Q: What, if anything, does canon law say about fasting before receiving Holy Communion? It used to be that you had to fast since midnight of the night before; then it was three hours before, then one hour before, and now some Catholic friends tell me you don’t have to fast any more at all. Others tell me that you do, but coffee and tea don’t count. Who’s right? –Anna

A: Anna is right that the rules on fasting before receiving the Eucharist have changed in the past several decades or so. While the changes were meant to make it easier for Catholics to receive Holy Communion, the sad fact is that even the less strict, current requirements are frequently disregarded altogether. And many Catholics don’t even know that the Eucharistic fast even exists! Let’s look briefly at the changes that have been made in the law on this subject over the years, and then we can more easily understand and appreciate the law on fasting before receiving Holy Communion today.

From time immemorial, Christians fasted before receiving the Eucharist. It appears that a requirement to fast from food and drink was in effect already as long ago as the 3rd century: the Christian writer Tertullian, who died about 240 A.D., described the Eucharist as the bread which Christians ate before taking any other food (Ad uxorem II.5). This shouldn’t be surprising; Jewish religious customs frequently involve fasting, so the early Christian community likely embraced the concept as a matter of course.

For centuries, Catholics were required to fast from all food and drink—including water!—from midnight of the evening before receiving Holy Communion. If you went to bed early, and then attended an early morning Mass, this fast wasn’t necessarily difficult. But for many people in other situations, it could be rigorous almost to the point of cruelty. Sick, feverish people who needed to drink water frequently would sometimes find the fast almost impossible to keep (St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, who lived in the United States in the 18th-19th centuries, experienced this trial when she was very ill herself). Travelers, arriving late to their home or hotel on a Saturday night, might realize that by the time they could get some dinner it would be after midnight—so they had to choose between going to bed without having eaten for many hours, or foregoing Holy Communion the next morning. And people who worked night-hours, like policemen or hospital staff, would at times be obliged to work for many hours straight, without eating or drinking anything to keep up their strength.

This requirement applied to priests who celebrated the Mass too. Once again, if a priest went to bed early, said a daily Mass at 7 AM, and had breakfast right after that, the obligation to fast since the preceding midnight might not be taxing at all. But imagine how difficult it could be for a missionary priest, who travelled for hours (sometimes on foot!) before celebrating Mass in some rural village; or even for an ordinary parish priest who said three Masses on Sunday morning, sometimes unable to eat or drink anything until long after noon.

The 1917 Code of Canon Law reflected this traditionally strict Eucharistic fast. The former canon 858.1 provided only two exceptions to the rule that one had to fast from the preceding midnight: danger of death, and cases when there is need to prevent desecration of the Blessed Sacrament. A good, though fictional, example of this latter exception can be seen in the 1963 film The Cardinal, when the Catholic clergy race to the bishop’s private chapel and consume the Hosts reserved in the tabernacle, before Nazi soldiers can break the door down and desecrate the place. The need to protect the Eucharist from such outrages naturally outweighed the obligation of the Eucharistic fast.

Speaking of clergy, the 1917 code was quite blunt about their need to fast before celebrating Mass: the former canon 808 noted simply that a priest could not licitly celebrate the Mass unless he had fasted since midnight. Note that a priest can always celebrate a Mass that is valid; as we saw in “Can a Bishop Forbid a Priest to Say Mass?” once a man has been ordained a priest, he always retains the power to consecrate bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ. But this canon of the 1917 code observed that if he failed to fast since the preceding midnight, such a priest would celebrate Mass illicitly, meaning that his action was illegal. (See “Are They Really Catholic? Part II” and “Why is This Method of Baptizing Illicit?” for more on the distinction between validity and liceity.)

The 1917 code did, however, make a slight concession to sick people who wanted to receive Holy Communion. The former canon 858.2 stated that those who are ill for a month, and have no reason to expect a speedy recovery, can, with the approval of a prudent confessor, receive the Eucharist sometimes even if they have taken medicine or something to drink beforehand.

