Q: Aren’t priests forbidden to hold political office? I thought they were, but then I read that the government of Libya nominated a Catholic priest to be their Ambassador to the United Nations! How is a priest allowed to hold a job like that? –Nick

A: Nick’s confusion is entirely justified. Unfortunately, what some Catholic priests in various parts of the world have chosen to do in recent years is not necessarily in synch with current canon law.

Canon 285.3 states that clerics are forbidden to hold public office whenever it means sharing in the exercise of civil power. The Church has interpreted the phrase “sharing in the exercise of civil power” to refer to those political positions which involve legislative, executive, and judicial power. This in turn means that becoming a member of Congress or Parliament, a cabinet official, or a judge are all off-limits to Catholic clergy.

We can get a pretty clear idea of why the Church forbids its clergy to engage in this type of work when we look at canon 285 as a whole. Its first paragraph asserts that clerics are completely to shun everything that is unbecoming to their state; and if that’s not unambiguous enough, the next paragraph states that the Catholic clergy are to avoid activity that it foreign to their state, “even if it is not unseemly.” In other words, some jobs—say, working as a gynecologist—are normally considered inappropriate work for a Catholic cleric, so such activity would be banned by canon 285.1. Other work—like repairing cars, or running a dry-cleaner’s—is certainly harmless in and of itself, but canon 285.2 would still forbid Catholic clergy to engage in it, simply because it is not suitable work for them. A man who is dedicated to God is expected to live accordingly!

It’s the very next paragraph of this same canon that addresses clergy holding political office, so the implication is plain: even though there is nothing intrinsically wrong with working in politics, it nevertheless is not appropriate work for Catholic clerics.

Note that as a rule, permanent deacons are “clerics,” and thus they are ordinarily included in canons pertaining to the clergy—but this time we’ve got an exception. Canon 288 specifically states that permanent deacons are not bound by the prohibition found in canon 285.3. That means that permanent deacons can legitimately be elected to public office.

So why is it that from time to time, we encounter stories of Catholic priests serving in public office? Well, one reason is that the canons we just looked at have not always been in force. As was discussed in “Are Women Required to Cover Their Heads in Church?” the current Code of Canon Law was promulgated by Pope John Paul II in 1983, less than 30 years ago. It replaced the code that had been promulgated by Pope Benedict XV, back in 1917. And the equivalent canon in the previous code, which was in force from 1918 to 1983, contained a sort of loophole.

The corresponding canons in the 1917 code made the same general assertions about the need for Catholic clerics to avoid activities that are considered unsuitable for them, and even provided some detailed examples. They specified that the clergy shouldn’t go hunting, or even enter a tavern without just cause, practice medicine without their superiors’ approval, or work as lawyers in civil courts. As for holding public office, the former code noted that as a rule, the clergy were not to seek or accept such a role without the permission of both their own bishop (or, in the case of clerics who were members of religious institutes, their religious superior), and the bishop of the territory in which the election was being held.

Keep in mind that the world was a different place back in 1917, and the Church at that time foresaw instances in which a priest might reasonably be allowed to work as an elected official in some countries. Back then, numerous countries had laws declaring that Catholicism was the official state religion, and so the relationship between the civil government and the Catholic Church in these nations was very different from the one that we Americans are accustomed to today.

The 1917 code was still in effect when Jesuit Father Robert Drinan, for example, was first elected to the US Congress in 1971, as a Representative from Massachusetts. The understanding at the time was that Fr. Drinan had obtained permission from his Jesuit Superiors to engage in politics—something which was technically possible under the old code. (For the record, it subsequently came to light that he had not in fact obtained the requisite approval after all.) Fr. Drinan’s voting record became a matter of great scandal when he repeatedly voted in favor of abortion, while claiming at the same time to be “personally opposed”—a fact which did not escape the attention of the new Pope, John Paul II. He’d been elected Pope while Fr. Drinan was still a member of Congress.

When the Pope announced publicly in 1980 that priests would henceforth not be permitted to hold political office, he was foreshadowing the change that would soon be articulated in the new Code of Canon Law. It was only at that point that Fr. Drinan left the House of Representatives, as he did not seek re-election that year. To this day, the Drinan case constitutes a good example of the potential harm that can be done when Catholic clergy become unduly involved in contemporary civil politics. The controversial voting-record of Congressman Drinan, and the understandable scandal it was causing, might very well have been the motivating factor behind John Paul II’s decision to revamp canon law on this issue.

