Q1: I have a question after your article “Canon Law and the Private Ownership of Relics, Part I” was shared with me.

A few weeks ago, I was in Rome on pilgrimage. I received from a Passionist priest at a monastery there a first-class relic of St. Gemma Galgani, a saint I dearly love. It came at no cost and with an official certificate from their postulator general.

But yesterday another priest informed me that there are directives from the Holy See and canon law discouraging the private ownership of first-class relics; he said that he and others received first-class relics from the same location, but they were taken by the ordinary bishop of a neighboring diocese once the bishop broke the news regarding private ownership of relics.

I was very surprised to have heard this. The relic was given to me by a priest of the congregation, and it seemed like a very common practice of the Passionist monastery…

As I devout Catholic, I want to do right by God and Holy Mother Church. Your article says that today it is not possible to legally obtain first-class relics from Rome on a personal basis, so I am concerned with the idea that I very innocently but illegally obtained and now possess a first-class relic. Does it seem like this monastery has the legal right to distribute such relics of saints associated with their congregation, or is it an abuse? Why does it seem like few priests are aware of these directives? What should I do? –Phil

Q2: In this article, you spoke of a parish priest petitioning Rome for the relics of a saint to be placed in the altar of a parish church.

I’m interested in knowing if there is anything in canon law regarding other custodians of relics— not the Vatican, but, for example, the religious order to which a saint belonged. Are there any rules or laws governing how a religious order, for example, acts as custodian of the relics of a saint who belonged to their order?

In the parish where I work in [Europe], we have a number of relics…. Often we get email requests, always from other countries, for us to “send a relic” to a person by mail. Once an American woman even sent an email telling us when she’d appear in our city and asking where, exactly, she “should go to pick up my relic” of a certain saint. She expected just to appear and walk away with a first-class relic.

Even the clergy can be clueless about “what you have to do to get a first-class relic.” I could not imagine that a parish priest would not realize that an American vacationing in Europe cannot just walk into a local parish and “pick up a relic” like a souvenir t-shirt or coffee mug… –Cornelia

A: It’s bewildering to hear constantly of such confusion regarding the ownership of relics of the saints, because as was seen in the article cited in both of these questions, the general rules are not all that complicated. And even though our questioners come from opposite ends of the globe, they both note that even the clergy often misunderstood what is—and what isn’t—permitted regarding both the transfer and the ownership of relics. Perhaps it’s fortuitous, then, that the Vatican issued a new Instruction on this topic just a few months ago, complementing existing laws on the subject. Let’s take another look at this issue in more detail, and also see what the new Vatican document has to say about it.

In “Part I,” we saw that the Church’s strictest rules pertain to first-class relics, a category which includes parts of the bodies of the saints (normally bones, hair, or teeth), as well as other items central to our faith, like the wood of Christ’s Cross. Christians have been venerating the relics of the saints ever since the earliest days of the Church, when Christian women like the Roman St. Praxedes carefully collected the mutilated remains of the martyrs from the arenas where they had been killed, and saved them as something precious. There is plenty of historical evidence that the early Christians instinctively venerated the blood that was shed by their fellow-believers, who continued to proclaim their faith in Christ even if this would ultimately cost them their lives. So there is nothing new about all this.

We also saw in “Part I” that in centuries past, it was extremely common for Catholics to seek to obtain relics of all sorts of saints, and for this reason there are many thousands of relics still owned by private individuals today. But “Part I” noted that nowadays, the Church prefers that relics of saints be not in private hands, but rather in a public church or chapel where they can be venerated by all the faithful. That’s why, if an ordinary Catholic were now to contact the Sacrario Apostolico in Rome and request a saint’s relic for himself, the Vatican would decline.

But as Cornelia rightly points out, there are many, many saints around the world whose remains are in the custody not of the Vatican, but of Catholic dioceses or religious institutes. To take an obvious example, Saint Teresa of Calcutta is, unsurprisingly, entombed in the motherhouse of the Missionaries of Charity in Calcutta. The tomb of Saint John Vianney, who was a French diocesan priest from the city of Ars, is today in a shrine in the diocese of Belley-Ars. Such places are of course Catholic, and thus are ultimately under the authority of Rome like all Catholic entities; but they are not under the direct supervision of the Vatican. So what happens if someone wants a relic of a saint who is buried in a place like this?

