Q: I read in a news article that Pope Benedict said he would resign, if he reached the point where he couldn’t physically handle being Pope any longer. Is that even possible? Can a Pope ever resign? —Scott

A: It’s true that in the nearly eight years of Pope Benedict’s reign, more than one news article has been written on this subject. It’s of particularly keen interest to those opposed to his teachings, who would gladly see him leave the Throne of Peter as soon as possible—but it’s of interest to many of the rest of us as well, if only as a matter of curiosity. Can Benedict XVI, or any future Pope, resign if he wants to?

Only one canon of the entire Code of Canon Law makes any mention of this. Canon 332.2 states that if it happens that the Roman Pontiff resigns from his office, it is required for validity that his resignation be freely made and properly manifested, but it isn’t necessary that it be accepted by anyone. At first glance, it may strike readers as a rather odd thing to say at all! But when it’s read in the context of the entire Code of Canon Law and viewed in light of Catholic ecclesiology, it makes perfect sense. After all, the Pope is a bishop, the Bishop of Rome.

As was discussed in “Bishops, Archbishops, and Cardinals,” the Second Vatican Council taught clearly that episcopal consecration contains “the fullness of the sacrament of Orders” (LG 21). In other words, when the Pope decides that a particular priest is to become a bishop, that priest must be consecrated a bishop in the sacramental sense. But when a bishop is named a cardinal, and when a cardinal is elected Pope, there is no additional sacramental consecration of any kind. As canon 332.1 notes, the Roman Pontiff acquires full and supreme power in the Church when he has been lawfully elected and has accepted his election. This means that at the very moment when Cardinal Ratzinger, sitting in the Sistine Chapel among his fellow cardinals during the 2005 conclave, was asked to accept his election as Pope and agreed, he was Pope! While there subsequently were some “official” ceremonies, including an announcement from the Loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica that “Habemus Papam, we have a Pope!” as well as an open-air Mass in St. Peter’s Square, these were merely formalities, and were not required for Pope Benedict to have full papal power.

Consequently, one could say that the Pope is a bishop who was elected by a group of bishops to be the Bishop of Rome. It’s only a matter of logic, then, that if a bishop can resign, the Pope ought to be able to resign too. Let’s take a look at what the law says about the resignation of more “typical” bishops, both those who head dioceses and those who work in the Vatican. Then the code’s solitary reference to papal resignation can be seen to fit neatly into the equation.

Canon 401.1 states that a diocesan bishop is asked to offer his resignation to the Supreme Pontiff, once that bishop has reached the age of 75. The following paragraph adds that a younger diocesan bishop, who has become unsuited for fulfillment of his office due to illness or other grave reasons, is earnestly requested to offer his resignation as well (c. 401.2). Note, however, that the Pope doesn’t have to accept the resignation—which is why one frequently encounters bishops who are still ruling their dioceses, months or even years later. Sometimes a bishop remains longer in office because the Pope is still searching for a suitable replacement. In other cases, the 75-year-old bishop is in good health, and (in the Pope’s opinion) is doing a satisfactory job in his diocese, so there is simply no reason to remove him yet. John Cardinal O’Connor, for example, served as the Archbishop of New York until his death in 2000 at the age of 80. He had submitted his resignation five years earlier to Pope John Paul II, but the Pope preferred to leave Cardinal O’Connor in office. This was widely viewed as a public sign of the Pope’s approval of O’Connor’s leadership.

The case of a bishop working in the Vatican Curia is similar. Those bishops who head the various Congregations are known as prefects, and are always cardinals. (Again, the distinction between bishops and cardinals was discussed in a previous column, “Bishops, Archbishops, and Cardinals.”) The law pertaining to their resignation is found in both the code and also the Apostolic Constitution Pastor Bonus, which is a document promulgated by Pope John Paul II in 1988, outlining the structure of the Vatican offices. Both canon 354 and PB 5.2 say the same thing: when these cardinals reach their 75th birthday, they are asked to offer their resignations to the Supreme Pontiff, who will provide accordingly. (The same section of PB also addresses those bishops who work in the Vatican but are not cardinals: in their case, when they turn 75, their office simply ceases.)

We can see that even if a bishop is anxious to resign his office, he can’t walk away from his duties until the Pope accepts his resignation. But what happens if the one who wants to resign is the Pope himself? This is where the specific wording of the abovementioned canon 332.2 becomes clear. If the Pope wants to resign, nobody has to accept his resignation. He would not be obliged to wait until somebody else agreed to it! Since the Pope has supreme authority in the Church (cf. c. 331), this makes complete sense. Nobody on earth has power over the Supreme Pontiff, which means that nobody else could block his resignation, if ever and whenever he wanted to do it.

