Q: I know you wrote a book about canonizing saints … [and so] it would be helpful if you’d please weigh in on the issue of sainthood and incorrupt bodies.

I assume you’ve heard about the discovery of the incorrupt body of Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster in Missouri (USA). A bunch of women from our parish jumped on a bus and ran to see her body. Now they are pontificating on her sainthood and already preparing verbal attacks on the Vatican and the Pope himself, if they don’t declare her a saint based on this miracle.

What’s the connection between somebody’s body being found to be incorrupt, and their canonization as a saint? …[W]e have lots of saints whose bodies are not incorrupt, otherwise we wouldn’t have so many bone-relics of saints out there… –Craig

A: As we saw in “How Many Miracles are Required to Canonize a Saint?” canonization procedures do constitute a part of canon law, but today they are not found in the actual code itself (c. 1403.1). This canon notes simply that canonizations are governed by special pontifical law, promulgated separately from the Code. In 1983 Pope John Paul II reworked the canonization process, which is outlined in his Apostolic Constitution Divinus Perfectionis Magister—the “special pontifical law” referenced by canon 1403.1. This document is entirely silent on the issue of incorrupt physical remains, and that fact in itself should answer many of the questions that have recently been raised by the exhumation of the deceased sister whom Craig mentions.

But for the sake of clarity, let’s see what (if any) connection has existed historically between the canonization of a saint in the Catholic Church, and the finding that the saint’s body had inexplicably failed to decompose in accord with the laws of nature. Let’s also examine what “incorrupt” means—and doesn’t mean. Then we can examine the specific case of Sister Wilhelmina, and apply the Church’s current canonization process to this interesting situation. Finally, we can draw some conclusions about the “bunch of women from our parish,” who Craig says are “already preparing verbal attacks” on the Church if they don’t get their way.

To begin with, in the nearly 2000-year history of the Church there has never been a requirement that the body of a prospective saint be incorrupt. Craig is absolutely right that the only reason why we “have so many bone-relics of saints out there” is that virtually all of the bodies of our canonized saints have decomposed, just like the bodies of everyone else. The early Church had no hesitation in venerating the very first Christian martyrs, starting of course with the protomartyr St. Stephen (Acts 7:57-60), although their remains were never claimed to be incorrupt. On the contrary, early Christian texts are loaded with references to the “bones” of the martyrs, which obviously indicates that their bodies had decayed.

That said, for those of us who believe in an omnipotent God, there’s no reason why He couldn’t choose to preserve the body of a particularly holy man or woman if He wished, as a sign to the world of that person’s sanctity. Hagiography is filled with stories of saints whose bodies were found to be “miraculously” incorrupt, many of whom remain that way today and are still venerated as such by Catholic pilgrims. Not one of them, however, was canonized a saint solely because his/her body was found intact many years after death. And we should all breathe a sigh of relief that this is so—because in far too many cases, modern science can show that there was nothing necessarily “miraculous” about the failure of the saint’s body to decompose, even if the faithful wrongly reached that conclusion centuries ago.

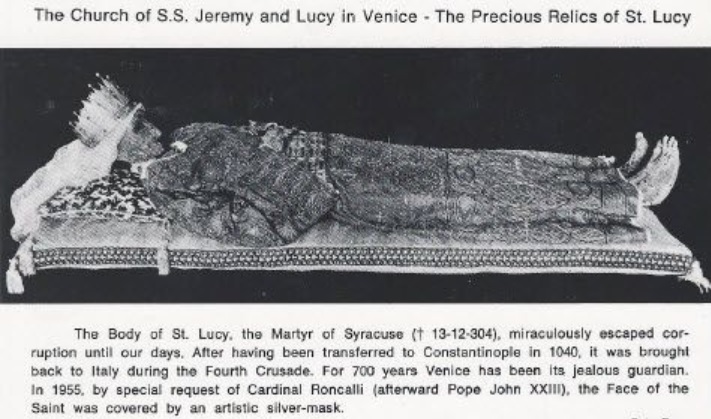

Many of the incorrupt bodies of Catholic saints are actually mummies. That’s not to say that they were embalmed at the time of death in accord with the ancient pagan Egyptian practice; rather, environmental conditions where they were buried resulted in their bodies being dried and preserved naturally. A good example of this is the martyr Saint Lucy, who was killed in the year 304 and is now preserved in a glass casket in Venice, Italy. Any visitor to her shrine can see clearly that Lucy is anything but incorrupt—on the contrary, her grotesquely shriveled and shrunken brown body resembles the Egyptian mummies just mentioned. Yes, there is ample historical evidence that Lucy lived a Christian life and died a martyr’s death, bravely and heroically, and that is what prompted the Church to venerate her as a saint almost immediately after she died. The condition of her physical remains had no bearing whatsoever on the Church’s inclusion of Lucy’s name on the roster of the saints.

