Q1: How come the pro-abortion group “Catholics for Choice” gets away with calling itself a Catholic organization? Why doesn’t the Church stop it from using this name? —Dale

Q2: There’s a school in our diocese that is run by Catholic laywomen. They teach Catholic catechism and the kids regularly go to Mass. But you wouldn’t know from its name that it’s a Catholic school, because it doesn’t say “St. X Catholic School,” but just “St. X School.” It isn’t mentioned in the diocese’s list of Catholic schools, either. Is it safe to assume that this is some schismatic fringe group running a school that claims to be “Catholic” but isn’t in communion with the Pope? I’m worried because one of my Catholic friends is considering sending her children there next year… –Theresa

On the surface, these two questions appear to have little in common, but in fact they both involve the issue of institutions calling themselves “Catholic,” or refraining from doing so. The Code of Canon Law addresses this issue clearly, but the everyday situation in the United States is nevertheless somewhat complicated.

Canon 216, which is included in the section of the code pertaining to the rights and obligations of all the Christian faithful, leaves little room for uncertainty: it states that no initiative can lay claim to the title “Catholic” without the consent of competent ecclesiastical authority. This means, therefore, that even if a group of practicing Catholics wishes to evangelize or promote apostolic action in some way that is totally in keeping with Catholic teaching, they nevertheless cannot start an organization on their own that includes the term “Catholic” in its name. If, say, some Catholic lay people wanted to start a soup-kitchen called “Catholics Against Hunger in the City of X,” and publicly announce that they intended to use every possible means to stamp out hunger in their city completely, they would first need to obtain permission from the competent authority—in this case, the diocesan bishop—to use this name.

There are practical reasons for this. As we have seen before in “Parish Closings,” the diocesan bishop is ultimately responsible for the spiritual wellbeing of the Catholics living in his territory. He is therefore obliged to ensure that the Church’s official teaching is not publicly misrepresented, which naturally could confuse not only the faithful, but non-Catholics as well.

At the same time, there are many sincere, well-meaning Catholic lay persons who may honestly wish to support the interests of the Catholic Church, or promote social justice in the secular arena in the name of Catholicism. While their good intentions may be laudable in themselves and are certainly not prohibited, such people do not have authority to speak for the Church. If an organization indicates that it is “Catholic,” persons who hear about it naturally will assume that it represents the Church’s interests—but if it is run by a group of lay people acting entirely on their own, this is not necessarily so. Such groups can potentially do a lot of harm, by “spinning” the Church’s general teachings about human rights and dignity to support a specific social or political position, which the Church may be neutral about, or which may actually be at odds with Catholicism.

What if, for example, the imaginary “Catholics Against Hunger” group mentioned above were to declare that all local supermarkets have the moral obligation to donate food to the needy? While the Church is hardly opposed to the idea of feeding the poor, there certainly is no theological maxim that requires businesses to give their merchandise away! Yet if people were to hear that this organization was making such pronouncements, they could reasonably conclude, based on its name, that this was the position of the Catholic Church—and of course it is not.

Unfortunately, such groups and the confusion they create do not exist solely in the realm of imagination. In the past few years, an organization called “Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good” has been promoting health-care reform of the sort currently being debated in Congress. Some Catholics may feel that health care is a human right, but the fact remains that the Catholic Church has never officially declared this to be a part of Catholic teaching. The fact that the US Catholic Bishops have publicly been diametrically opposed to some of the very legislation promoted by this organization should be a tipoff that something is wrong here. Yet the news media have, whether through ignorance or malice, directly or indirectly, spread the notion that this group somehow officially represents the Catholic Church, which is completely incorrect.

Other organizations take positions which can never in any way be seen as consistent with Catholic teaching. An obvious example is the organization that Dale mentions. It was originally founded by a former Catholic cleric, who was expelled from both the Jesuit order and the priesthood. His goal was to lobby Washington in support of abortion “rights,” in the name of American Catholics. It goes without saying that while this group publicly calls itself “Catholics for Choice,” it definitely did not obtain permission from church authorities to use the term “Catholic” in its name. To this day, this group claims—falsely, of course—to legitimately represent those Catholics who support abortion, as if the pro-abortion position can ever be a justifiable option for any Catholic! One might argue that since everyone knows the Catholic Church is vehemently pro-life, nobody can possibly think that this group is an officially recognized Catholic organization anyway. But the unfortunate fact is that this group continues to create a good deal of confusion in political circles and in the mass media—because its use of the term “Catholic” wrongly suggests that it represents in some way the Catholic Church.

