Q: When reading news about Fiducia Supplicans, and then reading the declaration itself, I was struck by this statement it contains about the Church’s Magisterium:

Such theological reflection, based on the pastoral vision of Pope Francis, implies a real development from what has been said about blessings in the Magisterium and the official texts of the Church.

I always thought that the “Magisterium” was the body of Catholic faith as it has always been taught by the Church, and it can’t be changed. Can it really be “developed,” as the text claims?

At first, I assumed that this was a theological question and not a matter for canon law. Then I began to realize that at least it seems like Pope Francis and Cardinal Fernández [the Prefect of the Dicastery of the Doctrine of the Faith] may actually be violating the Magisterium by making a declaration contrary to it. This sounds a lot like heresy…. That subsequently led me to read your post, “Can a Pope Commit Heresy?” which shows that canon law is possibly involved here.

… [T]he more I read and research and objectively try to understand what Fiducia Supplicans means, and what the Pope is doing by making this declaration, and what this implies for the Catholic Church, the more confused I get. Is there a simpler way to make sense of this? Can canon law help? —Paul

A: Paul is, of course, referring to Pope Francis’s recent Declaration “On the Pastoral Meaning of Blessings,” regarding the blessing of same-sex couples. This document has naturally garnered a lot of attention not only from the Catholic faithful, but also from the secular press, who breathlessly (and falsely) announced that it has “reversed” the Church’s teaching on homosexuality. So much has already been written about Fiducia Supplicans [FS], by so many who either haven’t bothered to read it or don’t seem to care what it actually says, that there’s little wonder Paul and so many other Catholics are confused!

Paul’s approach to sorting out what’s going on here is entirely logical and thus commendable—and the questions he asks are very valid ones. While nobody should expect canon law to be able to completely untie this Gordian knot of a problem that’s now been inflicted upon the Church, we can at least take a look at the specific aspect which Paul raises: the meaning of the term Magisterium, the possibility of changes to it, and the role of canon law in understanding this new document. First, however, it’s necessary to take a look at what FS actually says, in the context of an earlier document on the same subject, issued by the same office of the Vatican less than three years ago.

Back in March 2021, then then-Congregation (and now Dicastery) of the Doctrine of the Faith issued a negative response to a dubium which had been proposed: “Does the Church have the power to give the blessing to unions of persons of the same sex?” Cardinal Ladaria, then the Prefect of the CDF. explained why this is impossible, quoting in the process from the Roman Ritual, one of the Church’s official liturgical books:

Blessings belong to the category of the sacramentals, whereby the Church “calls us to praise God, encourages us to implore His protection, and exhorts us to seek His mercy by our holiness of life.” In addition, they “have been established as a kind of imitation of the sacraments, blessings are signs above all of spiritual effects that are achieved through the Church’s intercession.”

Consequently, in order to conform with the nature of sacramentals, when a blessing is invoked on particular human relationships, in addition to the right intention of those who participate, it is necessary that what is blessed be objectively and positively ordered to receive and express grace, according to the designs of God inscribed in creation, and fully revealed by Christ the Lord….

For this reason, it is not licit to impart a blessing on relationships, or partnerships, even stable, that involve sexual activity outside of marriage (i.e., outside the indissoluble union of a man and a woman open in itself to the transmission of life), as is the case of the unions between persons of the same sex. The presence in such relationships of positive elements, which are in themselves to be valued and appreciated, cannot justify these relationships and render them legitimate objects of an ecclesial blessing, since the positive elements exist within the context of a union not ordered to the Creator’s plan.

Furthermore, since blessings on persons are in relationship with the sacraments, the blessing of homosexual unions cannot be considered licit. (Emphases added)

In the accompanying Article of Commentary, Cardinal Ladaria made at the time a critical distinction that is directly relevant to our discussion:

The Note is centered on the fundamental and decisive distinction between persons and the union. This is so that the negative judgment on the blessing of unions of persons of the same sex does not imply a judgment on persons.

The answer to the proposed dubium does not preclude the blessings given to individual persons with homosexual inclinations, who manifest the will to live in fidelity to the revealed plans of God as proposed by Church teaching. Rather, it declares illicit any form of blessing that tends to acknowledge their unions as such. (Emphases added)

Let’s fast-forward now to December 2023. Declaring that “Blessings are among the most widespread and evolving sacramentals” (paragraph 8), FS makes a different distinction, between blessings “from a strictly liturgical point of view” (9), and “a more pastoral approach to blessings” (21). After differentiating between these two described categories of blessings, Cardinal Fernández concludes that