Fast-forward nearly 1000 years and you will encounter Saint Zita (d. 1272). A simple domestic servant in the Italian city of Lucca, Zita became known during her lifetime for her charity toward those who were even poorer than she was. She was venerated by the faithful already long before her tomb was opened in the 16th century, at which point her body was found intact.

Is Zita’s body “miraculously incorrupt”? If you visit her tomb in Lucca today, you’ll see  that while she’s in much better shape than Saint Lucy, Zita too appears to be mummified. Note that the Church has not made any sort of official statement asserting that the condition of Saint Zita’s remains is scientifically inexplicable, and thus must be considered miraculous. And since there is no indication that the Archbishop of Lucca is planning to have Zita’s body scientifically examined any time soon, this question must be left unanswered.

that while she’s in much better shape than Saint Lucy, Zita too appears to be mummified. Note that the Church has not made any sort of official statement asserting that the condition of Saint Zita’s remains is scientifically inexplicable, and thus must be considered miraculous. And since there is no indication that the Archbishop of Lucca is planning to have Zita’s body scientifically examined any time soon, this question must be left unanswered.

A relatively more recent, and more puzzling case is that of the Polish martyr Saint Andrew Bobola. This Jesuit priest was tortured extensively and partially flayed, before finally being killed by Cossacks in 1657. Despite its severely mutilated state, which if anything should have hastened its decomposition, his body was discovered to be completely incorrupt when it was exhumed in the 1700’s.

Thanks to the redrawing of national borders, St. Andrew Bobola’s body ended up in Moscow after the Bolshevik Revolution, where a team of Communist party officials, scientists, and other important personages formally inspected his body. They declared that it had mummified naturally, due to favorable conditions of the soil in which his coffin had been buried. But as we can all surely appreciate, the officially atheist Soviet government had no intention of publicly admitting that anything had ever happened as a result of divine intervention—so the report of this investigation can hardly be accepted at face value. Until a new and truly objective team of genuine scientists conducts an impartial examination of his body, we cannot be sure whether Andrew Bobola’s body is miraculously incorrupt or not. What we do know, however, is that the arguably incorrupt state of his physical remains had absolutely no influence on his canonization as a martyr-saint. What did prompt the Church first to beatify, and then canonize Andrew Bobola in 1938 were the nearly two dozen medically unexplained healings of seriously ill people through his intercession.

A fair number of canonized saints were found to be incorrupt when their bodies were exhumed after their death—but when they were reburied, and subsequently unearthed again at a much later date, their remains were found to have decayed naturally. Saints Pierre Julian Eymard and Francis de Sales are good examples of this. Was the first discovery of incorruption a miracle, or not? At this point, it’s impossible to know.

At the same time, plenty of saints are popularly believed to be “incorrupt” today, when in fact they most certainly are not. Saint Pio of Pietrelcina is a good example of this, as is Pope Saint John XXIII. Saint Angela of Foligno (seen here) is repeatedly reported to be incorrupt by credulous Catholics, who fail to understand that like many other saints, her remains are

At the same time, plenty of saints are popularly believed to be “incorrupt” today, when in fact they most certainly are not. Saint Pio of Pietrelcina is a good example of this, as is Pope Saint John XXIII. Saint Angela of Foligno (seen here) is repeatedly reported to be incorrupt by credulous Catholics, who fail to understand that like many other saints, her remains are encased in a sculpture! And for some reason stories persist that Saint Catherine of Siena (d. 1380) is incorrupt—despite the fact that her mummified head is in Siena, one mummified foot (seen here) is in Venice, and most of the rest of her is still in Rome where she died.

encased in a sculpture! And for some reason stories persist that Saint Catherine of Siena (d. 1380) is incorrupt—despite the fact that her mummified head is in Siena, one mummified foot (seen here) is in Venice, and most of the rest of her is still in Rome where she died.

Confusing matters even further, it is well known that when bodies of holy persons do appear to be miraculously incorrupt, in an amazing number of instances the living have deliberately tampered with them. Saint Bernadette of Lourdes (d. 1879), for example, was beautifully preserved for many years after her death and burial … until the sisters of her convent decided on their own to give her a good washing. The body of Saint Francis Xavier (d. 1552) was exhumed at the time of his beatification and found to be incorrupt; it understandably wouldn’t fit into the small box intended to house his bones under an altar—but they forcibly stuffed him into that container anyway, breaking his neck in the process. (Is he still incorrupt today? Have a look and decide for yourself.) And after his death in 1914, Pope Pius X’s body was initially said to be inexplicably incorrupt until someone in the Vatican injected it with chemicals, whereupon it noticeably changed and is now a very non-miraculous mummy. Sometimes, you can’t help but wonder why God would even bother to miraculously preserve the bodies of His saints, since we plainly don’t know how to take care of them.