Note that the same canon 332.2 also states that for a Pope to resign, his decision must be freely made. In other words, he must understand what he is doing, and nobody else can either force or trick him into doing it. This is completely consistent with the code’s requirements for resignation from an ecclesiastical office in general. Canon 187 gives us the norm, using a Latin expression that’s difficult to translate: anybody can resign from any ecclesiastical office for a just reason, so long as he is sui compos. A person who is considered sui compos has the ability to think for himself, and make responsible choices using his own mental power. Someone who is mentally disabled, unconscious, insane, or suffering from dementia is not considered sui compos, because he is unable to rationalize what he is doing, and to take responsibility for his actions. Clearly, then, if the Pope were unable for any reason to make a rational decision on his own, he could not make the decision to resign.

The very next canon talks about external forces being brought to bear on a person who resigns his office. Canon 188 observes that a resignation is invalid if it is made because of unjustly inflicted grave fear, deceit, substantial error, or simony. How would this panoply of situations apply to the Pope?

First of all, if someone were standing over the Pope with a gun, threatening to kill him if he didn’t resign, this would obviously constitute “unjustly inflicted grave fear,” and would invalidate any decision by the Pope to acquiesce. Or if the Pope were somehow tricked into signing a letter of resignation—by someone who (let’s say) hurriedly asked him to sign a document without reading it, assuring him that the paper really concerned some other matter—the signed document would have no legal force by virtue of the deceit involved.

“Substantial error” is harder to envision in the case of a papal resignation. Such error can theoretically occur if the person holding an ecclesiastical office incorrectly thinks that (for example) he is required to submit his resignation after holding it for a certain number of years, or when his superior dies and is replaced by someone else. A resignation that is made as the result of such a misunderstanding is invalid under canon 188. When it comes to the Pope, who knows full well that his office is intended to last until his death, it is difficult to imagine that he could make such a mistake!

The last scenario addressed by canon 188 involves simony, which is the selling of an office for money. Since an ecclesiastical office cannot validly be bought or sold (c. 149.3), it only follows that a resignation from such an office cannot validly be purchased either! It’s pretty difficult to envision that a Pope would decide to resign in exchange for a sum of money; but even if the Church were ever ruled by such a Pope, his resignation would be invalid ipso iure in any case.

In short, if a Pope wanted to resign, his decision would have to be fully free. He would have to understand what he was doing, and do it deliberately and willingly, without anyone else forcing him to act against his will. Readers who are familiar with the fundamental concepts of moral theology will appreciate that the law is simply ensuring that the Pope is responsible—culpable, if you like—for his action.

We can now see all that canon 332.2’s phrase “freely made” entails. But there is definite uncertainty about the exact meaning of another phrase of canon 332.2 which asserts that a Pope’s resignation has to be “properly manifested.” Would the Pope have to announce it in the presence of the College of Cardinals, for example? Nobody really knows—but since the Pope is the Church’s Supreme Legislator, he can interpret this law however he wishes. In the end, therefore, it wouldn’t really matter, so long as the Pope’s decision was expressed clearly, i.e., neither ambiguously nor secretly.

Now it should be plain what the law says, and why it says it. But let’s move from the world of abstract theory into that of concrete reality: would Pope Benedict XVI ever actually use it?

The media world seized on comments which the Pope made in a book-length interview published in 2010, which they reasonably interpreted as saying that he might. Pope Benedict told his interviewer that

…if a Pope clearly realizes that he is no longer physically, psychologically and spiritually capable of handling the duties of his office, then he has a right and, under some circumstances, also an obligation, to resign.

The Pope was, of course, speaking in a theoretical sense. There is nothing in his statement to suggest that he was/is seriously thinking about resigning himself. Still, the concept has been eagerly embraced by those who openly challenge both Catholic teachings, and the Pope who teaches them. Some have publicly declared that Pope Benedict should resign, because in their opinion, he did too little to combat clerical sexual abuse, and/or actually helped to cover it up. (Ironically, their “proof”of these grave accusations often involves the case of a now-deceased priest in Milwaukee, Wisconsin—a case which, as was discussed in “What Does it Mean to ‘Defrock’ a Priest?” most certainly did not involve any ‘cover-up’ by the former Cardinal Ratzinger.) It goes without saying that such temerity is, in and of itself, probably not going to influence any decision the Pope may make in this regard!

These sorts of calls for the Pope to resign are nothing new. The late Pope John Paul II faced them too, also from those hostile to the Church and her teachings.

