Q: Did you hear about the man caught masquerading as a priest in Los Angeles? I never thought about it before, but now I’m wondering why this doesn’t happen more often…. What is a pastor expected to do when a man claiming to be a priest wants to use the church to say Mass, or offers to help out at the parish in other ways? –Shannon

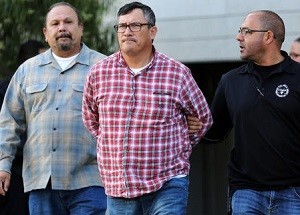

A: Shannon is of course referring to Erwin Mena, a layman who somehow managed  repeatedly to convince both clergy and parishioners of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, California, that he was a bona-fide Catholic priest. After engaging in faux priestly ministry for some time, including celebrating Mass and administering the sacraments, it was established that he is nothing more than a con-artist, pretending to be a priest while stealing thousands of dollars from parishioners. Mena is now under arrest for grand theft, among other things.

repeatedly to convince both clergy and parishioners of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, California, that he was a bona-fide Catholic priest. After engaging in faux priestly ministry for some time, including celebrating Mass and administering the sacraments, it was established that he is nothing more than a con-artist, pretending to be a priest while stealing thousands of dollars from parishioners. Mena is now under arrest for grand theft, among other things.

How could this have happened? What should have happened in this case and didn’t?

Before pointing any fingers, it’s important to remember that the full story has not been aired in the press (at least, not yet). Presumably the clergy and laity involved are sharing what they know with law-enforcement authorities, and more details may come out during Mena’s criminal trial. But it’s nonetheless possible to discuss the Church’s rules about how the clergy of one diocese are to deal with priests who visit from another and offer/ask to celebrate Mass and the sacraments—because general rules definitely exist. Let’s take a look first at the Church’s standard operating procedure in these matters, and then at the specific California case which Shannon mentions.

Canon 903 explains how these situations are supposed to work. A priest who is not known to the rector of a church is to be permitted to celebrate Mass there, if (a) he presents a commendatory letter no more than one year old from his own superior, or (b) it can be prudently judged that he is not debarred from celebrating Mass. There are several different conditions mentioned here, so let’s examine this canon piece by piece.

First of all, if a visiting priest shows up at a church (whether it’s a parish or not is irrelevant, see “Is Every Catholic Church a Parish?” for more on this), and is already known to the pastor or other priest in charge, canon 903 does not even apply. If the priest in charge discovers that the visitor is his former seminary classmate, or recognizes him as a priest who is frequently seen on a Catholic television program, the visitor is “known” to be a priest. So strictly speaking, there’s no particular reason under this canon to demand additional proof the man is a bona-fide priest. The priest in charge may, therefore, permit him to celebrate Mass immediately, with no conditions attached.

The situation is different, of course, if a visiting priest knocks on the door of a church and the priest in charge has absolutely no idea who he is. How can he tell whether the visitor is really a priest in good standing, or one who’s been suspended and forbidden to celebrate the sacraments, or merely a poor soul suffering from delusions—or even worse, some sort of con-artist? As canon 903 notes, a genuine priest should be able to present a “commendatory letter,” from his bishop (if he’s a diocesan priest) or his religious superior (if he’s a member of a religious institute). This is sometimes translated somewhat awkwardly into English as a “letter of suitability.” A sort of clerical ID-card also exists, traditionally known as a celebret, from the Latin word meaning “let him celebrate,” or “he may celebrate.” The letter or the celebret proves that the man claiming to be a priest is the real deal.

But canon 903 asserts that presentation of the letter or celebret is not always necessary, because often common sense works just as well. Let’s imagine another scenario now, in which a long-time parishioner, who is well known to the pastor of her parish, tells him that her cousin will be visiting for two weeks this summer. The visiting cousin is a retired Jesuit priest, and during his stay he would like to say Mass at his cousin’s parish. What should the pastor do?

Well, if he knows that this parishioner is a basically honest person, of sound mind, there’s no logical reason to worry that perhaps she’s deceiving him about her cousin’s identity. Let’s say that the visiting cousin finally arrives and is introduced to the pastor, and tells him which Jesuit province he’s from and where he used to minister before his retirement—and it all makes perfect sense. Circumstances such as these would fit neatly into canon 903’s provision that the pastor may prudently judge that the man is not debarred from saying Mass. Thus the pastor wouldn’t have to demand that the retired Jesuit produce a celebret—in fact, insisting on it might conceivably come across as unreasonable overkill.

Situations like this one happen all the time, which is why using common sense is often just as effective as any celebret—and is just as acceptable under canon law. If a strange man shows up at a church, identifies himself as a priest from a particular diocese or religious institute who is engaged in this or that type of ministry, and he plainly knows all the practical in’s and out’s of celebrating Mass in a church—putting on his vestments correctly, for example, or flipping to the right pages in the Missal—then why would anybody feel the need to question his identity? Ordinarily, one genuine priest can quickly sense the authenticity of another; and the opposite is equally true, as a fraudster being questioned by a real priest will, as a rule, be tripped up pretty quickly. (For that matter, the same thing can be said of two doctors, two electricians, or two canon lawyers: normally they can engage in professional conversation and instantly appreciate each other’s genuineness.)

