Q: I have heard of something called the “Pauline Privilege.” I gather that, based on Saint Paul’s words in I Corinthians, it means that if I left my wife before I was baptized, she could have been allowed to re-marry? –John

A: Most Catholics have probably never heard of the Pauline Privilege, but it’s an important component of the Church’s law on the indissolubility of marriage. It’s also one of the relatively few instances where specific laws found in the current code are taken directly from Sacred Scripture—in this case, from the words of Saint Paul himself.

The Pauline Privilege constitutes an exception to the Church’s general rules governing marriage, rules which are grounded in sacramental theology. Let’s look first at what the Church teaches in general about dissolving a marriage; and then at what Saint Paul had to say about how to handle a certain specific marital situation.

Canon 1141 couldn’t be more blunt. It asserts that a marriage that is “ratified and consummated” (in Latin, ratum et consummatum) cannot be dissolved by any human power, or by any cause other than death. In other words, a marriage is truly indissoluble if (a) it has been celebrated with a valid marriage rite; and (b) the spouses have subsequently engaged in a “conjugal act, in itself apt for the generation of offspring” (c. 1061.1). If condition (a) is missing or defective in some substantive way, the marriage may be annulled, since it was never properly ratified to begin with (see “Marriage and Annulment” for a more detailed discussion of this). If condition (b) is missing, the marriage is known as “ratum sed non consummatum,” and the Pope has the power to dissolve it (c. 1142). Otherwise, a marriage ends only with the death of one of the spouses.

This is not some modern, “post-Vatican II” formulation of the issue—far from it! The notion that a ratum et consummatum marriage is indissoluble developed in the Catholic Church over the course of the past two millennia, and in fact is originally based on teachings found in the Old Testament (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church 1610-1611 and 1614-1615). Sacramental theologians, canonists, and church historians have, in some cases, dedicated their scholarly careers to tracing the development of this concept. It is a hard-and-fast rule that, as the Church teaches, governs the marriages of non-Catholics too, and it admits of no exceptions.

Except, that is, for a couple of statements found in the New Testament, which directly conflict with everything that was just said about the general indissolubility of marriage! If you’re well versed in Scripture, you might already be familiar with the passage in Saint Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians, which is the basis for the Pauline Privilege that John mentions:

To the married I give charge, not I but the Lord, that the wife should not separate from her husband (but if she does, let her remain single or else be reconciled to her husband), and that the husband should not divorce his wife.

To the rest I say, not the Lord, that if any brother has a wife who is an unbeliever, and she consents to live with him, he should not divorce her. If any woman has a husband who is an unbeliever, and he consents to live with her, she should not divorce him. For the unbelieving husband is consecrated through his wife, and the unbelieving wife is consecrated through her husband…

But if the unbelieving partner desires to separate, let it be so; in such a case the brother or sister is not bound. For God has called us to peace (1 Cor. 7:12-15, emphasis added).

What’s going on here? In this passage, Saint Paul has asserted that in a particular set of circumstances, a ratum et consummatum marriage really can be dissolved. He acknowledges right up front (“I say, not the Lord”) that this isn’t coming from God—rather, it’s coming from Paul himself. According to Paul, the overall indissolubility of marriage has a loophole: if two unbaptized people are married, and one of them is subsequently baptized, the marriage can be ended if the other spouse both (a) remains unbaptized—note that Paul describes him/her as “unbelieving”—and (b) “desires to separate” from his/her spouse.

This statement from Saint Paul constitutes an exception to the otherwise universal norm. The Pauline Privilege permits a ratum et consummatum marriage to be dissolved, in favor of the faith.

In canon law, Saint Paul’s words eventually took on the form found in canon 1143. It states that a marriage entered by two unbaptized persons is dissolved when one of the spouses is baptized, and enters a new marriage, if the unbaptized spouse departs. There are a number of criteria, all of which must be present, for this privilege to apply.

Firstly, the Pauline Privilege is only relevant if one of the spouses becomes a Christian and the other does not. In other words, if both spouses are baptized after their marriage, and they then want to separate and remarry, they cannot do so under canon 1143.

Secondly, the privilege can be applied if the unbaptized spouse is either unwilling to continue living with the newly baptized spouse, or if the unbaptized spouse is not willing to do so without “offense to the Creator.” In other words, if the unbaptized spouse is so antagonistic toward the Christian faith of the newly baptized husband or wife that they cannot live together in peace, this constitutes “departing” for the purposes of canon 1143.

(Note that the Pauline Privilege cannot be used if it is the baptized spouse who “departs.” So long as the unbaptized spouse is willing to remain in the marriage, and is not hostile to the Christian faith of the other spouse, the marriage cannot be dissolved other than by death, as per canon 1141.)

Thirdly, the newly baptized spouse must want to enter into a new marriage. Unless and until this happens, he/she remains married to the unbaptized spouse.

The application of the Pauline Privilege doesn’t constitute an annulment of the original marriage, as the marriage of the two unbaptized persons is presumed to be valid. Thus there is no need for the newly baptized spouse to go through the usual annulment process if he/she wants to remarry. Instead, what is necessary is a finding by the Church that the conditions required for application of the Pauline Privilege are all in place in this particular situation. Canon 1144 mandates that the unbaptized spouse must be questioned, to determine whether he/she wishes to be baptized too, and if not, whether he/she is in fact willing to continue living peacefully with the newly baptized spouse, “without offense to the Creator.” If it is established that all the conditions for the Pauline Privilege are met, the first marriage is dissolved, ipso facto, when the baptized spouse remarries.

As we can see, this is a very specific situation that doesn’t happen extremely often, except possibly in missionary countries with significant numbers of non-Christians constantly converting to the faith. It’s true, favor-of-the-faith cases occur sometimes even in countries which were Christianized many centuries ago, but they nevertheless constitute a small percentage of remarriages among Catholics. In the vast majority of cases, as we’ve just seen, a marriage is indissoluble if it was celebrated validly (which therefore means it cannot be annulled) and has been consummated by the spouses.

We’ll never know for sure, but it seems likely that if Paul had never written these words, the Catholic Church would never have permitted this exception to its teaching on the indissolubility of marriage. Saint Paul wasn’t a canon lawyer, of course, but the Code of Canon Law defers to him all the same.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

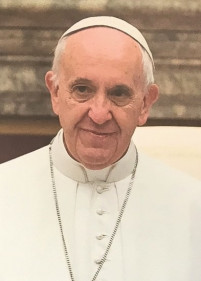

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.