What can the Church do to correct this sort of abuse? Naturally, bishops can request, and (if this fails) publicly demand that such groups change their names, to avoid confusing and scandalizing the faithful; but since in many cases the beliefs of the founders of these organizations are not in tune with authentic Catholic teaching, it should surprise no one when they fail to comply. After all, the founder of “Catholics for Choice” was expelled from both his religious order and the priesthood, yet the group continued with its name unchanged. If such extreme punishments don’t work, what will? People who are determined to promote an agenda contrary to Catholic teaching are usually not daunted by the knowledge that they are violating canon law and disobeying an injunction from the Catholic hierarchy!

One who might logically think of filing suit in the civil courts for misuse of the name “Catholic” will be disappointed. If “Catholic” were a registered trademark, like “NutraSweet” or “Band-aid,” the Church would be able under US civil law to stop these organizations from using it as part of their title—but this is not the case.

In fact, this is why one sometimes runs across a parish church, school, or other institution calling itself “Catholic” when in fact it is operated by a traditionalist, possibly schismatic group that is not in full communion with the Catholic hierarchy. Such people often claim to be the “true” Catholics, while asserting that the visible Catholic Church under papal authority has fallen into error. We saw in “Are They Really Catholic? Part II” that ordinarily people can easily err sometimes in thinking that they are attending a legitimate Catholic parish—because the misleading sign out front indicates that it is a “Catholic” church.

Speaking of which, let’s turn now to Theresa’s question. Just as no apostolate can call itself Catholic without permission of competent authority, canon 803.3 states that no school can do so either. Once again, the diocesan bishop is ultimately responsible for the education of the people of his diocese in the faith. If a school within his territory purports to be imparting a Catholic education to its students, it is the responsibility and obligation of the bishop to be sure that it is really doing what it says.

In practical terms, this does not mean that the bishop should micromanage every aspect of every school in his diocese. It does mean, however, that he has the right to object to particular religious textbooks and teaching methods if he feels that they poorly or inaccurately convey Catholic teaching. If he wishes, the bishop can also mandate that certain books always be used, so that he knows all schools in his territory are teaching the same material.

In many parts of the US, groups of Catholic parents have started their own schools, for various reasons. Sometimes the diocesan schools are simply too expensive or too far away; sometimes these parents believe that the catechism being taught in the Catholic schools is inferior to what they could teach themselves. Such people are not automatically “schismatic fringe groups”; rather, they are simply operating schools that are not under the direct control of their bishops—and there is nothing inherently illegal about this.

But since the bishop has not formally approved these schools, and does not have direct involvement with or influence on their religious instruction programs, they cannot, under canon 803, call themselves “Catholic” schools. The school that Theresa describes appears to meet this description. Ironically, the very fact that the school she mentions does not call itself “Catholic” in its title is an indication that it is probably run by entirely legitimate Catholics! If it really were being operated by some breakaway group not in communion with the local bishop, its board probably wouldn’t hesitate to use the term “Catholic” in its name.

In this case, the failure of the school Theresa describes to use the term “Catholic” in its name is most likely an indication that it is obedient to church authority. Naturally, any parent considering a new school for his children will investigate further, and it should be relatively simple to get some clarification directly from the school’s principal, and/or indirectly from the diocesan chancery (which certainly should at least be aware of the school’s existence).

We’ve seen, therefore, that there are groups out there calling themselves “Catholic” which really aren’t, while there are others which refrain from using the term “Catholic” as part of their name, but which are operating in complete accord with Catholic teachings. In general, a safe bet for every Catholic who may be confused about a particular organization would be to inquire as to whether it is operating with the approval of church authorities, and if not, to find out why not. As we’ve seen here, there is more to an institution than just the presence or absence of the word “Catholic” in its name.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

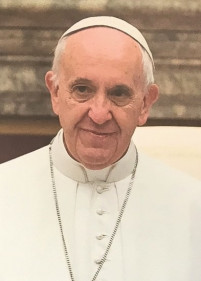

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.