But do we ever encounter cases where someone who is definitely not a saint has died, and later been found to be “incorrupt”? Absolutely! Here is a tragic example of Yvette Vickers, a former Playboy model and Hollywood actress, who died all alone in her home sometime in 2010, and wasn’t discovered for about a year. Her body was found mummified in her bed—a totally natural result of the atmospheric conditions inside her house. Without being judgmental, we may safely presume that nobody is planning to canonize her as a saint. (In fact, let’s all say a quick prayer for this woman right now.) A different, eerie situation involving a non-saint is that of the so-called “Soapman,” an unknown man whose body was discovered in Philadelphia in 1875: as the scientists put it,

This unusual preservation occurred because water seeped into the casket and brought alkaline soil with it, turning the fats in his body to soap through a type of hydrolysis known as saponification.

By now, the takeaway should be this: when someone’s body seems unusually well preserved after death, it’s definitely worth a closer look—but prudence dictates that Catholics should be extremely cautious about jumping to conclusions regarding the miraculous nature of the preservation, or that person’s holiness. The “bunch of woman at our parish” whom Craig describes should take note.

With all this in mind, let’s now turn to the case of the late Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster, the foundress of a Benedictine monastery in Missouri, who died in 2019 and was buried without embalming. She was recently exhumed, not as part of any canonization process, but simply because the sisters of her monastery had been planning the construction of a new shrine to Saint Joseph where (among other things) Sister Wilhelmina was to be reinterred. The discovery that her body is remarkably well preserved was thus a complete accident.

Those who knew her all attest that she led an exemplary life, something which is incontestable regardless of whether her body is in fact miraculously incorrupt or not! If her cause for canonization is someday opened, the physical condition of her remains will not be a factor in the Church’s decision in her case. Nevertheless, readers have likely heard the Fake News breathlessly declaiming that “A nun has moved one step closer to sainthood after her exhumed body showed no signs of decay, four years after it was buried,” and calling it “a miracle in Missouri.”

Ironically, perhaps the most level-headed, rational response to this discovery has been that of the nuns in Sister Wilhelmina’s abbey (see “What’s the Difference Between Sisters and Nuns?” for more on what a nun is). Their official statement calmly explains why their foundress was disinterred in the first place—and tactfully observes that the nuns had intended to keep this discovery quiet, but “unfortunately, a private email was posted publicly, and the news began to spread like wildfire.”

And as for canonizing Sister Wilhelmina, the nuns of her abbey hit the nail on the head when they point out,

The relics of a person are exhumed in the ordinary course of action for the opening of the causes of saints, leading many to believe that such a cause has been or will be opened. As this is not the case, we continue on with a simple reinterment of our foundress, and are seeking advice on a possible opening of a cause in the future, especially as Sister has not yet reached the required minimum of five years since death in order to begin (emphasis added).

The fact is, the current norms governing the process of canonization of saints state clearly that “In recent causes, the petition must be presented no sooner than five years after the death of the Servant of God” (9a). Since Sister Wilhelmina died in 2019, any initial petition for her canonization can’t be made until at least 2024! (Is that “bunch of women from our parish” paying attention?) Yes, it is possible for the Pope to waive the five-year waiting period, as Benedict XVI did for the cause of Pope John Paul II; but the Benedictine nuns of Sister Wilhelmina’s abbey haven’t even requested this—and even if they did, the mere claim that her body is “miraculously incorrupt” would not constitute any justification for doing this. As the nuns explain so patiently in their official statement,

While we can attest to Sister’s personal sanctity, we know that incorruptibility is not among the official signs taken by the Church as a miracle for sainthood, and that all things must be subjected to further scrutiny, especially by the competent authorities in the medical field. The life itself and favors received must be established as proof of holiness.

In short, Sister Wilhelmina may very well be a saint, and who knows, perhaps God is drawing our attention to that fact through supernatural means! But if that’s the case, it might be far better to respond by prayerfully examining the holy life of this nun, and aiming to imitate her virtues as best we can—rather than “pontificating on her sainthood and … preparing verbal attacks on the Vatican and the Pope himself,” as the women of Craig’s parish are doing. Before launching criticism at church officials because they fail to do what we want, let’s first be sure that what we want is theologically sound, and in accord with the laws of the Church.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.