Q: As for religious order priests or bishops, who normally take the three traditional vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, how does ordination to the episcopate change the requirement that they observe their vows? E.g., a Franciscan who is vowed to poverty suddenly becoming a bishop with the usual perquisites such as a salary, nicer living accommodations, driver, etc.? Unlike a diocesan priest, this would seem to be a contradiction to the life of poverty/simplicity implicit in their initial profession. –Daniel

A: Daniel seems to be onto something, doesn’t he? There certainly does appear to be an inherent contradiction between being a member of a religious institute, and being a bishop—and yet there are plenty of clergy (including Pope Francis, a Jesuit) who somehow are both at the same time. Let’s take a look at what elements can potentially conflict, when a priest who has vowed the evangelical counsels of poverty, chastity, and obedience is named a bishop. Then we can examine how the Code of Canon Law manages to make this apparent conflict work.

As was discussed in “Bishops, Archbishops, and Cardinals,” bishops/archbishops are priests who are selected by the Pope to become bishops, which is effected through a sacramental consecration (cf. c. 375). Most bishops are diocesan bishops, who are put in charge of dioceses; while there are others who are called to work in high-ranking positions in the Vatican, and are known as titular bishops (c. 376).

Before being chosen to be bishops, these men were already ordained priests, of course—and as most of us probably know, some (but not all) priests also happen to be members of religious institutes, such as the Benedictines and Jesuits. Maybe these priests are involved in parish ministry within a diocese somewhere, and maybe they’re not: they could very well be university professors, or doctors working in missionary territory, or contemplatives who spend a great part of their day praying inside a monastery, Many (but not all) religious institutes require their members to take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience (cf. c. 573.2). This was discussed at length in “The Priesthood and the Vow of Poverty.”

If a Catholic priest isn’t a member of a religious institute, you may reasonably conclude that he’s a diocesan priest, who was ordained to minister to the faithful of the diocese. In contrast to the religious priests mentioned above, diocesan priests do not take vows, and thus are not required to embrace poverty.

In short, some priests vow poverty, while others do not. In terms of everyday life, the vow of poverty (or lack thereof) can amount to an enormous distinction between these two groupings of priests. The Pope can, however, select a priest from either category to be a bishop, and bishops are not required to live in poverty at all. Canon 387 tells us that a diocesan bishop is to be mindful of his obligation to show an example of holiness in charity, humility, and simplicity of life; but “simplicity of life” is not synonymous with “poverty.” (True, there have unfortunately been some bishops out there in recent years who inexplicably decided that they could live like royalty at their diocese’s expense—but as we saw in “Canon Law and Bishops of Bling,” this has rightly been called out for the scandalous conduct that it is, and the Pope himself has been known to directly intervene to put a stop to it.)

Daniel does indeed have a point that when a priest who has vowed poverty becomes a bishop, “this would seem to be a contradiction to the life of poverty/simplicity implicit in their initial profession.” So what happens when a priest who made a vow of poverty—a Franciscan, for example—is chosen to become a diocesan bishop?

Conveniently, the Code of Canon Law provides a clear answer to this question. Its section dealing with religious institutes contains a small chapter which is dedicated entirely to “religious who are elevated to the episcopate” (cc. 705-707).

Living a life of poverty (or not) isn’t the only issue that arises in such a scenario. Another question centers on the vow of obedience. After all, if a man has vowed obedience to his superiors in, say, the Dominican order, what authority do those superiors retain over him once he’s become a bishop? Canon 705 resolves any possible confusion about this, stating that the religious-turned-bishop remains a member of his institute, but now is subject only to the Pope as his superior. In terms of Catholic ecclesiology, this is as it should be: in the Church’s hierarchy the bishop is ranked immediately below the Pope, and the fact that some bishops are also members of institutes like the Dominicans or Franciscans doesn’t change that.

The same canon 705 contains another sentence which is directly relevant to Daniel’s question, even though it is couched in generic terms: a religious who has become a bishop is not bound by obligations which he prudently judges are not compatible with his condition as a bishop. Daniel is right that normally a diocesan bishop lives in the bishop’s residence, may have a car with a driver, might travel to conferences and stay in hotels, etc. … and while these sorts of things could conflict with a life of poverty, they may be perfectly consistent with the life of a bishop. As a general rule, the religious-turned-bishop now lives not as a religious in poverty, but as a bishop. This assumes, of course, that a bishop is always following the abovementioned canon 387, and showing the faithful an example of “simplicity of life” even though it’s not a life of actual poverty.

