Q: I read your “Obedience and Canon 1752,” about the people in Texas who claim God is telling them the Pope is a usurper. It led me to wonder: did the bishop of that diocese ever investigate their alleged claims to divine apparitions? Did he establish whether God really is speaking to them or they’re lying frauds? It doesn’t sound like the bishop ever stopped to consider that maybe they’re having genuine mystical experiences. Do you know if there was any diocesan investigation?

… I’m not saying that these people are legit. Their disobedience instantly tells me their messages are not from God. However, it would be more helpful for the bishop to tell the public that these alleged claims to apparitions from God are based on mental illness or daydreams or fakery, based on an impartial investigation into the facts. In my opinion this would be a more factual message to the diocese than “I didn’t like what they’re saying, so I told them to be quiet, and they refused.” It would be easier for ordinary Catholics to accept too, I think… —Rosie

A: Rosie raises an excellent point about the situation in the Archdiocese of San Antonio, discussed here in the previous article she mentions. If, let’s say, a member of the faithful claims to be having visions of the Blessed Virgin, or hearing locutions (i.e., verbal messages) from Jesus, or a statue or crucifix appears to be weeping/bleeding, what’s the local bishop supposed to do?

This question is quite timely, because the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) just recently amended the process for determining the authenticity (or not) of alleged apparitions and other supernatural events. Entitled “Norms for Proceeding in the Discernment of Alleged Supernatural Phenomena,” the new procedure was approved by Pope Francis and formally took effect on Pentecost Sunday of this year. The new procedure replaces an investigative process that was established by Pope Paul VI in 1978. Let’s first look at how the old process used to work, and then at what’s been changed by the 2024 Norms. Finally, we’ll see what we can conclude about the situation in San Antonio.

Previously, when a Catholic alleged that “the Virgin Mary appeared to me and said X,” or made some comparably supernatural claim, the 1978 Norms declared that it was the responsibility of “Ecclesiastical Authority” to examine the facts and make a determination (see the Preliminary Note). In case you’re wondering, it’s made perfectly clear later in the document that by “Ecclesiastical Authority,” Rome meant the Ordinary—which canon law defines as the diocesan bishop, any episcopal vicar(s), and the vicar general. In the case of alleged supernatural events within a clerical religious institute/involving any of its members, the term “Ordinary” refers also to the major superior (c. 134.1).

In other words, Rome didn’t get involved in these cases right off the bat. In fact, Rome didn’t have to get involved at all, unless the bishop asked it to intervene (Section IV, 1a). That said, if the alleged visions (or other events) had already become well known in multiple dioceses, the Vatican could choose to intervene on its own initiative: as the 1978 Norms phrased it, Rome would become involved “in graver cases, especially if the matter affects the larger part of the Church, always after having consulted the Ordinary and even, if the situation requires, the Conference of Bishops” (Section IV 1.b).

Section I of the 1978 Norms described the criteria for determining whether alleged supernatural events were in fact authentic. These included the personal qualities of any purported seer(s), such as their manner of life and their mental stability; the theological soundness of any message(s) allegedly received from Heaven; and any evidence of personal profit, financial or otherwise, by those involved in the alleged event.

The 1978 Norms seem clear enough; so why did they need updating? The introductory “Presentation” of the 2024 Norms includes a section called “Reasons for the New Norms,” and it answers this question in extensive, helpful detail. (This explanation, incidentally, stands in marked contrast to the vague justification provided for the 2020 changes in the procedure for establishing new diocesan religious institutes—see canon 579 and “Founding New Religious Institutes: Pope Francis Changes the Law (Episcopal Authority, Part II)” for more on this.)

Among other things, the “Reasons” section notes that the 1978 Norms left the investigation of purported supernatural events to individual diocesan bishops, but different bishops were subsequently found to be handling these cases in different ways—with some bishops apparently failing to handle them at all. Such a lack of consistency was obviously problematic, and prompted Rome to require now that bishops “dialogue” with the Vatican on these matters (more on this in a moment).

Now, if somebody claims that “the Virgin Mary appeared to me and said X,” only the local bishop himself (and not the other people falling under the definition of “the Ordinary,” as was possible before) is responsible for examining the alleged event(s). He is to do this, however, “in dialogue with the national Episcopal Conference” (Section II A.1; in “Are Catholics Supposed to Abstain From Meat Every Friday?” we took a look at what a Bishops’ Conference, a.k.a. an Episcopal Conference, is and does.)

