Q1: We’re from Michigan, and the invalid baptism of Father Matthew Hood in the Detroit Archdiocese is all over the Catholic news … lots of people are now wondering if their children were invalidly baptized too, or even if their own baptisms were performed invalidly. Others are saying we should all leave it to God and not worry about it. What should we do if we’re not sure our children’s baptisms are valid? It doesn’t seem right for the Church to leave us in uncertainty after what’s happened to Fr. Hood…. Can we insist that they be baptized again conditionally? –Nicole

Q2: In light of this recent news story, it struck me that this would be a good topic for a post. Hard to believe the Archdiocese took such a hard-nosed position. Seems they could have found the priest’s baptism to be illicit but valid. –Mike

A: If you’re from the United States, odds are high that you’re already very familiar with the particular situation referenced by our two questioners. But for the benefit of readers in the rest of the world, we’ll briefly recap what recently happened in Michigan, and then we can address the specific issues that it has raised among many Catholics in the U.S. and elsewhere. Since, however, the story centers around what constitutes a valid baptism, let’s first look at what the Church teaches on this subject.

The Church has an official, established ritual for baptism that has been approved by Rome and is found in the liturgical books used by Catholic clergy all around the world—and they’re expected to follow it. As canon 846.1 explicitly tells us, no one is to add, omit, or alter anything in the liturgical books on one’s own authority. There is a good reason why the sacraments are celebrated the way that they are: the Church has determined that the rites which it has approved are theologically sound and the sacraments are in this way validly administered. Thus following the ritual found in the liturgical books is obligatory, and there is no room for “creativity” of any kind.

As we saw in “Why is This Method of Baptizing Invalid?” and “Why is This Method of Baptizing Illicit?” tinkering with the approved manner of pouring baptismal water can render the sacrament invalid, or at least illicit (see “Are They Really Catholic? Part II” for a thorough discussion of the distinction between validity and liceity). And as was discussed at length in “Inclusive Language and Baptismal Validity,” playing around with the required formula of words for baptism can invalidate a baptism too. The Church’s approved liturgical books assert that the proper words for baptism are “I baptize you in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,” and this is a requirement, not a suggestion.

Nevertheless, as far too many Catholics are well aware, there are a frightening number of Catholic clergy out there nowadays who, in their arrogance, apparently think that when it comes to the words used in administering a sacrament, the Church’s official liturgical books may very well tell them what they’re supposed to say … but they have a better idea. This attitude isn’t unique to celebrations of the sacrament of baptism, either: we looked at comparable abuses that invalidate the sacrament of Penance in “Is My Confession Valid, If the Priest Changes the Words of Absolution?”

Sometimes the alteration is so obviously wrong from a theological standpoint that it would be hard to find anybody who would argue in favor of its validity. If, for example, a cleric celebrates a baptism which fails to mention all three Persons of the Trinity, that wording is unquestionably invalid and no reasonable Catholic (or other Christian) theologian would suggest otherwise! Such a formulation violates Christ’s own command to the Apostles:

Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit (Matt. 28:19).

But the (in)validity of other ways of tweaking the words of baptism is sometimes less than clear, and it can sometimes happen that orthodox Catholic theologians and canonists find themselves in confusion, if not outright disagreement. As Catholics, whenever we’re faced with such a situation, we turn to Rome for a definitive statement. That’s what evidently happened in the case in question.

In June 2020, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) issued a response to a dubium that had been submitted by a person or persons unknown. The question asked was this: if a person is baptized with the words “We baptize you in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,” is the baptism valid? And the CDF’s answer was a definitive no.

In its accompanying commentary, the CDF noted that theologically there was nothing new about this question—in fact, it had already been raised in the abstract and discussed in the 13th century, by none other than the great St. Thomas Aquinas himself. In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas examined the theological implications of saying “we baptize” instead of “I baptize”:

…[B]y this form, “We baptize thee,” the intention expressed is that several concur in conferring one Baptism: and this seems contrary to the notion of a minister; for a man does not baptize save as a minister of Christ, and as standing in His place; wherefore just as there is one Christ, so should there be one minister to represent Christ. Hence the Apostle says pointedly (Ephesians 4:5): “one Lord, one Faith, one Baptism.” Consequently, an intention which is in opposition to this seems to annul the sacrament of Baptism. (III, q. 67, a. 6, co.)

