Q: A group of us parents have complained to the pastor about the parish’s Director of Religious Education (DRE) without results. The DRE is a laywoman with complete control over the textbooks and curriculum used in catechism classes, and she removed the textbooks that were used for years, replacing them with a different series which contains nothing but fluff. We parents don’t feel that our children are learning anything substantive about their faith… The pastor told us that the catechism program is the DRE’s responsibility, and he can’t interfere with the way she does her job. Is that true? It doesn’t sound right, since the pastor is the one who hired her… –Karen

A: Many readers may be wondering about the term “Director of Religious Education,” since in quite a few countries such a job-title does not even exist. It is likewise found nowhere in the Code of Canon Law, even though one entire book of the code is called “The Teaching Office of the Church,” much of which pertains directly to the issue of catechetics. Let’s see what the code does say about the religious education of children, and in the process the answer to Karen’s question will become clear.

As was noted in “Homeschooling and Catechetics,” the code echoes the Catechism of the Catholic Church (2221) in noting that parents have the primary right to ensure their children’s religious upbringing (c. 1136). Catholic parents who make zero effort to have their children educated in the faith are therefore eschewing a serious responsibility.

At the same time, the pastor of a parish is, by definition, obliged to see to the Catholic education of children and young people from his parish (c. 528.1). Canon 776 is even more specific, noting that a pastor is required by virtue of his office to ensure the catechetical formation of both adults and children of his parish. The very next canon goes into greater detail, stating that the pastor is to follow the norms established by the diocesan bishop to ensure that children receive a proper religious education, particularly when preparing for their first confession and first Holy Communion (c. 777). In each case, the wording of these canons indicates clearly that it is the pastor’s duty to do this. The fact that the diocesan bishop has given him the office of pastor of a parish automatically carries this responsibility with it. In other words, if a priest is made a pastor, ensuring that the parishioners are educated in their faith is not an optional task for him!

How does a DRE fit into this equation? Well, canon 776 does state that with regard to the religious instruction of both children and adults of his parish, the pastor is to avail himself of the help of (a) other priests assigned to his parish, if there are any; (b) sisters or other members of religious institutes (assuming, of course, that there are some residing in the territory of the parish); and (c) the lay-faithful, especially trained catechists. Such persons are to help the pastor to carry out his responsibility of instructing the people of the parish.

In different parts of the world, the precise manner in which this is carried out may vary. For example, bishops in many African countries have developed systems for training lay-catechists, who are then tasked with helping parish pastors to catechize children, young people, and catechumens. This is in full accord with canon 780, which asserts that it is the job of bishops to ensure that catechists are properly trained in both theology and pedagogy, so that they can carry out this role.

But every corner of the globe has this much in common: no matter how a parish’s religious education is organized, the pastor of the parish is in charge. Within the parameters of any guidelines that may have been issued by the diocesan bishop, is the pastor who always has the final say in deciding whether a certain method of teaching, or a particular textbook is appropriate for the children under his spiritual care. There is nothing arbitrary about this arrangement, as it is grounded in the Church’s basic theological understanding of the role of the clergy as shepherds of souls: as canon 519 points out, the pastor of a parish is responsible for the pastoral care of the parish entrusted to him, since he shares in the ministry of the diocesan bishop. True, the canon adds that other clergy may cooperate with the pastor in this role, and the lay faithful may assist him in accordance with the law—but within the parish, the pastor always has to be at the head.

This explains why, with regard to children preparing to receive their First Holy Communion, the pastor of the parish has the duty to see to it that children whom he has judged to be insufficiently disposed to receive the Eucharist do not do so (c. 914). While a parish’s lay catechists may, in many cases, do the lion’s share of the children’s sacramental preparation, the decision that little Susan or Thomas is indeed ready to receive the sacrament ultimately rests with the pastor.

Assuming that a parish has a team of catechists who are properly trained to teach the children the faith, it may very well be that a pastor leaves the final decision as to a particular child’s readiness to receive the sacraments to the teacher. He may reasonably feel that the catechist (or a DRE) is competent enough to determine whether a student is sufficiently prepared or not! But note that this is totally up to him. A pastor can, if he wishes, quiz the children himself (or devise some other method of assessment) and make the final call on his own, irrespective of the teacher’s opinion. In other words, a pastor can defer to a lay-catechist if he wishes; but he doesn’t have to. And in no case whatsoever does a religion teacher—whether it’s a parent-volunteer, a religious sister or brother, or even a priest assisting the pastor as parochial vicar—have the authority to overrule the pastor. Period.

This is why the response of the Karen’s pastor is so problematic. If the DRE has chosen a textbook-series to be used in teaching the parish children, the pastor certainly has the right—in fact, he has the obligation—to ensure that it is neither heretical, nor an inadequate means of forming the children in their faith. In this case, it may be that the pastor left the decision up to the DRE, reasonably assuming that she was competent to do her job without being micro-managed at every step of the way. But if the decision of the DRE has resulted in an insufficient catechetical formation of the students, the ultimate responsibility for that failure rests squarely on the pastor’s shoulders.

To be fair, if nobody had ever brought the matter to his attention, it wouldn’t be unreasonable for the pastor to presume that everything in the parish’s religious-education program was going well! Karen notes that the pastor had hired this particular DRE, so it’s only logical that he has seen her credentials and believes she is capable of making good decisions about proper catechetical methods and materials. But now that the parents have made a complaint, claiming that their own children aren’t being adequately instructed, it would be irresponsible for the pastor to dismiss their concerns without first investigating the matter himself.

And as we’ve just seen, the suggestion that he, the head of the parish, must defer to the decisions of the DRE who works under his authority is patently false. Father might very well disagree with the concerned parents, and remain convinced that the DRE’s choice of textbooks for the parish children was the right one. But the final decision rests with the pastor, who is specifically charged with the spiritual welfare of all his parishioners— including children in the parish’s religious-education program.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

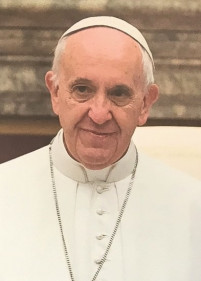

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.