Q: At Sunday Mass, Father announced that the church pipe organ was going to be replaced by a digital organ, because the pipe organ was in very bad shape. He said that he was given an anonymous gift of $100,000 to do this, and the contract has already been signed. This was the first I had heard of this. I attend the parish council and parish finance committee meetings and this was never discussed. The people of the parish have already donated $22,000 to fix the pipe organ.

I did learn that the Bishop must approve purchases over $10K, and he must also approve any change to the interior of a parish church, such as changing out the organ. The pastor later told me that the Bishop gave him permission to remove the existing organ and to purchase a digital organ.

Does the pipe organ constitute church property which the pastor has only limited control over, specifically, can I insist that the old pipe organ parts be stored rather than thrown out or, what I’m afraid of, sold for big bucks? And can I insist just as a regular parishioner, to know what happens to the old pipe organ parts, and whether it is sold? It certainly has a “value” and I am just afraid that it’s being sold out from under us and that Father has unwisely settled for a fake sound-maker. –Dave

A: It’s a common enough scenario, isn’t it? Parish priests and their parishioners frequently clash over the “best” way to handle parish finances in general, and major expenditures like this one in particular. On the one hand, the pastor correctly asserts that he alone—and not the members of the parish—is in charge of running the place, including the buying and selling of parish property. But on the other hand, parishioners often find sound reasons to object to the pastor’s financial management (or lack thereof), rightly pointing out that they’re the ones who provide the parish with monetary support.

There are several different legal issues intertwined in Dave’s question, and so it’s necessary to distinguish them and address them in turn, before coming to any conclusions about this situation. For starters, let’s look at the authority of the parish council and the parish finance committee, since Dave mentions he is a member of both.

As was discussed in “Canon Law and Parish Councils,” the pastoral council (often known as a parish council) and the parish finance committee are two separate entities. The first one is optional, since it is up to the diocesan bishop to determine whether such councils are appropriate in the parishes of his diocese (c. 536.1). Thus pastoral/parish councils might not even exist in a given diocese. But if they do, its members have only a consultative vote, meaning that their vote on any particular issue is not binding on the pastor of the parish (c. 536.2). The members of this council may strongly recommend that the pastor do something, but the ultimate decision is always his.

In contrast, a parish finance committee is required by law in every parish, as per canon 537. Nevertheless, its members likewise have only a consultative vote, as explained in the Vatican’s 1997 Instruction on Certain Questions Regarding the Collaboration of the Non-Ordained Faithful in the Sacred Ministry of Priest (Art. 5.2). While he is certainly expected to listen to the opinions of finance-committee members, the final decision on parish monetary questions is always the pastor’s, as he alone may act on behalf of the parish in such matters (cf. c. 532).

With regard to finance committees, there is a twist, however: canon 537 notes that the parish finance committee is to be run in accord with the norms laid down by the diocesan bishop. And diocesan bishops can (and do) establish their own diocesan regulations, obliging parish priests to obtain permission from the bishop before buying church property costing more than a certain set amount. In Dave’s diocese, the amount is $10,000; so if any pastor wishes to purchase something that costs more than that, he must first get the bishop’s approval. In this case, it is indeed odd that the pastor never discussed the purchase of a new organ with the parish finance council—but he is apparently on solid legal ground anyway, since the bishop approved the proposal.

There are obvious reasons why a bishop would want to know what major expenditures his clergy are making in the parishes of his diocese—and to be able to block them if he saw fit. Priests are, after all, trained in philosophy and theology, not in finance; so it’s not inconceivable that a pastor might know absolutely nothing about how best to go about replacing a roof or a furnace, determining what such things normally cost and which vendor will do the best job. The parish finance council should logically be able to advise him in such matters, but as we have just seen, the pastor is not actually bound to accept their recommendations. He is, however, required to obey his bishop! In this way, there are limitations on what a parish priest can do with parish funds. If Dave’s pastor were somehow snookered by a dishonest organ dealer, who quoted the parish a ridiculously high price for a new electronic organ, the need to submit this proposal to the bishop in advance ought (at least in theory) to ensure that a blatantly bad financial decision would be spotted before it’s too late.

