Q: Canon law makes marriage illicit, not invalid. In your article “Are SSPX Sacraments Valid,” you quoted Canon 1108.1 that if the marriage isn’t celebrated in front of the bishop, pastor, or his designee, then “the marriage is invalid.”

But Canon Law, and even the keys of Peter, has no power to determine that.

…Illicitness (sic) is fully in the power of Canon Law to determine…. But (in)validity…is in the Power of God the Holy Spirit, and so invalidity occurs purely in the Order of Grace, and Canon Law can’t touch, change, affect, or determine that in any way.

Isn’t it true that the only difference between sacramental and non-sacramental marriage is the presence (or absence) of the Holy Spirit in the 2 spouses? Therefore… for a marriage to be invalid, there would have to be an absence of Sanctifying Grace, i.e. Mortal Sin. So this sacrament is effected (to be) valid or invalid primarily in the Order of Grace, not in the order of Canon Law.

Marriage tribunals, operating under Canon Law can only attempt to “guess at it,” after the fact; but ultimately it is God who decides whether there’s a real marriage there. Canon 1108.1 should’ve said (if it were to be more accurate), “the marriage is SUBJECT TO possible invalidity.” –David, Theology summa cum laude, X College

A: It’s not clear what prompted David to send in this astonishing and heretical statement, which readers will notice does not contain a question. Perhaps he just discovered the five-year-old article which he references, and doesn’t like what the Catholic Church teaches on that subject.

In any event, there are two separate issues here worth discussing. The first one is, who has authority to determine what is necessary for a Catholic sacrament to be valid? David apparently thinks that the answer is “nobody.” Reality is, of course, rather different.

The second issue involves the fact that David boasts of an undergraduate degree in theology from a Catholic college in the United States, which routinely identifies itself as providing “a truly Catholic education in fidelity to the Magisterium of the Catholic Church.” It is, therefore, all the more disturbing that the school has awarded high honors to a graduate who, as we see here, is willing to go on the offensive in order to attack not only Catholic teaching, but the very structure of the Catholic Church as Christ founded it. Let’s take a look at what the Church’s real teaching is on this subject, and why.

The Catholic Church has established what is necessary for the valid celebration of each of the seven sacraments. Who exactly has the authority to make decisions about such things? Canon 841 gives us the answer, which isn’t terribly surprising: since the sacraments are the same throughout the universal Church, and belong to the divine deposit of faith, only the supreme authority in the Church can approve or define what is needed for their validity. In canon law, the phrase “supreme authority in the Church” is sometimes used to refer either to the Pope himself, or to the College of Bishops acting together with the Pope as their head (as in an ecumenical council, for example).

Note that this canon doesn’t merely tell us that the Pope can decide what constitutes a valid sacrament and what doesn’t; it also provides both practical and theological reasons why this is so. On the practical level, we all know that the Catholic Church exists all over the world, and numbers over one billion members at the moment. It’s only common sense that in order to ensure that it celebrates the same sacraments consistently everywhere, there must be one source for the fundamental rules concerning their valid celebration. And since we Catholics share, by definition, the same faith, the same sacraments, and the same governance (c. 205), we naturally look to the Pope, who is the head of the Church on earth, to determine what is required for everyone. As canon 12.1 tells us, universal laws like these are binding everywhere. This is not rocket-science, and should come as a surprise to no one.

Canon 841 also points out that there’s a huge theological reason why it is for the supreme authority in the Church to determine what’s necessary for the valid celebration of the sacraments: they belong to the divine deposit of faith. The Catholic Church teaches that the seven sacraments were given to us by God—not invented by man. In other words, the sacraments are part of revelation, and belief in their necessity and spiritual efficacy is a requirement of the Catholic faith (cf. c. 750.1). Determining how exactly they are to be celebrated is a practical but theologically very important matter, which is naturally left up to the head of the Church on earth.

For the record, canon 841 was promulgated as part of the 1983 Code of Canon Law by Pope St. John Paul II. Before promulgating the new code, this Pope looked at every single canon of the proposed draft—all 1,752 of them!—together with a team of canonists; and he either approved of them as written, or in a few cases had them altered himself.

But the current canon 841 wasn’t created out of the blue in 1983. Its substance was already contained in canon 733.1 of the previous, 1917 Code of Canon Law, which asserted the same thing in different words. And where did the authors of the 1917 code get it from? From the Council of Trent.