Therefore, the pastoral sensibility of ordained ministers should also be formed to perform blessings spontaneously that are not found in the Book of Blessings.… [I]t is essential to grasp the Holy Father’s concern that these non-ritualized blessings never cease being simple gestures that provide an effective means of increasing trust in God on the part of the people who ask for them, careful that they should not become a liturgical or semi-liturgical act, similar to a sacrament. (35-36)

Applying this to homosexual couples, he notes that

Within the horizon outlined here appears the possibility of blessings for couples in irregular situations and for couples of the same sex, the form of which should not be fixed ritually by ecclesial authorities to avoid producing confusion with the blessing proper to the Sacrament of Marriage. In such cases, a blessing may be imparted that not only has an ascending value but also involves the invocation of a blessing that descends from God upon those who—recognizing themselves to be destitute and in need of his help—do not claim a legitimation of their own status, but who beg that all that is true, good, and humanly valid in their lives and their relationships be enriched, healed, and elevated by the presence of the Holy Spirit…. Indeed, the grace of God works in the lives of those who do not claim to be righteous but who acknowledge themselves humbly as sinners, like everyone else. (31-32, emphasis added)

Note that the terminology here involves blessing homosexual persons, not their sexual union itself. (And while we’re here, note also how complicated it is for an ordinary Catholic, who does not have an advanced degree in theology, to read through FS and sort out what it’s actually saying.)

Perhaps the clearest, most understandable assertions of all are found in paragraph 39 of FS:

In any case, precisely to avoid any form of confusion or scandal, when the prayer of blessing is requested by a couple in an irregular situation, even though it is expressed outside the rites prescribed by the liturgical books, this blessing should never be imparted in concurrence with the ceremonies of a civil union, and not even in connection with them. Nor can it be performed with any clothing, gestures, or words that are proper to a wedding. The same applies when the blessing is requested by a same-sex couple. (Emphases added)

Since this paragraph of FS makes it so abundantly clear that the document is not authorizing the wedding-like blessing of homosexual couples, you really have to wonder why the secular fake-news media are so anxious to tell the world that this is precisely what it does. In fact, the very next day employees of the New York Times were conveniently present to report on the blessing of a “married” homosexual couple by none other than Jesuit Fr. James Martin, who later declared to the Times, “It was really nice to be able to do that publicly.” If this was not a publicity-stunt, intended deliberately to confuse the Catholic faithful even further about what the Church teaches about homosexuality, and about what FS really says … then it’s hard to understand why it took place at all. Although FS 31 specifically states (as noted above) that a blessing may be given to those in irregular marriage situations who “do not claim a legitimation of their own status,” it’s obvious that this is exactly what the “married” couple in this case (as well as Fr. Martin himself) were doing.

So what does all this have to do with the Church’s Magisterium? Before answering, we must first define the term. Magisterium refers to the teaching authority of the Church, as handed down by the Pope and the bishops in communion with him. The Catechism explains it this way:

“The task of giving an authentic interpretation of the Word of God, whether in its written form or in the form of Tradition, has been entrusted to the living teaching office of the Church alone. Its authority in this matter is exercised in the name of Jesus Christ.” This means that the task of interpretation has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome.

“Yet this Magisterium is not superior to the Word of God, but is its servant. It teaches only what has been handed on to it. At the divine command and with the help of the Holy Spirit, it listens to this devotedly, guards it with dedication and expounds it faithfully. All that it proposes for belief as being divinely revealed is drawn from this single deposit of faith.”

The Church’s Magisterium exercises the authority it holds from Christ to the fullest extent when it defines dogmas, that is, when it proposes truths contained in divine Revelation or also when it proposes in a definitive way truths having a necessary connection with them. (CCC 85, 86, 88, emphases added)

Because this is an abstract theological concept, in actual practice it can at times become extraordinarily tricky to determine whether a particular statement by church officials constitutes “the Church’s Magisterium” or not. Among other things, it’s important to remember that the Magisterium involves teachings—which means that purely procedural sorts of statements (e.g., an announcement that Father X will be the new bishop of Diocese Y) aren’t magisterial at all. As we saw in “How Often Does the Pope Change Canon Law?” Pope John Paul II issued his motu proprio Ad Tuendam Fidem in 1998, changing canons 750 and 1371 (which was later renumbered as canon 1365) of the Code of Canon Law, specifically to clarify which sorts of teachings are magisterial and which aren’t.

This wasn’t some empty semantic exercise on Pope John Paul II’s part, either: as Paul rightly notes, Catholics are required to accept the teachings of the Magisterium—and in some cases, failing to do so constitutes heresy, which is an excommunicable offense (c. 1364.1). That’s why for us Catholics, understanding what the Magisterium is all about can be serious business! This was discussed at great length in “Can a Pope Commit Heresy? (‘Heresy’ Defined),” which explained in great detail the manner in which we Catholics are obliged to accept various types of church teachings, as outlined in canons 750 ff.