Note that Aquinas didn’t come out and say directly, “using the form ‘We baptize’ is  invalid,” contenting himself with observing only that it “seems to annul the sacrament of Baptism.” This doesn’t necessarily mean that Aquinas was unsure of himself; rather, if anything it indicates his humble awareness that no matter how famous he had become as a Catholic theologian, he had no authority to make any magisterial statement about sacramental validity that could be considered binding on all Catholics around the world. That task always falls to the Pope, as per canon 841 (and see “Who Decides What Constitutes a Valid Sacrament?” for more on this).

invalid,” contenting himself with observing only that it “seems to annul the sacrament of Baptism.” This doesn’t necessarily mean that Aquinas was unsure of himself; rather, if anything it indicates his humble awareness that no matter how famous he had become as a Catholic theologian, he had no authority to make any magisterial statement about sacramental validity that could be considered binding on all Catholics around the world. That task always falls to the Pope, as per canon 841 (and see “Who Decides What Constitutes a Valid Sacrament?” for more on this).

Aquinas’ position on the invalidity of these words is firmly held by the CDF, which notes,

When the minister says “I baptize you…” he does not speak as a functionary who carries out a role entrusted to him, but he enacts ministerially the sign-presence of Christ, Who acts in his Body to give his grace and to make the concrete liturgical assembly a manifestation of “the real nature of the true Church,” insofar as “liturgical services are not private functions, but are celebrations of the Church, which is the ‘sacrament of unity,’ namely the holy people united and ordered under their bishops.”

Moreover, to modify the sacramental formula implies a lack of an understanding of the very nature of the ecclesial ministry that is always at the service of God and His people and not the exercise of a power that goes so far as to manipulate what has been entrusted to the Church in an act that pertains to the Tradition. (Emphasis added)

Read that last sentence again, especially in light of the recent and unprecedented worldwide closing of churches, cancelling of Masses, and withholding of the sacraments from the faithful “because of the virus” (discussed in “Do Bishops Have the Authority to Cancel Masses Completely?” as well as “What Happens When the Clergy Refuse to Baptize, Because of the Virus?” “Can We Be Required to Wear Masks at Mass?” and “Refusing a Funeral Mass, Because of the Virus,” among many others). The point which the CDF is making here is applicable on multiple fronts and cannot be emphasized enough: when a cleric regards his ministry as an “exercise of power” and not an “ecclesial ministry that is always at the service of God and His people,” he feels free to unlawfully change the rules as he sees fit—with the result (as we can all see too well!) being either an invalid/illicit celebration of the sacraments, or a refusal to celebrate them altogether. The end-result, of course, is that one way or another, the faithful get hurt.

It’s interesting to observe that up until just this summer, the Vatican never made any sort of authoritative statement on this particular baptismal-wording issue. That’s likely because Catholic clergy are expected to use the words of baptism that are prescribed in the approved liturgical books—and for centuries, as we know, they’ve been doing just that. It would appear that in the grand scheme of things, over the nearly 2000-year history of the Church, the tendency among far too many clergy to play fast-and-loose with the administration of the sacraments is a relatively recent phenomenon. The CDF document caustically describes clergy holding such notions as having “debatable pastoral motives,” adding that “often the recourse to pastoral motivation masks, even unconsciously, a subjective deviation and a manipulative will.”

The CDF also cites the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium, which unequivocally asserts who has the authority to make changes to the Church’s liturgical rites—and who doesn’t:

Regulation of the sacred liturgy depends solely on the authority of the Church, that is, on the Apostolic See and, as laws may determine, on the bishop…. Therefore no other person, even if he be a priest, may add, remove, or change anything in the liturgy on his own authority (SC 22).

By now it should be evident that Mike’s criticism the Archdiocese of Detroit is completely unfounded, because the invalidity of the altered words of baptism was determined by Rome, not by a single archdiocese on the other side of the world. It should be equally clear that this is a matter of theology, not of being “hard-nosed” (whatever that even means in this context). Before launching an attack, it is best first to be sure that you’re aiming at the right target.

Now that we’ve seen what the supreme authority in the Church teaches on this subject, let’s move on to the specific case which has held the attention of so many American Catholics in recent weeks. In the Archdiocese of Detroit, Michigan, a diocesan priest named Fr. Matthew Hood was watching a video of his own baptism as an infant, and was immediately struck by the words used by the permanent deacon who baptized him: Deacon Mark Springer clearly used the words “we baptize you” rather than “I baptize you.”

The chronology of subsequent events has been inconsistently reported by various news media, with some suggesting that the priest saw the video before the CDF issued its statement, while others stated that he had done so later. But what we do know is that Fr. Hood contacted the diocesan chancery, and to everyone’s chagrin, it became clear that in accord with the CDF’s statement, Father’s baptism had not been administered validly—because a deacon had taken it upon himself to change the Church’s approved formula of words for baptism.