If the phenomena do not have “the semblance of truth” (Section II B.7.1)—if, e.g., it immediately becomes clear that the claimant was kidding, or admits to being mistaken, or is manifestly suffering from mental illness (etc.)—the bishop can end the investigation right there. Nevertheless, he is still required to consult with the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) in Rome about the alleged event(s), and the DDF will presumably maintain some record of the incident (Section II B.7.2).

But if the bishop’s initial inquiries suggest that there might really be something supernatural going on, he is required to establish an Investigatory Commission (Section II B.8.1), including a theologian, a canonist, and (as appropriate) a medical doctor or other expert(s). To take an obvious example, if a person is claiming to have received the stigmata, it’s only logical that the Commission include medical experts who can assess its (in)authenticity. Or if someone is asserting that objects have “miraculously” turned to gold, it makes sense to have some professional on the Commission who is able to test these objects, and confirm or disprove the claim. In other words, the diocesan bishop, who is almost certainly not an expert in these sorts of matters, is not to make a judgment without first obtaining the professional opinion of others who are.

Once the bishop reaches a conclusion as to the veracity of the alleged phenomena, he is to draw up a report and send it to the DDF. Note that the bishop is not to make his conclusions public unless and until the DDF confirms his opinion and gives its approval (Section II B.19-21).

The phraseology of any official, publicly pronounced determination on such phenomena has been changed too. Previously, in accord with the 1978 Norms, bishops generally either declared that an event was indeed “supernatural,” thus indicating that it was from God; or “not supernatural,” meaning that it wasn’t. But as the 2024 Norms explain (see “Reasons for the New Norms”), this terminology understandably confused many Catholics: if the bishop declares authoritatively that “yes, this apparition/weeping statue/etc. is the work of God Himself,” does that mean all Catholics are obliged to believe in it? Many Catholics naturally thought so! In reality, though, Catholics aren’t required to believe in anything which has happened in church history after the deposit of faith was closed over 1900 years ago. (A clear, concise overview of exactly what the deposit of faith is can be read here.) For this very reason, the Church has certainly declared many Marian apparitions to be “worthy of belief,” but because such relatively recent events are not part of the Church’s deposit of faith, Catholics are free to accept them or not, as they see fit.

There were other types of confusion, inadvertently caused sometimes by a bishop’s choice of words. The events which took place in Garabandal, Spain constitute a good example of  this. After extensive investigations of purported apparitions of the Blessed Virgin to four local girls in the 1960’s, more than one bishop of that diocese concluded over the years that their supernatural character could not be confirmed (in Latin, non constat de supernaturalitate); and when the Vatican was asked by one bishop to weigh in, it reached the same conclusion. Many Catholics wrongly understood this to mean that the alleged events had been condemned by the Church as false, but that’s not what the phrase meant at all! The bishops were simply saying that they were unable to reach a definitive conclusion, one way or the other; they were not saying that they’d concluded the events were caused by trickery or error or diabolical influence. By this point, it should be evident that the terminology being used in these sorts of situations required revision, for clarity’s sake.

this. After extensive investigations of purported apparitions of the Blessed Virgin to four local girls in the 1960’s, more than one bishop of that diocese concluded over the years that their supernatural character could not be confirmed (in Latin, non constat de supernaturalitate); and when the Vatican was asked by one bishop to weigh in, it reached the same conclusion. Many Catholics wrongly understood this to mean that the alleged events had been condemned by the Church as false, but that’s not what the phrase meant at all! The bishops were simply saying that they were unable to reach a definitive conclusion, one way or the other; they were not saying that they’d concluded the events were caused by trickery or error or diabolical influence. By this point, it should be evident that the terminology being used in these sorts of situations required revision, for clarity’s sake.

Consequently, the 2024 Norms have changed the wording that may be used, creating six different categories that explain much more clearly what the Church’s finding is (Section I B.16-23). Among others, they include Sub mandato, which means that an event has been found to be of supernatural origin, but individuals in the Church are abusing it, perhaps gaining notoriety or money from their connection with it (Section I B.20); and Curatur, meaning that an investigation has raised serious questions about the event, but the faithful have already embraced it and are deriving spiritual benefit from it—so the bishop is asked not to condemn it outright, but not to encourage it either (Section I B.19). You can see how much more nuanced the new categorization is, compared to the previous system.