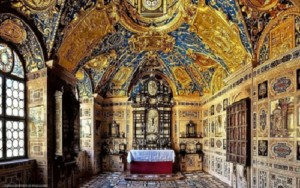

Unfortunately, in centuries gone by, the success of your request frequently depended in practice on how powerful and important you were. If, let’s say, a medieval bishop or a prince were to ask the Abbot of a monastery for a large bone from the tomb of some saint who was buried there, the odds were much higher that he would get what he wanted (perhaps after threats and arm-twisting?), than if some poor devout peasant girl were to make the same request. This was simply the way that western Europe’s class-structured society used to work. It explains why one can still find extensive collections of saints’  relics in many castles, palaces and monastery chapels throughout Europe today. Munich’s Residenz palace, built by the royal Wittelsbach family of Bavaria, still houses an enormous collection of relics that is particularly impressive.

relics in many castles, palaces and monastery chapels throughout Europe today. Munich’s Residenz palace, built by the royal Wittelsbach family of Bavaria, still houses an enormous collection of relics that is particularly impressive.

Note that in centuries-old relic-collections like that of the Residenz, the relics are often a lot more substantial than just a tiny chip of bone or clip of hair. The collection often includes entire skulls, long leg-bones and other large pieces of saints’ bodies. (The significance of this fact will become evident in a moment.) Since places like the Residenz were homes of royals, and their chapels were not routinely open to the public, the relics they contain could only be viewed and venerated by the privileged few who were permitted to enter. This meant, of course, that some major relics of major saints were accessible by certain members of the upper-class, but totally off-limits to the rest of the faithful.

This is not meant to disparage the royals and other important people who eagerly sought to obtain relics in order to devoutly venerate them. What they were doing was totally aboveboard at the time! But over the years, the Church has gradually tried to put the brakes on haphazard practices regarding the transfer of relics, especially to private persons. Rules which it makes today are intended to apply to everyone, thus making praxis as consistent as possible around the world.

New steps in this direction were taken only a few months ago by the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints, which issued an Instruction called Relics in the Church: Authenticity and Preservation. Much of this Instruction pertains specifically to bodies of persons whose beatification or canonization is currently in process, and so it is not directly relevant to our two questions here. But the Instruction does provide us with an important general distinction which ties into Phil’s question, between significant and non-significant relics:

The body of the Blesseds and of the Saints or notable parts of the bodies themselves or the sum total of the ashes obtained by their cremation are traditionally considered significant relics. Diocesan Bishops, Eparchs, those equivalent to them in law and the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints reserve for these relics a special care and vigilance in order to assure their preservation and veneration and to avoid abuses. They are, therefore, preserved in properly sealed urns and are kept in places that guarantee their safety, respect their sacredness and encourage their cult.

Little fragments of the body of the Blesseds and of the Saints…are considered non-significant relics. If possible, they must be preserved in sealed cases. They are, however, preserved and honored with a religious spirit, avoiding every type of superstition and illicit trade. (Introduction)

As can be seen here, it’s one thing to have an entire body of a saint, his skull, large bones or a large number of bones, etc.; and quite another to possess a little reliquary containing an almost microscopic fragment. It makes perfect sense for the Church to seek to ensure that large, significant relics are not given willy-nilly to private individuals for personal devotion—but the strict rules requiring hierarchical approval of the transfer of large relics do not apply (and never have!) to those teeny decomposed bits that are often found at the bottom of saints’ tombs when they are opened many years after death. We can see from the Instruction that these non-significant first-class relics are of course not to be treated with disdain—they are first-class relics, no matter their size—but giving them to pious persons is not prohibited, and it certainly does not require the official permission and formal authentication that is mandated for bigger ones.

With that in mind, let’s look at Phil’s situation. St. Gemma Galgani (d. 1903) was an Italian mystic, whose tomb is in the Passionist monastery in the city of Lucca. Obviously, therefore, the Passionist Fathers have custody of her remains, which makes perfect sense because she was closely affiliated with the Passionists during her life. If, therefore, a member of the Passionists wants to give Phil a small reliquary with a tiny non-significant relic of St. Gemma—and the priest didn’t steal it, and he is not disobeying his superiors by giving it away—then he is perfectly free to do just that!

That’s why it is utterly mystifying to hear of the other incident Phil describes, in which a Catholic bishop heard that some other individual had obtained just such a relic, and took it away from him because he wasn’t supposed to have it. To be fair, we don’t know the details; but it sounds like a member of the Catholic hierarchy wrongly decided that something improper had occurred, and “corrected” the imaginary problem by taking the relic himself. If that’s the case—and it’s important to remember that there may be a lot more to this that we don’t know—then the bishop essentially stole a person’s private property, and needless to say he must give it back.