What does this imply? Well, canon 849 tells us that baptism is the gateway to the sacraments, meaning that you cannot validly receive any of the other sacraments if you are not baptized first. This means, logically, that none of the other sacraments which Father Hood thought he had received in his lifetime had been administered validly either—including, of course, the sacrament of Holy Orders (cf. c. 1024, which asserts that only a baptized male can be ordained validly, and see “Can a Priest Have His Ordination Annulled?” for more on this). Through absolutely no fault of his own, “Father” Hood was not a priest at all.

Since he had already been engaged in parish ministry for several years, the practical implications of this news were/are staggering:

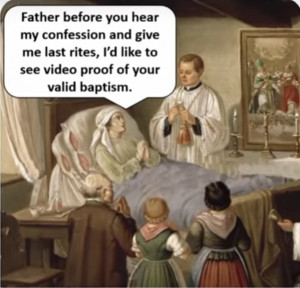

1) None of the confessions ever heard by Fr. Hood were valid, since he was incapable of granting absolution (c. 965, and see “Can All Priests Always Hear Confessions?”);

2) None of the Masses Fr. Hood had ever celebrated were valid (as per c. 900.1), which means that everyone who received the Eucharist consecrated at his Mass, really didn’t receive the Body and Blood of Christ at all—and it also means that every Mass which he had celebrated at the request of someone who had given a stipend for that purpose was not in fact celebrated (see “Mass Intentions and Stipends, Part I” and “Part II” for more on this subject);

3) Fr. Hood never validly married anybody (cf. c. 1108.1, and see “Why Can’t These Priests Celebrate a Valid Catholic Wedding?” and “Our Priest Cancelled Our Wedding, So Who Else Can Validly Marry Us?” for more info), nor did he ever validly confirm anyone (“Can a Priest Administer the Sacrament of Confirmation?” addresses the situations when a priest can confirm), or ever validly celebrate the Anointing of the Sick (cf. c. 1003.1).

Needless to say, Fr. Hood himself was not at all to blame for any of this—nor were any of the faithful who reasonably thought that they were receiving the sacraments from him.

Ironically, the one sacrament which he validly celebrated was the one he himself had received invalidly at the start: the baptisms administered by Fr. Hood were valid, because (as we’ve seen in “Do Converts Have to be Rebaptized?” and “When Can Catholic Soldiers Receive Sacraments From Non-Catholic Chaplains?”) anybody with the right intention can validly baptize (c. 861). That of course includes people who haven’t been baptized themselves.

What a mess! The exact number of Catholics who have been affected in some way or another by this one incident is impossible to calculate. And it all began with a permanent deacon who didn’t feel like correctly following the Rite of Baptism as found in the Church’s approved liturgical books, because he thought he could improve upon it.

Speaking of which, it goes without saying that if Deacon Springer altered the formula of words at the baptism of the infant Matthew Hood, he undoubtedly did the same at other baptisms which he celebrated. And every single person whom he invalidly baptized has subsequently received any and all other Catholic sacraments invalidly too. That likely includes marriages—which in turn means that this affects even some validly baptized Catholics, whose spouses had been invalidly baptized by Deacon Springer (on this topic, see “Marriage between a Catholic and a Non-Catholic” for the basics on how this works).

Now that this situation has become public knowledge, the Archdiocese of Detroit has been taking steps to correct it. Father Hood was baptized properly, and then received all the other sacraments, including that of Holy Orders, so now he really is a Catholic priest. The Archdiocese has contacted the couples whom he had invalidly married or confirmed, so as to rectify their situations as well.

As for all the other people invalidly baptized by Deacon Springer, the Detroit Archdiocese has likewise been attempting to locate them all, to tell them what’s happened and baptize them validly. Considering that lots of these people have undoubtedly moved away and may be impossible to find so many years after the fact, this is a herculean task—which nevertheless has to be done as a matter of charity.

And speaking of charity, here’s where things get interesting.

The Archbishop of Detroit, Allen Vigneron, issued a letter to all the faithful explaining what had happened, and among many other things he says this:

The deacon who first attempted to baptize Father Hood, Deacon Mark Springer, used this invalid formula while assigned at St. Anastasia Parish in Troy, [Michigan,] during the period from 1986-1999.

