Q: There’s a battle going on in our diocese, between our bishop and a group of sisters who teach in X school…. Does the bishop have the authority to kick a sister out of the diocese, if her Mother Superior insists that she should stay? –Jennifer

A: As we saw back in “Notre Dame, Obama, and the Bishop’s Authority,” the relationship between a diocesan bishop, and members of religious institutes engaged in the apostolate inside his diocese, can get tricky depending on the circumstances. There’s no question that a bishop always has a significant degree of authority when sisters, brothers, or other religious work within the boundaries of his diocese—but that authority is not absolute. Before attempting to answer Jennifer’s specific question, let’s look first at a couple of the different factors that can affect the relationship between a diocesan bishop, and religious sisters operating in his territory.

With a few exceptions, the populated areas of the globe have been divided by the Church into dioceses, with precise territorial boundaries, each headed by a bishop (cf. c. 369). At the same time, there are religious institutes of women engaged in various apostolates all around the world—which means that no matter what sort of work they may be doing, they’re invariably doing it within the territory of some bishop. And that means, in turn, that the bishop necessarily has an interest in the work that these religious perform: as canon 394 notes, the diocesan bishop is to ensure that all works of the apostolate in his diocese are coordinated under his direction. In other words, any group of religious (whether sisters, brothers, or clerical members of a religious institute) that operates schools or hospitals, keeps house for the bishop, prays in a cloistered monastery, etc., is doing this work with the knowledge and approval of the bishop of the diocese where they are located.

The degree of the bishop’s involvement can vary, depending on the situation—and while the specifics are so complex that one could write a book to address them all, it’s possible to make a couple of basic points here. To cite one example, let’s say that St. Peter’s Church, a parish in Diocese X, has its own school, connected to the parish. At some point in years gone by, Bishop Smith of Diocese X asked the Superior of an institute of teaching sisters if she could send several sisters to staff the school, and live in a convent next door. These sisters are, of course, directly responsible to their own Superior; but at the same time, St. Peter’s Catholic School is directly affiliated with St. Peter’s Church, and intended primarily for the children of the parish. As such it is ultimately under the authority of the pastor of St. Peter’s (cf. c. 776), who of course is under the authority of Bishop Smith.

A somewhat different scenario is also very common, in which a group of teaching sisters operate their own school, unconnected to any diocesan parish, but still located in the territory of Diocese X. Again, these sisters are directly responsible to their own Superior, and if operating schools is the primary apostolate of this particular religious institute, they presumably have their own curriculum and teaching methods. Because they operate their school independently, they consequently aren’t under the direct supervision of the pastor of the parish where they happen to be located. Nonetheless, the school exists in Diocese X, only because at some point in the past, the Bishop of Diocese X permitted them to open it there (c. 801). Today, our imaginary Bishop Smith has the right and the duty to oversee and approve of the religious instruction that is being taught there—because the sisters are teaching the children of his diocese, whose spiritual welfare is his responsibility (c. 806.1).

This basic distinction holds true not only with regard to Catholic schools staffed by religious sisters, but also with hospitals, orphanages, retreat houses, homeless shelters, etc. The diocesan bishop always retains some degree of direct interest in, and control over what is being done by these women in his diocese—and if he sees something that causes him concern, he has the right and duty to do something about it.

Another important distinction exists between religious institutes which are of pontifical right, and those of diocesan right (c. 589). In a nutshell, large groups of religious—like Franciscans or Dominicans—are normally institutes of pontifical right, answerable primarily to Rome while they have apostolates in numerous dioceses around the world (c. 593). But there also exist much smaller religious groups (including many new institutes, that were established recently and are just starting to get going), which have only one house, located in a single diocese. If they were founded with the permission not of Rome, but of the bishop of the diocese where they’re located, they are diocesan-right institutes, which means the diocesan bishop has more direct authority over them in many matters (c. 594). Again, this can get complicated, and there’s no need to spell out every single distinction between the two types here. But the point is that the extent of involvement of a diocesan bishop within the activities of religious institutes operating in his diocese can vary. Let’s invent a sample-case, and see how a scenario like that described by Jennifer in her question might play out.

