Q1: I find the topic of Eastern Catholic Churches very interesting. So I was wondering, is it possible for a Roman Catholic to become, say, Greek Catholic or Coptic Catholic, and if so, how does that work? –Angelo

Q2: My girlfriend is Russian and converted to Catholicism last summer. First question: while converted in a Latin Parish, she is still a Russian Catholic canonically, correct?

Second: We want to get married. Since I am Latin, can my Latin priest marry us? Does she “automatically” switch Rites when marrying me, or does she remain Russian? Can she and I marry in the Russian Rite even though I’m Latin? –Matthew

A: As we saw in “Are They Really Catholic? Part I,” not all Catholics are Roman (or Latin) Catholics. There exists a sizable minority of Catholics around the world—originating generally from regions of the world east of Rome—who acknowledge the Pope as the head of the Church, but whose liturgical rituals and other traditions are often very different from those found in the Latin Church. In most cases, these eastern Catholic groupings were formed when portions of the Orthodox Churches, who have been in schism since the year 1054 (see “Can a Catholic Ever Attend an Orthodox Liturgy Instead of Sunday Mass?” for more on this), returned to communion with Rome. In technical parlance, these groupings are known as Catholic Churches sui iuris. They are truly Catholic, as they share the same faith, same sacraments, and same governance (cf. c. 205) as the Latin Catholics who constitute the vast majority of the Catholic Church; but as their liturgical traditions developed over the centuries in different cultural settings, they can be markedly unlike those which developed in the Latin Catholic Church in the West.

Because we are all Catholics, there is absolutely no reason why, for example, a Latin Catholic can’t attend Sunday Mass (called “divine liturgy”) in an eastern Catholic parish church, such as a Maronite or a Ukrainian Catholic parish. The opposite is of course true as well: many thousands of eastern Catholics, who live in western countries where practically all the Catholic churches are Latin, routinely attend Mass and receive the sacraments from Latin Catholic priests.

But as we saw in “Why Don’t We Marry Validly Before a Ukrainian Catholic Priest? (Eastern Churches, Part I),” the mere fact that a Catholic regularly practices his faith at a parish of a particular Catholic Church sui iuris does not automatically make him a member of that Church (c. 112.2). If you were baptized Catholic as a child, you are in fact a member of your parents’ Catholic Church sui iuris (c. 111.1), whether you know it or not! If one parent is a Latin Catholic, and the other is (for example) a Chaldean Catholic from Iraq, the child will be a member of the father’s Church sui iuris, unless both parents agree that their baby will be a member of the Church sui iuris of the mother.

(Are you confused yet? This is actually a simplified summary of the laws on this topic, which were not invented by Rome. This complicated system was brought into the Catholic Church by the eastern Churches themselves.)

So if we turn now to Angelo’s question, we can see that he not simply asking if a Latin Catholic can attend Mass and receive the Eucharist at a Greek or Coptic Catholic parish’s divine liturgy on Sundays. As we’ve just seen, any Catholic is permitted to do that at any time. Rather, Angelo is talking about something far more permanent: leaving one Catholic Church sui iuris and joining another. Can Catholics do that? And why would they want to?

First of all, yes, a Catholic certainly can become a member of a different Catholic Church sui iuris. There are a couple of different ways to do this, depending on one’s personal situation, and they are found in canon 112.1. A Catholic can ask Rome for permission to change one’s Church sui iuris (c. 112.1 n.1), and the change is effected if/when the permission is received. Note that a diocesan bishop does not have authority to do this for his subjects—because the request by definition involves two different Churches sui iuris, and a bishop of course governs the faithful of only one of them.

There is a less cumbersome way to change Churches sui iuris, if the Catholic wants to become a member of the same Church as his/her Catholic spouse. Let’s say that Paul is a Greek Melkite Catholic, and he marries Elizabeth, a Latin Catholic. There is absolutely no reason why either of them would have to switch, but let’s imagine that Elizabeth feels it’s easier for their new family if she becomes a Greek Melkite Catholic too. Perhaps they regularly attend a Greek Melkite parish anyway, and in Elizabeth’s view it will be simpler for everyone this way. In this case, Elizabeth doesn’t need to request the transfer; she can simply declare that henceforth, she is going to be a Greek Melkite Catholic like her husband. And in future, if Paul passes away before she does, Elizabeth will be free, if she so chooses, to return to the Latin Catholic Church again (cf. c. 112.1 n. 2).

The law also provides for the children of those adults who change Churches sui iuris, in canon 112.1 n. 3. Briefly, if Catholic parents switch from one Catholic Church sui iuris to another, their children under the age of 14 switch too, regardless of how they might feel about it—but when they reach the age of 14, they are free to return to their original Church sui iuris if they want to. We can see here a concrete application of the Church’s basic position that children who are old enough to understand can often make their own spiritual choices, even if they are still young enough to depend on their parents in the material sense (see “Canon Law and Non-Infant Baptism” for more on this general subject).