A necessary component of this major financial expenditure, of course, is the “anonymous gift” of a hefty sum earmarked for the purchase of a new organ. We saw in “Canon Law and Donations to the Church” that if someone makes a donation for a specific purpose, the intentions of the donor are to be carefully observed (c. 1300). Thus if Father has accepted the donation for the purpose of buying a digital organ, he cannot use that money for anything else. Consequently, if he had failed to obtain the bishop’s permission for this purchase, the pastor would have had to refuse to accept the donation, or return the money to the donor if he had already accepted it.

But note that in the meantime, it seems that other parishioners have donated a total of $22,000 for repair of the existing organ, and evidently their donations have already been accepted too. Since the purpose of their donations is the opposite of the $100,000 donation for the new digital organ, it’s logically impossible for the pastor to use all these funds for their intended purposes! As he clearly wants to replace the pipe organ instead of repairing it, the $22,000 contributed by parishioners specifically for organ-repairs must be returned to them, unless the donors indicate that the parish can keep their money to pay for other things.

Yet another issue is the fact that the pastor of Dave’s parish intends to sell the pipes and other components of the original organ. Dave is quite right that even if the pipe organ is in need of repairs, its parts may nonetheless be extremely valuable. And just as there are church laws regarding large purchase of property, there are also laws concerning the sale of church property to others. In canon law the term used to refer to such sales is alienation.

Once again, the bishop has the authority to lay down norms governing the alienation of anything belonging to a parish of his diocese. If he has established that nothing may be bought for more than $10,000 without his approval, it’s likely that he’s also established a similar cut-off requiring his approval when property is sold. Thus if the pieces of the old pipe organ are to be alienated for more than the minimum amount established for the diocese, the pastor probably needs to get the bishop’s permission to do this first.

Dave doesn’t fully explain his concerns, but he may be worried the pipe-organ pieces may be sold off for less than their actual worth. Canon 1294.1 notes that in general, church goods should not be alienated for a price that is lower than their valuation. It’s certainly possible that an unscrupulous dealer might have convinced the priest—who is presumably no expert on the subject—that the old organ pipes are worth far less than they really are! In such a situation, we may reasonably hope that the diocesan norms provide that this pastor must first obtain approval from the diocesan bishop for the sale, and the bishop should then double-check that the amount which the parish will get for the organ parts is more or less what they’re worth.

If Dave and the other members of the parish finance council conclusively establish that the pastor intends to sell the old organ for a fraction of its actual value, they obviously should object strenuously to the pastor’s plans; and if the priest refuses to listen to their concerns, they can always contact the bishop and alert him to the situation. But if the pastor wants to sell the organ parts for a reasonable price, the parishioners—even if they’re on the parish finance council—cannot micromanage him by insisting that the old organ be stored instead.

We can see that managing parish finances can be a real balancing-act. While the pastor is responsible for the operations of the parish, and can make decisions unilaterally on everyday matters, he is expected to confer with the parish finance council on issues of greater importance. Still, while the members of the finance council can and should advise him, they can’t oblige the pastor to do what they want. The decision—and the responsibility for it—are his.

At the same time, the diocesan bishop can require pastors to seek his approval for all major purchases and sales, and he can define exactly what the term “major” means in this context, too. If he disagrees with a pastor’s wish to buy or sell something for the parish, the bishop can always nix it. The interplay of these different people of the diocese—both clergy and laity—is intended to ensure that bad financial decisions are kept to a minimum.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

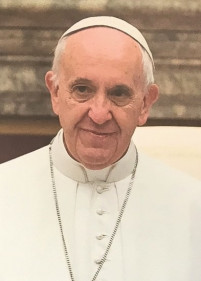

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.