So how does the situation in San Antonio, Texas fit into all this? Before saying anything, it’s critical to bear in mind that we don’t know the details of the interactions between the Archbishop of San Antonio, and the members of the Mission of Divine Mercy (who claim that some of their members have been receiving messages from Heaven). And this is not surprising, because it would hardly be appropriate for the Archdiocese to make public every detail of what transpired in his meetings with the members, and what was said in the course of their conversations. We only know what we have been told by the Archbishop in his public statements and decrees, and what the Mission has posted on its website.

That said, however, when you look closely at the wording of what has been made public, the Archbishop himself appears to be admitting that there has been no investigation of the alleged supernatural phenomena at the Mission of Divine Mercy. For example, the Archbishop said in his March 15, 2024 “public statement” (found here, the final document at the bottom) that

The only stipulation I have ever requested of the MDM–in order to prevent any misunderstandings and possible scandal–was to refrain from publishing any alleged prophetic message until they were reviewed to ensure they were not harmful to the people of God.

This would certainly indicate that at the time of the stipulation, no “review” of the alleged messages from Heaven had been done. The Archbishop doesn’t mention when he made this stipulation, so it’s hard to reconstruct a time-frame here. Were the messages reviewed at a later date? Possibly—but if so, the Archbishop doesn’t mention it.

Subsequently, the Archbishop wrote another letter to the priest-Guardian of the Mission of Divine Mercy, which he made public on the archdiocesan website here. Dated April 24, 2024, the letter urges the priest-Guardian to “cease publishing the alleged prophecies, until they can be evaluated by proper Church authority.” This phrasing indicates even more clearly that no such evaluation (or “review,” as mentioned previously) has been done, by the Archbishop or anyone else.

Consequently, Rosie seems to be on fairly solid footing when she says in her question that it sounds like the Archbishop simply said in effect, “I didn’t like what they’re saying, so I told them to be quiet.” How could/should this whole sad mess have been handled in accord with the Vatican’s norms?

Since these events all transpired before the 2024 Norms took effect, they were governed by the older Norms of 1978. As already mentioned above, under the 1978 Norms the Ordinary was responsible for investigating the situation:

When Ecclesiastical Authority is informed of a presumed apparition or revelation, it will be its responsibility: (a) first, to judge the fact according to positive and negative criteria… (Preliminary Note)

The 1978 Norms then proceed to describe both the “positive and negative criteria” in the very next section, entitled “Criteria for judging, at least with probability, the character of the presumed apparitions or revelations.”

It’s unclear when the Archbishop first heard of these alleged messages; in fact, for all we know it might have been his predecessor who initially found out about them. According to the 1978 Norms (and the 2024 Norms too, for that matter), ignoring the situation was not an option: both sets of Norms state that the Ordinary/Bishop is “responsible” for conducting an investigation. If even the simplest inquiries quickly revealed that the Mission’s claims were manifestly baseless from the start, then there should be a record of this finding somewhere, and the Archbishop should be able to cite it now.

Similarly, if the Archdiocese had been in the midst of conducting an investigation when the Mission decided to publicize the alleged messages, the Archdiocese could simply say so. It would only have been logical to order the Mission to keep the alleged revelations private, at least until the investigation had concluded—but judging by what the Archbishop has said publicly, that’s not what happened.

By now some readers might be tempted to object, “Why would an investigation be necessary? Listen to what these so-called messages from Heaven are saying about the Pope and the bishops! How could this possibly be coming from God?” Actually, this in itself is one very good reason why there needs to be an investigation into such cases! Here’s why.

Imagine that a person is genuinely receiving revelations from God … but because this person is cloistered, or bed-ridden/hospitalized/handicapped (etc.), somebody else is sharing these revelations with the world. Now imagine that the other person is changing the wording, supposedly in order to “fix” the terminology so it flows better; or is simplifying the phrasing so that it’s easier to understand. In this sort of scenario, the actual recipient of authentic supernatural messages might very well be giving accurate accounts of what he saw and heard—but these accounts are being garbled by someone else before they reach the public.

We don’t have to imagine this situation, because it has really happened, and the resulting confusion has delayed the canonization of a genuinely holy mystic for nearly two centuries.