It’s undeniable that Pope Benedict XVI is visibly suffering from the various physical infirmities that anyone approaching his 86th birthday can expect to face. Nevertheless, it is evident to all that his mind remains impressively sharp, and he is still obviously competent to do his job—whether people actually like what he does or not. There is absolutely nothing in his demeanor, his words, or his decisions that would suggest that (to use the Pope’s own words, already cited above) “he is no longer physically, psychologically and spiritually capable of handling the duties of his office.” On the contrary, Benedict’s stamina has been known to surprise those around him! There is no question that sometimes he is noticeably tired by the end of his public appearances and long meetings, but this hardly constitutes justification for a papal resignation.

Nonetheless, opponents of Pope Benedict continue to seek for an excuse to pressure him to resign. Even the “Vatileaks” incident (discussed in greater detail in “Canon Law and the Pope’s Butler”) was somehow seen by his foes as a reason for the Pope to step down from office. The logic of this assertion is difficult to ascertain. How could the treachery of a trusted employee be construed as a compelling justification for the resignation of his employer?

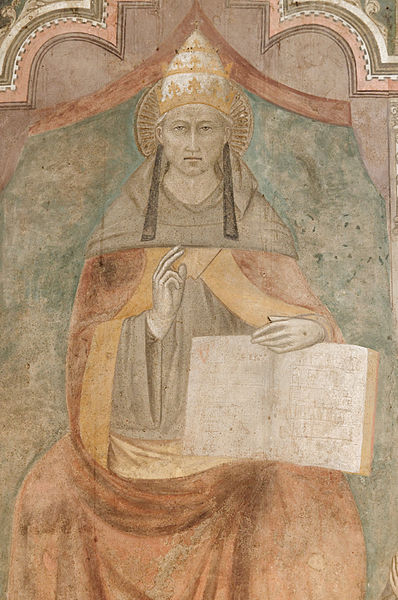

Benedict’s friends and enemies alike sometimes observe that there is historical precedent for a papal resignation, and technically, they’re right. Pope St. Celestine V resigned his office in 1294, and died less than two years later. The former Pietro Angelerio (also known as Pietro da Morrone) was a Benedictine monk who lived in a cave much like a hermit, and  he was chosen Pope as a compromise-solution to a desperate situation in the Church: cardinals had been wrangling over the selection of a new Pope for more than two years, during which time the See of Peter remained empty. Angelerio was summoned from his mountain-hermitage and initially refused to accept the office, with good reason—this simple ascetic, who was not himself a cardinal or even a bishop, had no experience whatsoever with the world of political intrigue in which the Popes of that era were immersed.

he was chosen Pope as a compromise-solution to a desperate situation in the Church: cardinals had been wrangling over the selection of a new Pope for more than two years, during which time the See of Peter remained empty. Angelerio was summoned from his mountain-hermitage and initially refused to accept the office, with good reason—this simple ascetic, who was not himself a cardinal or even a bishop, had no experience whatsoever with the world of political intrigue in which the Popes of that era were immersed.

Yielding to the cardinals’ insistence, the new Pope soon found himself, to put it simply, completely in over his head! While members of various sophisticated noble families conspired to benefit both politically and financially by using Celestine as their pawn, the former monk was more concerned about attaining his own salvation—and when he became convinced that his own soul was at risk so long as he was on the papal throne, Celestine V resigned. This Pope, who ruled little more than five months, had never been suited (either tempermentally, or by his education and experience) for the enormous task of ruling the Church. Many theologians and historians disagree as to whether Celestine V—who was subsequently canonized a saint—did the right thing by resigning, because this saintly man might have been able to clean up much of the political corruption that was rife in the Church of the Middle Ages; but the fact remains that he did step down, allowing another Pope to be elected in his place.

Fortunately, this was an extraordinary situation in the life of the Catholic Church! While the Church subsequently did experience other tremendous upheavals and unusual circumstances surrounding the papal selection-process (the Western Schism in the 14th-15th centuries is a sad example), the College of Cardinals has never chosen a new Pope in this strange manner again.

In great contrast to the inexperienced monk-turned-Pope Celestine, the former Cardinal Ratzinger worked for decades as both a diocesan bishop and a Vatican official. Taken together with his legendary expertise as a theologian, his background hardly rendered him ill-suited for the papacy in the way that Pietro Angelerio was. Thus drawing any comparisons between the Pope St. Celestine V, and Pope Benedict XVI, is far-reaching at best! Instead of wondering and watching curiously to see whether Pope Benedict will ever resign, perhaps it would be better to concentrate our efforts on praying that he may continue governing the Church in a manner pleasing to God, and for as long as God wills.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.