-classmate acknowledged having “homosexual feelings in the past,” this doesn’t automatically mean he has the sort of “deep-seated homosexual tendencies” referred to in this document (although it might). Given today’s sex-crazed culture, where young men and women are being constantly bombarded with sexual images and ideas, nobody should be surprised that even a spiritually and mentally healthy seminarian might find himself raising questions in his mind about his own sexuality. What Piotr says of his fellow-seminarian’s past sexual tendencies could very well have been a temporary period of confusion in the man’s life, which by now has been sorted out for the good.

Yet at the same time, if after extended discussions a spiritual director concludes that the seminarian has serious, fundamental issues that in his estimation render the seminarian ill-suited to the priesthood … then the director could certainly encourage him to seriously rethink God’s purpose for his life, and to leave the seminary altogether. Once again, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with this; many Catholic men around the world have initially thought that they had a vocation to the priesthood, but after testing it in the seminary they have realized that they’re meant to live a different sort of life in the world. If both the spiritual director and the seminarian are on the same page about this, the basic procedure is pretty straightforward: the seminarian will inform his superiors of his decision to leave, and then make the necessary arrangements to do just that.

But as we can see from Piotr’s question, it’s not always so simple. It could very well happen that a spiritual director feels quite strongly that a seminarian should not be ordained a cleric—yet the seminarian disagrees and wants to continue. If the seminarian’s bishop or religious superior honestly has no inkling of the issues discovered by the director during his discussions with the seminarian, then there may be nobody standing in the way of his ordination. What can the spiritual director do?

Canon 240.2 gives us a clear answer: nothing. When the administration of a seminary is making decisions about admitting a seminarian to holy orders or dismissing him from the seminary, input is never to be sought from the spiritual director or the seminarian’s confessor(s). We Catholics are all aware that a confessor is bound by the seal of confession, and can never reveal or act on the information he hears in a confession (as was discussed in “Can a Priest Ever Reveal What is Said in Confession? Part I” and “Part II”); but most Catholics are far less familiar with the obligations of a spiritual director—whose discussions with his seminarian-directee are part of what is known as the internal forum. The abovementioned Program of Priestly Formation once again has a clear discussion of the requirements for confidentiality that are placed on a seminarian’s spiritual director:

Disclosures that a seminarian makes in the course of spiritual direction belong to the internal forum. Consequently, the spiritual director is held to the strictest confidentiality concerning information received in spiritual direction. He may neither reveal it nor use it. The only possible exception to this standard of confidentiality would be the case of grave, immediate, or mortal danger involving the directee or another person. If what is revealed in spiritual direction coincides with the celebration of the Sacrament of Penance (in other words, what is revealed is revealed ad ordinem absolutionis), that is, the exchange not only takes place in the internal forum but also the sacramental forum, then the absolute strictures of the seal of confession hold, and no information may be revealed or used. (134)

Since spiritual direction takes place in the internal forum, the relationship of seminarians to their spiritual director is a privileged and confidential one. Spiritual directors may not participate in the evaluation of those they currently direct or whom they directed in the past. (333)

So a spiritual director is not to volunteer his opinion of the suitability (or lack thereof) of a particular candidate for the priesthood. At the same time, the seminarian’s superiors, including his bishop and the seminary rector, are not to ask the spiritual director for his opinion. One may reasonably hope that if a seminarian’s spiritual director sees red flags that lead him to conclude the seminarian isn’t cut out for the priesthood, that others at the seminary will see them too—and in fact it does happen that multiple authorities can see the same warning signs, and then reach the same conclusion about a particular seminarian, without any unlawful input from his spiritual director. Nonetheless, if we return to Piotr’s specific case, if a spiritual director told a seminarian flat-out that he’s clearly not meant to be a priest, but the seminarian didn’t agree, and his superiors approved of his ordination … there’s little the spiritual director can do, besides pray for all involved.

Would hiding information about his sexuality affect the validity of the seminarian’s ordination? Well, as was discussed at length in “Can a Priest Have His Ordination Annulled?” it’s actually very easy to ordain a priest validly. So long as the ordaining bishop has the correct intention, uses the correct form of words, and imposes his hands on the man to be ordained, the ordination is considered valid. This means that if Piotr’s fellow-seminarian conceals information from his spiritual director and/or his bishop, it doesn’t affect the validity of his ordination. Granted, the morality of such an action could and should certainly be questioned, if others eventually find out! But the man would nonetheless be a validly ordained priest.

By now the importance of a spiritual director in the life of a seminarian should be evident. The formation of future priests isn’t just a matter of academics; a critical part of that formation focuses on their personal spirituality. Since it’s important to be able to trust a person to whom a seminarian confides his internal, private thoughts, the Church has instituted safeguards to protect his privacy—similar to the seal of confession, although not quite as stringent. In return, a seminarian should be honest with his spiritual director, not deliberately hiding relevant matters from him out of fear of repercussions. We’re probably all praying for our seminarians already, but let’s pray for them all once again, right now, that they will be well formed into truly holy priests.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

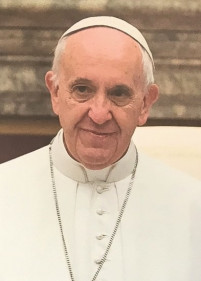

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.