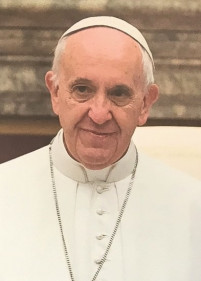

How does this work in actual practice? For many years this was less than clear, but with his 2016 Apostolic Letter De Concordia Inter Codices, Pope Francis added a new paragraph to canon 112 in order to clarify the process. The new canon 112.3 tells us that every transfer of a Catholic from one Church sui iuris to another takes effect from the moment when the Catholic makes a declaration to that effect in the presence of (a) the bishop, or the pastor of the parish, or another cleric delegated by either of them, and (b) two witnesses. The canon adds that the transfer is to be noted in the baptismal registry. (For the record, the changes to the code which were brought about by this Apostolic Letter are nearly two years old, but for unknown reasons they have yet to show up in the text of the Code of Canon Law found on the Vatican’s website.)

So now we have the answer to Angelo’s question. It might be worth noting at this point that if a Catholic petitions Rome to transfer to a different Church sui iuris, he should be absolutely sure that this is what he wants for the rest of his life—because in practice, there’s no going back. As can be imagined, Rome is not generally amenable to capricious Catholics who decide that they want to change Churches, and later change their minds again. This is not a game, and so these requests should not be taken lightly.

Let’s look now at Matthew’s question. The fact that we Catholics are all members of one Church sui iuris or another has potential to create a lot of confusion when it comes to marriage, as we saw in the tragic case discussed in the abovementioned “Why Don’t We Marry Validly Before a Ukrainian Catholic Priest? (Eastern Churches, Part I).” That’s because the Catholic faithful are required to marry before a Catholic cleric of their own Church sui iuris (cf. c. 1109). Thus the two Latin Catholics in that article, whose wedding had been celebrated by a Ukrainian Catholic priest, had been married invalidly—because they were legally required to marry before a cleric of the Latin Catholic Church.

But what happens when, as in Matthew’s case, the spouses are both Catholic, but each belongs to a different Church sui iuris? Let’s go through the various questions which Matthew poses.

First of all, it is correct that if a member of the Russian Orthodox Church becomes a Catholic, he/she becomes a member of the Russian Catholic Church. Matthew’s fiancée might have been received into the Catholic Church in a Latin Catholic parish church, but this does not alter the fact that she automatically becomes a member of the Church sui iuris that corresponds to her Orthodox Church membership.

Where can/should they get married? Canon 1109 (already mentioned above) tells us that the Latin Catholic clergy assist validly at the marriages of Catholics, provided that at least one of them is a Latin Catholic. Since Matthew is a Latin Catholic, they can marry in his parish with no problem at all. Technically, they could likewise be married by a Russian Catholic priest in a Russian Catholic parish, for exactly the same reason; but since there are only a handful of Russian Catholic parishes in the whole world nowadays, the odds that they can even find one are rather slim!

As we have already seen, when Catholics from two different Catholic Churches sui iuris get married, there is no need for either of them to switch Churches—but one of them can transfer to the Catholic Church sui iuris of the other if he/she wishes to do so.

It’s worth noting at this point that Matthew is describing the different Churches sui iuris as “rites,” but this is technically incorrect. As was discussed in “Adopting Children of Another Faith (Eastern Churches, Part II),” the term “rite” refers to the liturgical tradition that a Church sui iuris uses—and in come cases, there are multiple Churches sui iuris which use the same rite. For example, Ukrainian Catholics, Russian Catholics, Ruthenian Catholics, and Romanian Catholics all use the Byzantine liturgical rite! This is an extremely common verbal slip-up, especially in the West: in fact, even the 1983 Code of Canon Law wrongly used the term “rite” instead of “Church sui iuris” in several of its canons, until this error was corrected only recently by Pope Francis’ De Concordia Inter Codices, mentioned above.

If readers’ heads are aching at this point, that’s understandable! It might be difficult to find a canonist who doesn’t wish that the Church’s complex rules about Churches sui iuris were made much simpler and easier to follow. And many, many Catholics—whether eastern or not—have expressed frustration over the years, regarding the seemingly pointless bureaucracy that’s necessarily involved when they’re required by canon 112 to send a petition to Rome and wait for approval (which, by the way, is not always granted). Maybe someday the Church will see fit to eliminate at least some of the complexities in the current law, which in turn would eliminate a lot of the understandable confusion in the minds of so many Catholics about the different Churches sui iuris.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.