Armed with this basic understanding of the term “Magisterium,” let’s now return to Paul’s question. Can the Magisterium change—or does it always remain the same? Well, a brief look at church history will show that new magisterial pronouncements have indeed been made at various points in the past two millennia: to cite a couple of enormously significant examples, in the year 325, the bishops at the Council of Nicaea declared authoritatively for the first time that Jesus Christ was both God and man; and at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 they further explained that Christ was/is one Person with two different natures, one human and one divine. And yes, a failure to embrace either of these teachings of the Magisterium can at least potentially lead to excommunication, as per canons 750 and 1365.

On the one hand, you can certainly say that “the Magisterium changed” with each of these official pronouncements, since the Church had not explicitly taught these things before; but on the other hand, these magisterial declarations didn’t contradict anything that the Church had authoritatively taught in the past. The Church had never taught, e.g., that Christ was merely human and not divine—instead, the Church had never before taught anything authoritatively on the subject, one way or the other!

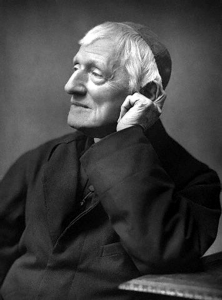

What we see in these two examples is something which has happened repeatedly over the course of time: the Church’s doctrine has never, ever been reversed, but it has in many  instances been developed in a fuller, more detailed way. Understanding the concept of the development of doctrine was what helped Saint John Henry Newman, who was raised in the Anglican communion, to ultimately embrace the Catholic faith—and his own book-length explanation of this very concept remains a Catholic theological classic. (If you’re understandably not able to stop and read Newman’s entire book, here’s a far shorter, succinct summary by Capuchin Fr. Thomas Weinandy, a rock-solid Catholic theologian of our own day.)

instances been developed in a fuller, more detailed way. Understanding the concept of the development of doctrine was what helped Saint John Henry Newman, who was raised in the Anglican communion, to ultimately embrace the Catholic faith—and his own book-length explanation of this very concept remains a Catholic theological classic. (If you’re understandably not able to stop and read Newman’s entire book, here’s a far shorter, succinct summary by Capuchin Fr. Thomas Weinandy, a rock-solid Catholic theologian of our own day.)

So now Paul has the answer to his first, more general question: yes, the Church’s Magisterium can change, in the sense that it can develop—but it can never contradict its own previous magisterial teachings. Now the next question is, does the content of FS constitute magisterial teaching?

As Paul correctly indicates, Cardinal Fernández suggests that it does. But note that he doesn’t actually say that blessing homosexual couples is Catholic teaching; if he did, he would be directly contradicting the Church’s teaching on homosexuality, which is ultimately grounded in Sacred Scripture (see “Who is Qualified to Become an Extraordinary Minister of Holy Communion?” and “Could Canon Law be Changed to Permit Gay Marriage?” for more on what the Church teaches on this subject and why). Rather, what Cardinal Fernández asserts is “a development” is the notion of blessings in the Church, which (as was discussed above) he declares can be divided into two different categories, “liturgical” blessings and “pastoral” ones.

If you read FS in its entirety, you’ll notice that Cardinal Fernández cites no Scripture, or papal pronouncements, or conciliar teachings that make this two-fold distinction—because there aren’t any. This is a new assertion without a history, being made by a single cleric in the Church. Yes, he claims that Pope Francis holds this same position, and maybe that is true (although he hasn’t been teaching this publicly, in any explicit way); but even so, a statement uttered by one Pope, with no tradition—and no theology!—behind it, and which has never been embraced by other bishops around the world, or even mentioned in an ecumenical council (etc.), does not constitute a magisterial teaching which we Catholics are ipso facto required to accept.

You don’t have to take the word of a canon lawyer on this issue. Cardinal Gerhard Müller is the former Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith—a predecessor to Cardinal Fernández in that role—and he promptly criticized FS along these same basic lines, referring to “new practices which have just been invented,” and dubbing the document “self-contradictory.” His detailed analysis of everything theologically wrong with FS, and of the claim that it constitutes magisterial teaching, is well worth a read.

But this isn’t the first time that Cardinal Fernández has pulled a new church teaching out of the air. A few months ago, in an interview with a Catholic journalist, Fernández declared that

When we speak of obedience to the magisterium, this is understood in at least two senses, which are inseparable and equally important. One is the more static sense, of a “deposit of faith,” which we must guard and preserve unscathed. But on the other hand, there is a particular charism for this safeguarding, a unique charism, which the Lord has given only to Peter and his successors…. Today only Pope Francis has it.

