Q: My late uncle was a Dominican priest. When we were kids he used to tell us stories about being a Dominican. I remember one story involving somebody who asked him to hear his confession, but my uncle told him that he couldn’t. He said he only had permission to hear confessions of people who were dying. Does that make any sense to you? Do you think he was being punished for some reason? Don’t all priests have the obligation to hear somebody’s confession if the person asks them to? –Stuart Continue reading

-

If the information on this website has helped you, please consider making a contribution so that it can continue to help others.

-

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Thanks for subscribing!

-

HABEMUS PAPAM!

Pope Leo XIV is an American … AND a canon lawyer. -

canonlawmadeeasy@yahoo.com

Please check the Archives first–it’s likely your question was already addressed.

Unsigned/anonymous questions are not read, much less answered (why is it necessary even to mention this?). About the author

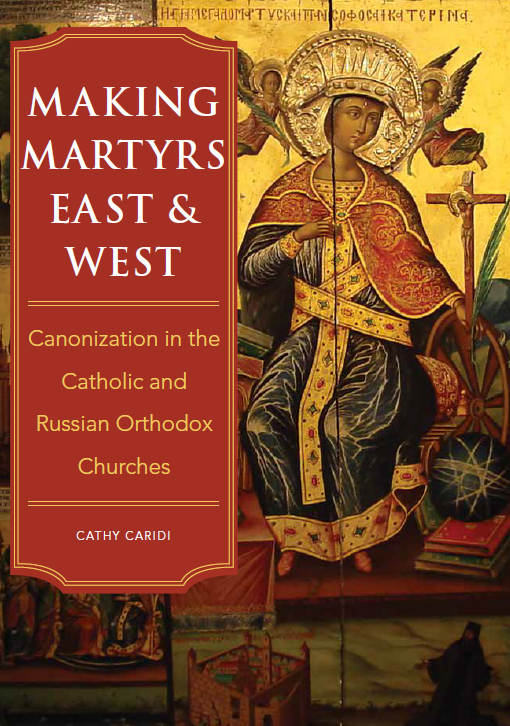

Cathy Caridi, J.C.L., is an American canon lawyer who practices law and teaches in Rome. She founded this website to provide clear answers to canonical questions asked by ordinary Catholics, without employing all the mysterious legalese that canon lawyers know and love. In the past Cathy has published articles both in scholarly journals and on various popular Catholic websites, including Real Presence Communications and Catholic Exchange.