Q: We have a lot of confusion in our parish…. Complicating the equation, our diocesan bishop has retired and the Pope has yet to name his successor. We have a diocesan administrator, but he is also currently the bishop of [the diocese right next to ours]. The bishop-administrator is taking very much a “hands-off” approach to running our diocese… laypeople have tried to contact him regarding other matters and he told them to wait for the new bishop to arrive. So many of us have begun to despair of resolving our parish problems…. Do you think maybe we should contact Rome? —Marie

A: There are a couple of separate issues in Marie’s query. The problems in her parish are unclear and thus will not be addressed here, but the issue of alleged inaction by the administrator of her diocese is worth exploring. When a diocesan bishop dies or otherwise leaves office, who runs the diocese until a new bishop is named by the Pope, and what does he actually have authority to do during this interim-period? Let’s take a look.

When an episcopal see becomes vacant, a new diocesan bishop is chosen by the Pope (although there exist several dioceses in German-speaking regions of Europe where the clergy of the cathedral are traditionally permitted to elect their new bishop, who then must be confirmed by the Pope), as per canon 377.1; see “How are Priests Selected to be Bishops?” for more on the process. Episcopal sees can become vacant for several different reasons: the current bishop could die, or submit his resignation and have it accepted, or be removed from office. As a general rule, choosing a bishop’s successor almost invariably takes some time, which means that dioceses are frequently left temporarily without a bishop.

If the diocese has an auxiliary bishop (defined and discussed in “Bishops, Coadjutors, and Auxiliaries”), canon 419 tells us that he assumes governance of the diocese, and is to convoke the diocese’s college of consultors. As we saw in “Canon Law and Bishops of Bling,” every diocese is required to have a college of consultors, which is composed of between six and twelve diocesan priests chosen by the bishop for a five-year term. The college is to meet no more than eight days after the episcopal see becomes vacant, in order to elect a diocesan administrator (c. 421). This administrator then takes charge of the diocese until the Pope names a new bishop.

But there is a possible variation to this procedure, which is mentioned in passing in the abovementioned canon 419. This canon states that the college of consultors is to take charge of the diocese and act as just described, unless the Holy See has provided otherwise. And it often happens that the Holy See (i.e., the Pope) does just that: instead of waiting for the college of consultors to elect an administrator, the Pope can name one himself. In this case, he is known as an apostolic administrator, although his function is the same as that of a diocesan administrator elected by the college of consultors. Here is a good example of just such a situation, from several years back. It appears that in Marie’s diocese, the Pope chose to name a bishop from a nearby diocese as the apostolic administrator, which means the bishop now has two full-time jobs: in addition to his regular duties as bishop of his own diocese, he now has the added (temporary) responsibility of administering the diocese next door.

Now that we can see who has authority over a diocese when there is no bishop, let’s examine what it is that he is able to do. Canon 427.1 states that a diocesan administrator has the power of a diocesan bishop, excluding those matters which are excepted by their very nature or by the law itself. And there are a number of things which the law specifically does not permit an administrator to do. He cannot make major personnel-changes in the Marriage Tribunal, for example, removing the Judicial Vicar and/or adjutant Judicial Vicars from office (c. 1420.5), since this is exclusively the purview of the diocesan bishop himself. Nor can an administrator remove the diocesan Chancellor from office, unless the college of consultors has granted their consent (c. 485). And he cannot name new pastors of parishes, unless the bishop’s see has already been vacant for one year (c. 525 n.2). There are other limitations on the role of the diocesan administrator, and they all serve to underscore a general statement found in canon 428.1: while the episcopal see is vacant, no innovations are to be made.

This is only common sense. No one but the diocesan bishop himself should be engaged in any sort of major overhaul within a diocese—and so when the diocese has no bishop, its administration should ideally be functioning in a routine, ordinary way, on a sort of “auto-pilot.” When the new bishop arrives, he and only he can decide to radically reorganize his chancery staff and reassign chancery officials, rearrange parish boundaries and create new ones (c. 515.2), establish new diocesan Catholic schools (cf. c. 802), and make other significant changes in the diocese.

It appears that this fact is key to understanding the situation in Marie’s case. The current administrator is not simply busy in his own diocese; he also knows that he does not have the authority to tinker with the internal workings of Marie’s diocese in any major way. Thus he could not remove the pastor of her parish, for example, or reorg the clergy-personnel arrangement there. To be sure, if there were a grave abuse going on in Marie’s parish, such as sacrilegious treatment of the Eucharist or some sort of invalid administration of the sacraments, the administrator would of course be duty-bound to intervene and put a stop to it—but nothing of such great magnitude is at issue there.

It’s worth noting that in some cases, a diocesan administrator might privately be aware that a new bishop is going to be named very soon, and so his disinclination to meddle in diocesan affairs would be all the stronger. This seems to have been the case in Marie’s diocese, where a new bishop was named within a relatively short period of time.

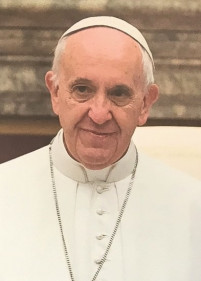

Incidentally, by this point it should be fairly clear that the Pope’s recent acceptance of the  resignation of Cardinal Donald Wuerl, Archbishop of Washington, D.C., in reality amounted to little more than legal semantics—because in the letter Pope Francis wrote to announce that he was accepting Cardinal Wuerl’s resignation, he also named Wuerl the apostolic administrator of the Archdiocese! While there is, of course, a definite canonical distinction between the two titles, in actual practice there is little concrete difference between being the Archbishop of Washington, and being its apostolic administrator. The faithful of Washington can therefore expect to see almost nothing change in the way their archdiocese is operating, until a new archbishop is officially named. And there is nothing in Pope Francis’ letter which would necessarily indicate that a new archbishop will be arriving any time soon.

resignation of Cardinal Donald Wuerl, Archbishop of Washington, D.C., in reality amounted to little more than legal semantics—because in the letter Pope Francis wrote to announce that he was accepting Cardinal Wuerl’s resignation, he also named Wuerl the apostolic administrator of the Archdiocese! While there is, of course, a definite canonical distinction between the two titles, in actual practice there is little concrete difference between being the Archbishop of Washington, and being its apostolic administrator. The faithful of Washington can therefore expect to see almost nothing change in the way their archdiocese is operating, until a new archbishop is officially named. And there is nothing in Pope Francis’ letter which would necessarily indicate that a new archbishop will be arriving any time soon.

Returning to Marie’s situation, there is no question that it can be frustrating when the resolution of significant diocesan issues has to be put on hold, because the diocese is awaiting the appointment of a new bishop. But there are things which rightly should not be tinkered with by temporary officials, since they are so substantial that they can be handled only by the bishop himself.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.