This common-sense approach explains why in some parts of the world, it’s easy to come across legitimate priests who have never even had a celebret, because in all their travels there has never been any real need for one. The “prudent judgment” of the priests in charge of any churches they may visit is normally sufficient for them to obtain permission to say Mass there. So if a man claims to be a priest but can’t produce a celebret, this does not automatically mean that he’s a fake!

But before concluding that every pastor around the world has the right to make his own judgment-calls under canon 903, there’s another important factor to consider. There are many dioceses whose bishops have implemented specific policies on how to apply canon 903—so in obedience to their lawful superior, priests of these dioceses are of course required to comply. Sometimes these dioceses are, by their very nature, filled with visiting clergy who are not known to the priests of the diocese—perhaps there’s a huge pontifical university located within diocesan territory, and many foreign priests come to study there; or the diocese may contain a huge basilica where large groups of pilgrims from around the world routinely show up under the leadership of a priest from their parish. Alternately, if a diocese has had a bad experience with imposter-priests in the past, a bishop might naturally want to be extra-careful that it never happens again! A bishop can, for example, mandate that all unknown priests who wish to celebrate Mass in a church in the diocese must first provide a current celebret or a letter of suitability. This is an entirely legitimate way to handle these situations, consistent with canon 903.

Now let’s see how all this applies to the strange situation of the priest-impersonator Erwin Mena, who deceived so many people in California. It appears that Mena had been identified as a fraud before, since his name was already included on a list distributed by the Los Angeles Archdiocese to all its clergy. The men on the list are not priests in good standing (they might be under suspension, for example), or they are members of schismatic groups not in communion with the Catholic Church (several on the list are identified as belonging to the Old Catholic Church, which split from Rome after the First Vatican Council in the 1800’s), or they might not even be priests at all.

It would seem that at a minimum, priests of the Archdiocese are required to check the list when an unknown priest appears on the scene—and in this case somebody failed to do so. In January 2015, Mena showed up at St. Ignatius Church in L.A., when the pastor was going on vacation and needed a substitute—and by saying/doing all the things a real priest would say/do, Mena convinced not only the pastor, but the entire parish that he was a genuine priest—without ever providing a celebret or letter of suitability. Since he is said to have studied in a Central American seminary in decades past, Mena probably learned there all that was needed to pass himself off as a priest. St. Ignatius was clearly not the first Los Angeles parish to be snookered by Mena: his name ended up on the watch-list because over the years he had managed to trick numerous other clergy and laity in the Archdiocese too.

During his most recent “ministry,” Mena is said to have celebrated not only the Mass (which obviously was invalid, cf. c. 900.1), but also the sacraments of baptism, reconciliation, and matrimony. The baptism(s) performed by Mena could very well be valid, since (as we have seen many times before in this space) anybody can baptize provided that he has the intention to do what the Church intends (cf. c. 861.2). But as a non-priest, he was utterly unable to absolve penitents of their sins in the confessional (c. 965), and any wedding he performed is unquestionably invalid due to lack of canonical form (c. 1108; see “Does a Catholic Wedding Have to be Held in a Catholic Church?” and “Why Would a Wedding in Our College Chapel be Invalid?” for more on what canonical form is).

If the pastor of the parish where Mena substituted was required by diocesan protocols to insist on seeing a letter of suitability or a celebret, it looks like those protocols were not followed, because Mena had none. But if perhaps Mena had come to St. Ignatius claiming that he had previously ministered in another L.A. parish, and the pastor of St. Ignatius established that Mena had indeed done that… well, one can see how this sad deception might have occurred.

Mena has been removed, but the issue of the invalid sacraments he celebrated must be addressed (and there’s no doubt that the clergy of Los Angeles are doing just that). Any wedding(s) at which Mena officiated have to be re-celebrated, by either the parish priest or another authentic cleric authorized to do so. If Mena invalidly celebrated Mass for an intention for which someone had given a stipend, a Mass for that intention must be re-scheduled and celebrated correctly (cf. cc. 949 ff.; also see “Mass Intentions and Stipends” for more on this). If he “consecrated” hosts which were known to be in the parish tabernacle, the pastor has most certainly already removed them, although God only knows how many unconsecrated hosts were unwittingly received by the parish faithful in Holy Communion during Mena’s stay at St. Ignatius.

The invalid confessions are more complicated to remedy: technically, we are obliged to confess all grave (mortal) sins, while confessing venial sins is recommended but not actually required (c. 988). Anyone who confessed a mortal sin to “Father” Mena didn’t receive absolution—although of course this is not the penitent’s fault! Perhaps the safest bet might be for anyone who knows he confessed grave sins to Mena to explain this in another confession to a genuine priest, and confess them again if the priest thinks it appropriate. In such a sticky situation it’s important for penitents to defer to their priest-confessor’s judgment. At the same time, maybe there are some penitents out there who passed through Los Angeles, confessed to Mena without knowing who he was, and then went on their way. They may thus be unaware of the problem, again through no fault of their own—and the question of such confessions as these is best left in the Hands of God.

The Church is fortunate that very few priest-impersonators are such convincing liars as Erwin Mena appears to be! This tragic event has highlighted the need for priests worldwide to be careful about automatically assuming that a visiting priest is who he says he is. And if both canon law and (where applicable) local diocesan rules are followed, fake priests normally will be spotted and quickly stopped, before doing damage to the spiritual wellbeing of the faithful.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.