There is, however, a different reason why we sometimes hear about priests in various countries around the world becoming involved in politics nowadays: sadly, some Catholic clerics simply choose to violate canon law. The priest whom Nick mentions in his question is a case in point.

Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann is—note the present tense!—a Maryknoll priest who was born in the United States, but was later sent by his religious superiors to work in Nicaragua. In the 1970’s, he became deeply involved in the political struggle there that culminated in the rise to power of the leftist Daniel Ortega. Fr. d’Escoto became the Foreign Minister (equivalent to a Secretary of State) in Nicaragua’s new, communist-allied Sandinista government in 1979.

He wasn’t the only Catholic priest to whom Ortega gave such a high political position, either: Jesuit Father Fernando Cardenal became Nicaragua’s Minister of Education, while his biological brother, Franciscan Father Ernesto Cardenal, was tapped to be the new Minister of Culture. None of these priests had received approval from their superiors to accept these political positions, as was required under the 1917 code (which at that time, remember, was still in force). They were all, therefore, in blatant violation of church law.

When John Paul’s ban on clergy holding political office was announced the following year, all of these priests were effectively being told to choose: either leave politics, or leave the priesthood. (The laicization of priests was discussed in detail in “Can a Priest Ever Return to the Lay State?”) While Fr. Drinan, to his credit, responded by renouncing politics, the three clerics in Nicaragua did not respond at all, choosing rather to ignore the Pope’s directive completely.

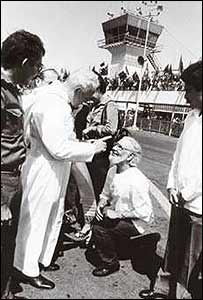

Readers who are old enough to remember Pope John Paul II’s trip to Nicaragua in 1983 may recall the image, broadcast on the nightly news and published in the papers, of the  Pope wagging his finger angrily at a kneeling Ernesto Cardenal. Speaking in Spanish, the Pope admonished him openly, “You must regularize your condition in the Church!” But Fr. Ernesto never did, and was suspended from the priesthood as a result. (The implications of a priest’s suspension from active ministry were discussed in “Are They Really Catholic? Part II.”)

Pope wagging his finger angrily at a kneeling Ernesto Cardenal. Speaking in Spanish, the Pope admonished him openly, “You must regularize your condition in the Church!” But Fr. Ernesto never did, and was suspended from the priesthood as a result. (The implications of a priest’s suspension from active ministry were discussed in “Are They Really Catholic? Part II.”)

His Jesuit brother Fernando likewise made no attempt to follow the Pope’s directive, and was eventually booted out of the Jesuit order completely. In this case, however, Fr. Fernando Cardenal later repudiated the Sandinistas, and obtained reinstatement as a Jesuit. Having left politics altogether, he is ministering as a Jesuit priest today.

The third priest in the Nicaraguan government, Fr. Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann, is still involved in leftist politics to this very day. Suspended from priestly ministry, he is still referred to sometimes as “Father” by the United Nations, which elected him President of the UN General Assembly for 2008-2009. In a decidedly unusual twist, d’Escoto Brockmann was later nominated by Libyan dictator Muammur Gaddafi to become Libya’s representative to the United Nations. Because Libya’s original nominee could not obtain the US visa necessary to come to New York City (where the UN is located), the Libyan government turned to a non-Libyan who could.

With Gaddafi’s death and the consequent political upheaval in Libya today, the fate of d’Escoto Brockmann’s nomination is naturally unclear—but what we do know is that he remains a Catholic priest under the sanction of suspension, because apparently he has never attempted to straighten out his canonical status within the Church. In accord with canon law, d’Escoto Brockmann could request laicization, thereby losing the clerical state (as discussed in “Can a Priest Ever Return to the Lay State?”); or he could of course renounce his political activity and seek to return to the Church as a priest in ministry, by requesting the lifting of his suspension. The fact is that he has done neither.

Sadly, this phenomenon is not confined to Nicaragua. There are other priests in various parts in the world today who have chosen to ignore the Church’s directive and have become actively involved in politics. (Until only a few months ago, Paraguay was actually being ruled by a suspended Catholic bishop!) Some of them have decided that political activity is preferable to the priesthood, and have requested laicization; others have ignored the need to make any decision at all, and have been sanctioned by the Church as a result. The one thing they all have in common, though, is that none of them attained political office and still remained a Catholic priest in good standing—because as we’ve seen, that would be canonically impossible. Being a politician, and being a priest, are fundamentally incompatible.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.