Why did the deacon stop doing this in 1999, you may be wondering? In an accompanying list of Frequently Asked Questions posted by the Archdiocese, we find this illuminating question and answer:

What happened to Deacon Springer?

Deacon Mark Springer, who had performed the invalid baptism [of Matthew Hood] was approached by Archdiocesan officials in 1999 when they had learned that he was using the pronoun “We” instead of “I” during baptisms. He was forbidden to continue using the improper formula at that time and has stated that he has abided by that directive ever since. At the time, after careful study and canonical counsel, those entrusted with this situation believed the baptisms to be valid. It was only on August 6, 2020 that the Archdiocese received notice confirming the invalidity of the words used by Deacon Springer.

Deacon Springer is retired and no longer in active ministry. (Emphasis added)

Whether you realize it or not, the italicized sentences here are a veritable masterpiece of equivocation, so let’s look at them carefully. Back in 1999, somebody finally reported Deacon Springer’s incorrect baptismal wording to unnamed “officials” of the archdiocese, after he had already been baptizing in this way for thirteen years. These “officials” were evidently disturbed enough to do some sort of research into the validity (or not) of a baptism performed using the words “we baptize you.”

The statement asserts that “those entrusted with this situation” (and who were they?) “believed” that the baptisms were valid (meaning they simply took it on faith? or what?), after “careful study and canonical counsel” (from whom?). So according to this statement, that was the end of it, and no action was taken other than to tell Deacon Springer to stop doing this, and trust him not to do it again.

Well, as we’ve already seen above, until a few weeks ago the Catholic Church did not have any formal, official position on the validity of a baptism performed using the words “we baptize you,” although the Church’s top theologian personally held many centuries ago that it was invalid. If “those entrusted with this situation” did some “careful study,” they logically should have found Aquinas’ statement, and noted that over the course of the subsequent 700+ years, the Church had never found fault with it in any authoritative way—and surely that means something.

And if “those entrusted with this situation” had indeed sought “canonical counsel,” it’s hard to imagine how a competent canonist could have found any grounds upon which to base a confident reply that “yes, baptisms using the form ‘we baptize you’ are valid.” On the contrary: the best thing that any responsible canon lawyer could say might be, “I’m not sure … but it doesn’t look good.” Consequently, genuine “careful study and canonical counsel” should have led these unnamed archdiocesan “officials” to request an authoritative statement from the CDF—because only this would provide an answer upon which the Archdiocese of Detroit (as well as the rest of the universal Church) could truly rely.

If this had been done back in 1999, rest assured that the CDF would not have spent 21 years studying the question—and so we would all have had the authoritative answer to the question long ago. In fact, it would have been resolved long before Matthew Hood had ever sought ordination to the priesthood, so this whole mess would never have even happened!

The oh-so-careful wording of the archdiocesan statement is clearly meant to deflect attention from the person(s) in the chancery who back in 1999 failed in their duty to ensure that all the faithful of the Archdiocese of Detroit were indeed receiving the sacraments validly. This was also, as noted above, a matter of charity to others—and in this, the greatest of the three theological virtues (cf. 1 Cor. 13:13), these unnamed “officials” failed grievously.

Archbishop Vigneron was not in Detroit in 1999; at that time, the Archbishop of Detroit was Cardinal Adam Maida. It is interesting that his name doesn’t seem to be coming up anywhere, as he was and is the one who must ultimately be held responsible for this scandalous fiasco. But like Deacon Springer, he is retired, and at least publicly he is not being held at all accountable for his (in)actions. Note that the universal Church takes all this much more seriously than certain “officials” of Detroit appear to: as canon 1379 tells us, simulating (invalidly) the administration of a sacrament is a crime.

In “When (and How Much) Can a Bishop Tax a Parish?” we saw that these days there are countless Catholics who refuse to donate a cent to their dioceses, because of the ways their bishops have been mishandling those donations, or have otherwise been conducting themselves. At the root of all the various scandals and abuses is the undeniable fact that for far too long, diocesan bishops have not been held responsible for what they do, or fail to do. This means that in effect, these men hold tremendous authority and frequently have control over large numbers of people and enormous sums of money … and they know they can do whatever they wish with it all, with total impunity.

(Remember the original “Bishop of Bling,” Limburg, Germany’s Bishop Franz-Peter Tebartz-van Elst? As we saw in “Canon Law and Bishops of Bling,” it appeared that he was removed from his office as a punishment for his scandalously extravagant personal expenditures—but if you think he was really “punished,” see here and here for a look at what he is doing nowadays.)