The Council of Trent took place in the 16th century, in response to the theological chaos caused by the protestant reformation. In 25 sessions held intermittently over the course of 18 years, the bishops of the Catholic Church met in this ecumenical council in order to discuss the theological and disciplinary questions which had been raised by the writings and statements of Martin Luther and many other reformers of that era. And one of the matters they discussed was the authority of the Catholic Church to determine what constitutes a valid sacrament—including the sacrament of marriage.

Marriage was a hot-button issue during the reformation, in great part because Martin Luther had attacked the notion of priestly celibacy, claiming that it was unrealistic to  require sexual abstinence of the clergy. Luther, who was himself a Catholic priest and a member of the Augustinians, encouraged the clergy to marry, and eventually got married himself.

require sexual abstinence of the clergy. Luther, who was himself a Catholic priest and a member of the Augustinians, encouraged the clergy to marry, and eventually got married himself.

The theological implications of Luther’s teachings on marriage are extremely complex, and so it is impossible to discuss them thoroughly here. But in short, the problem with Luther’s position was twofold. Firstly, the Catholic Church in the West had long held that a man in holy orders could not marry, so Luther was directly bucking the authority of a long line of Popes and ecumenical councils which had specifically affirmed this for theological reasons (see “Celibacy and the Priesthood” for a more in-depth discussion of them). The second issue was much broader: when Luther asserted that the Church had no right to prevent a marriage, he was effectively claiming that the supreme authority of the Catholic Church had no control over what constitutes a valid sacrament. Eventually Luther took his thesis to its logical extreme, and denied that marriage is a sacrament at all—a position which Lutherans still hold today.

The Catholic Church’s response to all this is found in Canon 13 on the Sacraments in General, from the 7th Session of the Council of Trent:

If anyone says that the received and approved rites of the Catholic Church, which are accustomed to be used in the solemn administration of the sacraments, may be disregarded, or omitted at the pleasure of the ministers without sin, or changed by every pastor of the churches into other, new ones, let him be anathema.

In other words, it is for the supreme authority of the Catholic Church to decide what constitutes the correct means of conferring/receiving a sacrament—and nobody else on earth has that right! This is, of course, entirely consistent with the Catholic Church’s understanding of papal authority, something which has been discussed many times before in this space (in “Are There Any Limitations on the Power of the Pope?” and “When Does the Pope Speak Infallibly?” among others).

This is why the current canon 841 says what it says.

We can see what the Council Fathers at Trent had to say about anyone embracing David’s theological position. But in his statement above, David isn’t only speaking about the sacraments in general—he’s also specifically referring to the sacrament of marriage. As we have seen so many times before in this space, the Church has established that for a Catholic to marry validly, he/she must observe canonical form (c. 1108). This means that the marriage must be celebrated by the diocesan bishop, the pastor of the parish, or another priest/deacon delegated by either of them; and in the presence of two witnesses.

Once again, the current law on canonical form wasn’t randomly invented in 1983; it too has been with us since the Council of Trent, where it was formulated during the 24th session in 1563. Today the decree mandating canonical form is known as Tametsi, from the first word of the Latin text (also discussed in “Can a Catholic Ever Get Married in a Non-Catholic Church?”).

There were a number of different reasons why the Bishops at the Council established the canonical form for marriage, and they weren’t necessarily Martin Luther’s fault. One big one was the chronic problem the Church had long been having in that era with clandestine marriages. Before Trent, it was possible (although frowned upon) for a bride and groom to exchange consent privately—and the Church accepted this as a valid marriage.

It should be obvious that valid-but-secret Catholic marriages had plenty of potential to create plenty of problems. Imagine that Michael and Elizabeth, both Catholics, exchanged vows privately back in that era in Paris, and so no record of their marriage existed at their parish or anywhere else. Let’s say that Michael now travels to Vienna for work-related reasons, and meets the gorgeous young Maria, whom he finds much more attractive than his wife Elizabeth back home. What would stop him from proposing marriage to Maria? Think about it: nobody in Vienna knows Michael, so they have no idea he already has a wife back in Paris. His Parisian parish has no record of any marriage, so even if the priest in Vienna wants to check up on Michael’s marital status, there’s no reliable way for him to do it! Under such circumstances, Michael could easily commit bigamy, and celebrate a Catholic wedding (invalidly, of course) with the unwitting Maria in Vienna—leaving his real wife Elizabeth back in Paris, wondering why her husband hasn’t returned home yet.