Cardinal Fernández then went on to critique those who challenge the Holy Father’s statements, saying, “that would be heresy and schism. Remember that heretics always think they know the true doctrine of the Church.” Really? According to Fernández, nobody can question anything that Pope Francis says (or the content of any document that he signs), because of this “charism” he mentions—a charism which has never before been mentioned in Catholic teaching! This astonishing statement directly conflicts with actual Catholic teaching on the vast-yet-limited authority of the Pope, discussed at length in “When Does the Pope Speak Infallibly?” and “Are There Any Limitations on the Power of the Pope?” Once again, we see Cardinal Fernández dividing a longstanding Catholic theological concept into two new, separate categories—categories which are historically unprecedented and theologically unjustifiable.

As surely everyone knows by now, the ambiguity and the contradictory language of FS is already causing confusion and disunity throughout the Universal Church, with some bishops saying one thing, while others say the opposite. This prompts yet another question: why is this happening? While nobody of course knows for sure, two possibilities have arisen.

The first, unsurprisingly, involves an agenda, and it may have been revealed in the abovementioned interview given by Cardinal Fernández just last year. At one point in their discussion, Fernández made this statement, which seems completely innocuous only if you fail to catch the first three words:

At this point, it is clear that the Church only understands marriage as an indissoluble union between a man and a woman who, in their differences, are naturally open to beget life.

Ironically, this “understanding of marriage” is an example of the Church’s magisterial teaching, the Catholic understanding of marriage as God intended it, which has been with us practically since Adam and Eve. Certainly, many elements of this doctrine have developed over time: to cite just one example, the Church’s position that “consent makes a marriage” evolved over the centuries (see “Marriage and Annulment” and “Sacraments and Personal Identity,” among others, for a discussion of matrimonial consent and its effect on marriage validity). But while the Church’s teaching on the sacrament of marriage have been fleshed out more fully over the course of centuries, the fundamental notion of what a marriage is has not changed—because it cannot be changed. Thus the very idea that the Church’s position that “marriage [is] an indissoluble union between a man and a woman” is only clear “at this point” in time should sound alarm-bells that something gravely heterodox may be in the works.

Who knows, perhaps this is why Fr. James Martin, who as we saw blessed the gay couple in the presence of the New York Times, tweeted out, “Be wary of the “Nothing has changed” response to today’s news. It’s a significant change.” (Incidentally, if FS really represents the Church’s Magisterium, how can it constitute “a significant change”? You can’t have it both ways!) The gay lobby in the Church—which unquestionably exists, as was discussed in “Why Would a Catholic Cleric Desecrate an Altar?”—may be intending to use the ambiguities of FS as a sort of first step toward attempting to legitimize homosexuality in the Church.

There is a second possible reason why FS was promulgated, and it was obliquely touched on by the archbishop of Montevideo, Uruguay, when he said reasonably, “I don’t think it was a topic to be brought out now at Christmas.” He’s right, of course, that the issuance of such a controversial document just one week before Christmas doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense! Unless you realize that on Saturday, December 16, Vatican City judges issued a verdict in the trial of Cardinal Angelo Becciu on corruption charges—and for the first time in history, a cardinal was convicted by lay judges and sentenced to 5 ½ years imprisonment. The charges stemmed from the circumstances surrounding the purchase of London real estate using funds donated to the Church for charitable purposes, discussed in “Using (and Misusing) Donations to the Church.”

Needless to say, the image of a cardinal from the Vatican (and a canon lawyer, who had once also been a close advisor to Pope Francis) being sent off to prison for corruption would normally be the stuff of journalists’ dreams, providing them fodder for countless headlines and stories for months to come. But since FS was suddenly released about 48 hours later, reporters’ attention quickly shifted from “clerical corruption” and “money laundering,” to “blessing homosexual couples.” It certainly was a convenient distraction, and we can only wonder how coincidental the timing of the promulgation of FS really was.

If we return now to the last of Paul’s original questions (“Can canon law help?”), it should be evident by this point that the Code of Canon Law can, in conjunction with theology, provide some clarity on the matter of the Magisterium … but it can’t eliminate all the contradictions, ambiguities, and general confusion surrounding FS, any more than Catholic theology can. Maybe it’s best to end with a comment by Catholic theologian Fr. Thomas Weinandy, who was referenced earlier in a different context, and who did his best to analyze FS from a theological perspective:

In [FS], there is the appearance of reason, but also a great deal of jargon, sophistry, and deceit…. [It] may be well intended, [but] it wreaks havoc on the very nature of blessings. Blessings are the Spirit-filled graces that the Father bestows upon his adopted children who abide in His Son, Jesus Christ, as well as upon those whom He desires to be so. Attempting immorally to exploit God’s blessings makes a mockery of His divine goodness and love.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.