No matter what damage such bishops do to either the material wellbeing of the dioceses they operate, or the spiritual wellbeing of the souls committed to their care, they rest assured that they will always be allowed to retire with honor and live on a pension provided by the Church; and if their deeds come to light, their successors will cover for them. How many laypeople can say the same about their own fields of work?

Every single seminarian around the world should be required to study the case of what happened to Father Matthew Hood, because it needs to be drummed into all of them at an early stage that when a cleric plays games with the sacraments, because he lacks “an understanding of the very nature of the ecclesial ministry that is always at the service of God and His people and not the exercise of a power that goes so far as to manipulate what has been entrusted to the Church” (as the CDF statement phrases it), innocent people suffer. Even when they aren’t suffering because they thought they’d received sacraments which now turn out to be actually invalid, they suffer because their trust in their clergy is gravely damaged, and understandably so. Nicole’s question perfectly illustrates this fact: if  Deacon Springer willfully used invalid baptismal language for at least thirteen years, how do we know that other priests and deacons didn’t do the same thing?

Deacon Springer willfully used invalid baptismal language for at least thirteen years, how do we know that other priests and deacons didn’t do the same thing?

Strictly speaking, unless you can remember what words the priest used at your own or your child’s baptism, or like the Hood family you have a video of it and can double-check, you don’t know. And in such cases as these, where it is humanly impossible to determine whether anything was amiss, and we have no specific reason to suspect invalidity, we can only entrust the situation to God and assume that all is well. The notion that we and/or our children should all be conditionally rebaptized “because maybe” is irrational—and in any case, how could you be absolutely sure that there wouldn’t be a different sort of invalidating problem the second time around?

There is a Catholic bishop currently heading a diocese in the former Soviet Union, who doesn’t know the date of his own baptism … since he was baptized three different times. Because of communist persecution of the Church in his region at the time of his birth, he was baptized as an infant by his mother in the kitchen sink—which under the circumstances was entirely permissible, as we saw in “Laypeople Can Always Baptize—But When Should They?” and “What Happens When Clergy Refuse to Baptize, Because of the Virus?” After all, there was no priest in the vicinity and the parents didn’t know when one would come.

But the mother later began to have scruples that for whatever reason (or no reason), maybe she didn’t do the baptism correctly. She was so unsure that her husband, the baby’s father, took it upon himself to baptize the baby conditionally himself. So one would presume that if the baptism wasn’t valid the first time, at least the second time it was done right.

Unfortunately, the baby’s father subsequently had scruples of his own! He started to worry (again, for unclear reasons) that he hadn’t baptized the baby properly either. The couple were in this state of uncertainty until finally a Catholic cleric arrived in their town. They brought the baby to him, explained the situation … and he baptized the baby conditionally again. With that, everyone was satisfied.

If the mother’s baptism of the baby was valid, the other two conditional ones were unnecessary and had no effect. Likewise if the father’s conditional baptism was performed correctly, the third time was superfluous. In any event, we may all reasonably assume that at some point this poor child was really baptized a Catholic—but we don’t know when it was.

The point is this: we can’t all go around worrying constantly about sacramental validity if we don’t have particular, substantive grounds for doing so. Even a conditional baptism can, as in the case of this future bishop, be insufficient to quell people’s fears! Unless you or someone else actually knows that something was wrong with the way your baptism was administered, or you get a phone call from your diocese (as has happened to people invalidly baptized by Deacon Springer) specifically telling you otherwise, the only rational thing to do is assume that the sacrament was celebrated validly.

God is not bound by the sacraments, or by canon law—although we Catholics are. He can, if He wishes, work outside the boundaries set by His Church, in whatever way He wants. After all, as the Catholic theologian interviewed in this article rightly observed, Matthew Hood was led by God’s grace to embrace the priesthood—even though at the time he hadn’t even been validly baptized yet! There are likely people out there who (for example) confessed their sins to non-Father Hood and later felt wonderfully relieved to know that God had forgiven them … and since both priest and penitent in this sort of cases were acting in true sincerity, it is not for us to claim that “God didn’t forgive those sins.” But what we Catholics (and especially canon lawyers) can say is that in a situation where we know that a sacrament was not celebrated in a way that the Church says is valid, it has to be celebrated again correctly.

Let’s regard this tragic situation in the correct light, without panicking needlessly, and learn from it. Catholic sacraments are not toys, and their validity matters—which in turn means that the Catholic clergy have a tremendous responsibility to the faithful when administering them. And if nonetheless they deliberately choose to play around with the sacraments of the Church … their actions should have consequences.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.