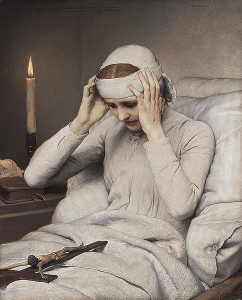

Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774-1824) was a German Augustinian, confined to her bed due to ill health. She began to have regular visions of the life of Our Lord, of many Old Testament events, and of early Christian saints—and her visions soon began to attract

“The Ecstatic Virgin Anna Katharina Emmerich” by Gabriel von Max, 1885. Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

attention. A poet named Clemens Brentano met Sister Emmerich and soon became her secretary, for many years faithfully sitting by her bed and transcribing her visions as she recounted them. After her death, Brentano published Emmerich’s account of the Passion of Christ (which included events used by Mel Gibson in his film of that name, by the way!), and eventually multiple volumes of Emmerich’s visions were put into print. They are still widely read today.

Many devout readers of Sister Emmerich’s works wrongly regard them as scrupulously accurate. In fact, they are anything but—because Brentano routinely “corrected” her statements, added additional information without identifying his own interpolations as such, and generally tidying up (in his mind, at least) a lot of perceived loose ends in Emmerich’s accounts of what God showed her.

In the years after the death of Anne Catherine Emmerich, her cause for canonization was opened—and was stalled precisely because of questionable statements contained in these books of her revelations. (We don’t know the precise details, since the minutes of meetings of those involved in the canonization process are normally not released to the public.) For many decades, Sister Emmerich’s road to sainthood was closed, because the Church maintained that an authentic mystic and saint would not have received some of the messages which Emmerich supposedly recounted. It was only in the 1970’s that her cause was reopened—and it made pretty rapid progress, once the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints determined that the writings long attributed to Emmerich were to be disregarded, as largely the work of another. Emmerich was beatified in 2004.

The Church investigated Sister Emmerich extensively, both during and after her life, and her mystical experiences were determined to be authentic. But because Clemens Brentano got ahold of her revelations and rewrote them to an unclear extent, and then presented his work as the words of Sister Emmerich, her heroic sanctity came into question for generations. To this day, Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich’s purported revelations are easily obtained, in many languages; but nobody is sure how much of their content is from God, and how much is actually the fanciful work of her secretary. (A good overview of this story can be found here.) It should be clear from this case why an investigation of an alleged mystic’s experiences is necessary, even if his so-called revelations from God are questionable.

Returning to the case in San Antonio, there might conceivably be some back-story here happening behind the scenes, something which we know nothing about. To cite another example, in decades past a priest from a major archdiocese left the Catholic Church, and with great fanfare he established his own. When news media tried to get information from the archdiocese, chancery officials were reticent—leading many to conclude at the time that the archdiocese really didn’t care! In reality, however, the priest had a long history of mental problems and psychiatric treatment, and the archdiocese was doing everything in its power to protect the priest’s reputation in the public eye, while it strove behind the scenes to get him back into the Church and into the psychiatrist’s office. The vague remarks made to journalists by officials of the archdiocese may have sounded noncommittal, but they were really intended to protect this priest’s privacy and his reputation. Consequently, it seemed at the time that the archdiocese wasn’t doing much to rectify the situation, whereas the true story was completely different.

For the record, this is not to suggest that the members of the Mission of Divine Mercy have mental problems! The point is simply that things could be happening in Texas quietly, out of the public eye, and the Archbishop and his staff may in fact be doing a lot which they can’t reveal openly (at least not yet).

All that said, if the Archbishop has indeed done nothing to launch an investigation into the alleged supernatural phenomena at the Mission of Divine Mercy, any investigatory process would now have to be initiated under the new, 2024 Norms—meaning that whatever conclusion the Archbishop might draw from his own investigation must be sent to the DDF and approved by them. The added layer of review by Rome, of course, will make investigation of any phenomena take longer.

If we return now to Rosie’s question, we can see how on-target she was. At the same time, we’ve also seen that there could potentially be a lot happening in this case which is rightly being kept out of the public eye. When a Catholic claims to be experiencing some sort of supernatural phenomena, Rome requires that the local bishop investigate it. If it’s real, we should all want to acknowledge God’s actions as such; and if it’s not, the faithful need to be informed that it’s something to avoid.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.