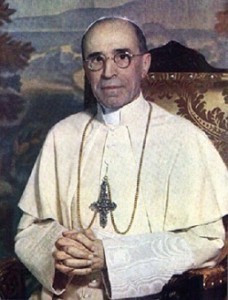

Note that under the former code, even medicine was considered to break the Eucharistic  fast! But that changed in 1953, when Pope Pius XII rewrote the rules so that taking water and medicine did not count. This was a big step forward in reforming the law on fasting before Holy Communion. Many people who previously would have been unable to receive the Eucharist (think of young children and pregnant women who really needed a drink of water!) could now do so.

fast! But that changed in 1953, when Pope Pius XII rewrote the rules so that taking water and medicine did not count. This was a big step forward in reforming the law on fasting before Holy Communion. Many people who previously would have been unable to receive the Eucharist (think of young children and pregnant women who really needed a drink of water!) could now do so.

A few years later, Pius XII changed the law even more radically, reducing the time-period of the fast. Instead of fasting from midnight of the preceding night, all those who wanted to receive the Eucharist now needed to fast for only three hours in advance. In addition, Pope Pius’s new rules allowed that sick people (including sick priests who wanted to celebrate Mass) were permitted to drink something—not necessarily water—before receiving Communion.

In 1964, Pope Paul VI took it even further. The three-hour fast was further reduced to only one hour. And Paul VI also allowed diocesan bishops to relax the rules for their priests who were obliged to celebrate two or even three Masses on the same day: with the bishop’s approval, these priests could take something to drink (not just water) between Masses, even less than one hour in advance.

The law was relaxed even further for sick persons in 1973, when the Sacred Congregation of the Sacraments (today the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments) issued an instruction with the approval of Paul VI. Now sick persons (including sick priests), elderly people who were homebound or in nursing homes, and those who cared for them, needed only to fast for 15 minutes before receiving the Eucharist. We can see that the reality of the practical difficulty often involved in long fasts for such persons was understood and acknowledged.

With the promulgation of the current Code of Canon Law in 1983, Pope John Paul II gave us the current law, found in canon 919. The first paragraph lays out the norm: whoever is to receive the Eucharist is to fast for at least one hour before Communion from all food and drink, with the sole exception of water and medicine (c. 919.1). The phrase “at least one hour” indicates that this is the bare minimum, and devotion to Our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament may of course prompt us to fast for an even longer period if we choose to do so. And note that the canon specifies “one hour before Communion,” not one hour before the Mass begins.

While the law doesn’t mention it, the medicine it refers to doesn’t need to be a prescription; aspirin, cough syrup and other over-the-counter medications can be taken too.

The one-hour fast applies to priests as well, but those priests who celebrate Mass two or three times may take something—food or drink—before the second or third Mass, even when the interval between Masses is less than an hour (c. 919.2). And sick and elderly persons, as well as those who care for them, may receive Holy Communion even if they have taken food or drink within the preceding hour—meaning in practice that they don’t really need to fast at all (c. 919.3).

What a difference from the law that was in force only a century ago! By now it should be clear that the Church gradually changed its traditional rules to accommodate Catholics in the various sorts of circumstances that made following the earlier law so difficult. The Church is balancing the need to approach Holy Communion with reverence, with the desire to allow its members to receive Communion even in difficult physical circumstances. In particularly unusual situations, the diocesan bishop can dispense from canon 919 altogether if he deems fit (see “Marriage Between a Catholic and a Non-Catholic” for more on what a dispensation is).

Since the law today is so lenient, and so easy for the vast majority of Catholics around the world to follow, there’s really no excuse not to follow it. It’s bewildering to encounter so many Catholics in first-world countries, for example, who think that drinking black coffee or tea doesn’t violate the Eucharistic fast—because it certainly does. It could be that these Catholics are mentally equating fasting and dieting, and they wrongly conclude that since coffee and tea have no calories, they are the equivalent of water. This idea would probably shock Catholics in many other parts of the world, where coffee/tea is an expensive luxury! Your coffee or tea may be cheap and contain no sugar or cream, but that does not mean you can drink it less than an hour before receiving the Eucharist, unless you fit into one of the categories mentioned in the second or third paragraph of canon 919.

So now Anna has the complete answer to her question, with some historical context thrown in for good measure. The indescribable spiritual benefits derived from our reception of Christ in the Eucharist are certainly worth a brief fast from food or drink! And while the law has become very lenient and easy to follow, it is still a law that Catholics must obey.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.