Even if the relic, which this bishop allegedly arrogated to himself, had indeed been wrongly given to the individual who had it… taking it away for one’s own diocese is hardly the correct way to right a wrong. If, for the sake of argument, some Passionist had improperly given away a relic of St. Gemma when he had no right to do so, then the just thing to do is to notify that Passionist’s superiors of the wrongdoing, and to return the relic to the Passionist monastery where it came from! Let’s hope that there is more to the story, and that the bishop whom Phil describes didn’t simply steal a relic which rightly belongs to someone else.

And speaking of private property which rightly belongs to someone else, it’s quite difficult to fathom the scenario which Cornelia describes, concerning the crass American woman who announced (not asked!) that she would come to get a relic of a saint in Cornelia’s parish. Nobody has a right to a relic of a saint, and it’s pretty shocking to hear that there are Catholics out there who fail to understand this. Imagine that a stranger contacted you and declared that he/she would be in your town next week, and wanted to stop by and pick up one of your teacups! The relics of a saint are likewise private property and at a bare minimum, it’s extremely rude to think that one can simply show up and take one.

In conjunction with the information on this subject contained in “Part I,” let’s now try to sum up what generally can and can’t be done, with regard to relics:

1. As per canon 1190.1, no relics can ever be bought or sold. Period.

2. If a relic is already in a place where it is being venerated by the faithful, it cannot be permanently removed from that location and taken to another, without Rome’s permission (c. 1190.2). For example, if the Franciscans and the Bishop of Assisi decided to move the tomb of St. Francis from his basilica in Assisi to another location (which of course they have absolutely no plans to do!), they would first need to get approval from the Vatican. That’s because the tomb of St. Francis in his basilica in Assisi has been a major pilgrimage site for centuries, and moving his tomb elsewhere would obliterate that.

But note that it would be different if the Franciscans merely wanted to give a bone from Francis’ tomb to (let’s say) a parish church run by Franciscans in Mexico, for veneration by the faithful there. In that case, no permission from Rome would normally be necessary—because it would not alter the fact that St. Francis is, for the most part, still buried in the crypt of his basilica in Assisi. His remains would still be venerated there, even if a little part of them was sent elsewhere. While this example is wholly imaginary, in practice this sort of thing happens all the time.

3. Anybody—whether an individual who wants a non-significant relic for personal devotion, or a diocesan bishop, a monastery, or some other Catholic entity that wishes to erect a shrine or consecrate an altar—might request a particular saint’s relic(s) from whomever has custody of them… but the custodian of the relics has, strictly speaking, no obligation to grant the specific request. To cite an extreme example, the tomb of St. Paul  the Apostle here in Rome hasn’t been opened in at least 1700 years. It is in the care of Benedictine monks; but since it is housed in a papal basilica, only the Pope himself could grant permission for the tomb to be opened. Because of the way the sarcophagus is wedged into the crypt underneath tons of bricks and stone beneath the main altar, it would require a massive construction project just to get it out—and no Pope has ever allowed this to be done. For this reason anyone (no matter how prestigious!) who wants a relic of St. Paul can basically forget it.

the Apostle here in Rome hasn’t been opened in at least 1700 years. It is in the care of Benedictine monks; but since it is housed in a papal basilica, only the Pope himself could grant permission for the tomb to be opened. Because of the way the sarcophagus is wedged into the crypt underneath tons of bricks and stone beneath the main altar, it would require a massive construction project just to get it out—and no Pope has ever allowed this to be done. For this reason anyone (no matter how prestigious!) who wants a relic of St. Paul can basically forget it.

It is true that technically, if the relics of a saint are in the custody of a diocese or a religious institute, the Vatican could always order them to open the tomb and give a relic(s) to someone, and as Catholics they would be obliged to obey even if they were otherwise opposed to the idea. But such an order would be indicative of a highly unusual and probably very contentious situation, as this isn’t normally how it works.

Thus officials at Cornelia’s church could give a non-significant relic of their saint to a private individual (even a rude American!), if they had one available, and if they chose to do so—but they certainly don’t have to. It wouldn’t reflect much respect for the saint’s relics if the parish randomly handed them out to everyone; and it’s equally disrespectful for any Catholic to expect them to do just that.

4. If the owner (whether a private individual, or a religious order, or some other Catholic official or entity) of a small, non-significant relic of a saint wishes to give it to someone, he/she is free to do so, provided that it seems clear that the relic will be treated with respect and devotion. It’s important to remember that relics are not like baseball cards or postage stamps, to be collected and traded just for fun.

Perhaps now the rules regarding the relics of saints are a bit clearer. Both Phil and Cornelia can rest easy, because in each case, they are in the right. It’s totally okay for an individual Catholic to be given a non-significant relic of a saint, for private devotion; but Catholics shouldn’t think they can demand them and automatically get them.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.