The problems caused by clandestine Catholic marriages had already existed before Luther and the other reformers came along. But when the protestants began to celebrate weddings of their own, and insisted that their own clergy (who were sometimes excommunicated Catholic priests like Luther himself, and other times not ordained Catholic clergy at all) could officiate just like priests in Catholic parishes… the Church realized that its whole method of celebrating weddings needed to be overhauled.

Trent required that marriage banns be published in advance, on three separate occasions (see “Why Doesn’t the Church Publish Marriage Banns Any More?” for more on how banns are published today), “so, if there be any secret impediments,” the Council Fathers declared, “they may be the more easily discovered.” Trent also required that all marriages be celebrated just as is required by canon 1108.1 today—and if they are not, “the holy Synod… declares such contracts invalid and null, as by the present decree it invalidates and annuls them.”

This is why the current canon 1108 says what it says.

Now that we’ve summarized the history behind the Church’s teachings on sacraments in general, and marriage in particular, let’s try as best we can to sort through David’s many erroneous assertions. For starters, as we’ve already seen, the Catholic Church holds that the supreme authority in the Church certainly does have the power to determine the validity of a sacrament; to deny this is to deny the authority of the Pope, just as Martin Luther did.

David also seems somehow to have confused the distinction between sacramental and non-sacramental marriages, and the spouses’ sinfulness. In actual fact, the Church has never held that a person who is in a state of sin cannot celebrate a sacrament; on the contrary, as we saw in “Pedophile Priests and Sacramental Validity,” Catholic theology has held for many centuries that sacraments are effected ex opere operato (literally, “from the work having been worked”), and not ex opere operantis (“from the work of the worker”). Consequently, it is quite absurd to say that “for a marriage to be invalid, there would have to be an absence of Sanctifying Grace, i.e. Mortal Sin.” It is astonishing that someone with a degree in Catholic theology would fail to understand this basic theological principle.

As was discussed at length in “If a Catholic Marries a Non-Christian, How is it a Sacrament?” and “Catholics in Non-Sacramental Marriages,” a non-sacramental marriage is one that involves at least one spouse who is not baptized. That’s because a person must first be baptized, before he/she can receive any of the other sacraments. A marriage that is non-sacramental is certainly not automatically invalid—that’s a totally separate issue—and being in a non-sacramental marriage does not imply that the spouses are in a state of grave sin, either! David’s conflation of these altogether different concepts is extremely difficult to explain.

But in short, his claim that canon law has no authority is not an attack on canon lawyers; it’s a direct assault on the Catholic Church and its supreme authority. As any competent church historian can tell you, canon law in one form or another has been with us since practically the very inception of the Church by Our Lord Himself, in the first century A.D. To suggest that nobody in the Catholic Church has authority over the sacraments is to assert that for the past two millennia, a whole succession of Popes, Bishops, and Ecumenical Councils have systematically been misleading the faithful, by making rules which they have no right to make. It is to assert that the Catholic Church as it is constituted is a fraud.

Martin Luther would be proud.

If David were a non-Catholic, these assertions would be totally understandable. But as it is, it’s truly mind-boggling to think that a Catholic college gave him not only a degree in Catholic theology, but did so with highest honors. You have to wonder what’s going on in the theology department of that college, and whether other graduates leave the program with the same confused, heretical understanding of Catholic teaching that David espouses here.

There are a couple of different take-away’s from all of this. First of all, when Christ instituted His Church, He entrusted one man with supreme authority over it here on earth. The Pope can—and always could!—give the Church guidance on what is necessary to celebrate the sacraments validly.

Secondly, prospective students and their parents should look carefully at Catholic colleges and universities that claim to impart a solid, orthodox Catholic education. It’s great when the atmosphere at a school is imbued with Catholic culture, but as we’ve just seen here, that doesn’t automatically mean that a student will receive sound formation in the Catholic faith. Let’s say a prayer for David and any other students who think they’ve received a real Catholic education, but were somehow led astray.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

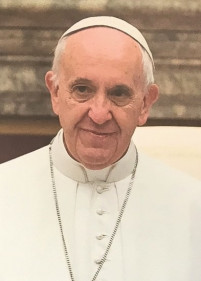

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.