The following canon 706 provides a series of rules about the ownership of property by religious who have become bishops. This canon can get a bit confusing if you’re unaware that different religious institutes have different rules about the ownership and administration of personal property. For example, members of some (but not all) religious institutes are required to renounce the ownership of all goods: any property that they might own before becoming members must be given to somebody else, and once they become members the property they subsequently earn or are given along the way belongs not to them personally, but to the institute (cf. c. 668.4 and .5). If a bishop is a member of an institute with such rules, canon 706 n. 1 tells us that now he can personally use and enjoy anything he may acquire as a bishop—such as a car, for instance. But technically, he still doesn’t own such things; they actually belong to either the diocese (if he’s a diocesan bishop) or to the Holy See (if he’s a titular bishop).

In contrast, there are other religious institutes in the Church which allow all their members to continue to own property, but they must cede the administration of it to someone else before they enter the institute. So, for example, if an incoming member of such an institute already owns shares of stock in a company, he can continue to own them—but as a religious he cannot be buying/selling them, re-investing his dividends, etc. This sort of activity has to be entrusted in advance to somebody else (c. 668.1). If a bishop happens to be a member of a religious institute with this rule, his situation falls under canon 706 n. 2. This canon says that now, as a bishop, he recovers the use and administration of the goods he owned before becoming a religious—and he owns outright anything he may acquire as bishop.

Regardless of which type of rules his religious institute has for the use and administration of property, there’s one important takeaway here that’s worth a mention. It is clear from canon 706 that a when a religious becomes a bishop, his religious institute has no claim on any of his material goods.

The final canon in this little chapter has to do with a religious-turned-bishop after his retirement. Ordinarily, members of religious institutes receive whatever they reasonably need from their institutes (cf. c. 670), which logically means that when they are elderly and no longer working, the institute continues to take care of their needs. And remember, religious who become bishops are still members of their institutes, as we saw above. So who’s expected to pay for the needs of a religious-turned-bishop once he’s retired: his religious institute, or his diocese?

Canon 707.2 has the answer. Support for a retired bishop who is a member of a religious institute is the responsibility of his diocese/episcopal conference, just like any other diocesan bishop. It makes reference to canon 402.2, which notes that bishops’ conferences are obliged to ensure that their retired bishops are cared for (see “Are Catholics Supposed to Abstain from Meat Every Friday?” for more on what a bishops’ conference is), although the primary obligation rests with the bishop’s own diocese.

When members of religious institutes retire, they still must live within a house of their institute; but if a religious has become a bishop, canon 707.1 states that he is not required to do this unless his superior, the Pope, decides otherwise. Note that a retired bishop who is a religious certainly can retire to a house of his own institute, if he wishes; he is, after all, still a member of the institute.

While we’re on the subject, how often does it happen that a Pope selects a member of a  religious institute to become a bishop? Here’s a handy chart showing the current number of living bishops (in the far right column) who are also religious. As can be seen, there are several hundred of them around the world today.

religious institute to become a bishop? Here’s a handy chart showing the current number of living bishops (in the far right column) who are also religious. As can be seen, there are several hundred of them around the world today.

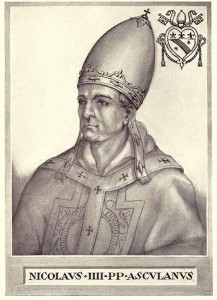

And by the way, there’s nothing new about this practice: for example, Franciscan Father Girolamo Masci was consecrated a bishop and later elected Pope Nicholas IV in 1288, just a few decades after St. Francis of Assisi had founded the Franciscans. And a couple of centuries later, Antonio Ghislieri was a Dominican priest who was made a bishop in 1556, only to become Pope Pius V a decade later. Not every religious who becomes a bishop  will end up becoming Pope, of course! But these two are among the more well known examples of religious who had vowed poverty, chastity and obedience, and later involuntarily found themselves living a very different sort of clerical life. Sometimes the mere fact that a man has voluntarily decided to take such vows can lead Rome to conclude that he’s not ambitious or power-hungry—and that can make him an attractive candidate for the episcopacy. The end-result is that paradoxically, a priest who’s a member of a religious institute can potentially be handed some of the very things which he freely chose to forego for the rest of his life.

will end up becoming Pope, of course! But these two are among the more well known examples of religious who had vowed poverty, chastity and obedience, and later involuntarily found themselves living a very different sort of clerical life. Sometimes the mere fact that a man has voluntarily decided to take such vows can lead Rome to conclude that he’s not ambitious or power-hungry—and that can make him an attractive candidate for the episcopacy. The end-result is that paradoxically, a priest who’s a member of a religious institute can potentially be handed some of the very things which he freely chose to forego for the rest of his life.

Ideally, the Church wants to select the best possible men for the job, and often it is judged that the best priests for the episcopacy are members of religious institutes. While there definitely does seem to be a contradiction between life as a religious, and life as a bishop, the Church has established rules to live by, enabling a priest who falls into both categories to do just that.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.