Let’s say that Sister Barbara teaches English literature at Holy Rosary High School, operated by her religious institute of pontifical right, the Sisters of the Mountain-Top, in the Diocese of X. She’s an excellent teacher and is popular among the students; but she has begun writing and speaking publicly about the role of women in the Church—and now her articles and lectures are openly criticizing the Pope and others in the Catholic hierarchy, and directly attacking church teachings. Since Sister Barbara always identifies herself as a teacher at Holy Rosary in Diocese X, her readers/listeners naturally begin to wonder if her stance is also officially embraced by all the teachers at Holy Rosary High School, by all the Sisters of the Mountain-Top around the world, and also by Bishop Smith, the bishop of Diocese X. Bishop Smith is understandably unhappy with what Sister is doing. What can he do?

Procedurally, the first thing to do is to make contact with Sister Barbara’s Superior, in order to discuss the matter. After all, maybe the Mother Superior of Holy Rosary Convent has been ill, or is brand-new, or is overwhelmed with other responsibilities, and thus has no idea what’s going on! Strictly speaking, it is Sister Barbara’s Superior (not Bishop Smith!) who is directly responsible for her, and who can order Sister to cease and desist. It is for the bishop to outline the problem, and the Superior of this convent of the Sisters of the Mountain-Top to act.

But this is not meant to suggest that in general, every religious superior is required simply to rubber-stamp every complaint and concern of a diocesan bishop, automatically giving him whatever he demands. A superior may very well have a fuller understanding of a given situation than a bishop does, and so might be able to resolve a problem in a manner other than what he expects. It may also be possible that in some cases, a bishop is unwittingly insisting that a religious behave in a certain way/do a certain thing which is contrary to the Rule of his/her religious institute, or which conflicts with what he/she was told to do by a superior(s). The point is, the bishop and the religious superior should be able to have a calm, adult conversation about the perceived problem, ensuring that there is no confusion or misunderstanding on either side.

Returning to our imaginary scenario, let’s say that Bishop Smith has multiple, extended conversations with Sister Barbara’s superiors, ultimately including the Major Superior of the entire institute of the Sisters of the Mountain-Top (who resides at their General Headquarters in Rome), yet none of them agrees that Sister’s public statements constitute a problem. Let’s say also that Bishop Smith even provides evidence that Sister Barbara’s pupils—who are members of Diocese X, and thus under his spiritual care—are now getting confused about what the Church teaches about the role of women, because they can’t fathom that their beloved teacher could be making heterodox statements. Bishop Smith insists that either Sister Barbara has to stop writing/lecturing on this topic, or the Sisters of the Mountain-Top must transfer her out of Diocese X.

Speaking generally, at this point a religious superior will most likely strive to find an acceptable compromise, even if he/she doesn’t feel that a bishop’s complaint is really justified. After all, our mythical Holy Rosary High School can’t easily be moved out of Diocese X, and so the sisters who run the school will have to continue dealing with Bishop Smith in the future. Consequently they don’t want to antagonize him!

But let’s say that Sister Barbara’s immediate superiors are so convinced that what she is doing is acceptable, and that Bishop Smith’s criticisms are unfounded, that they are utterly unmoved by his ultimatum. The institute’s Major Superior in Rome likewise thinks the Bishop is overreacting, and she refuses to do anything about Sister Barbara, instead declaring that Sister Barbara will remain a teacher at Holy Rosary, period. By now, Bishop Smith has gone up the entire chain-of-command of this religious institute—there’s no other superior for him to turn to.

At this point, Bishop Smith can act in accord with canon 679, which states that for a very grave reason, if the major superior has been informed and has failed to act, a diocesan bishop can forbid a member of a religious institute to remain in his diocese. Sister Barbara is thus ordered out of Diocese X, and (also as per canon 679) Bishop Smith notifies the appropriate Vatican congregation of what has happened. Rome needs to be made aware of this standoff between a bishop and an institute of women religious; after all, it’s possible that this group of sisters has a track-record of such friction with local bishops—or, alternately, it may be that Bishop Smith is showing signs of unreasonable combativeness with multiple religious institutes in his diocese! In any case, the Vatican has to be informed of the incident by the bishop.

So now we can see the answer to Jennifer’s question. Yes, a bishop can “kick a sister out of the diocese,” but only after certain criteria have been fulfilled, and with Rome being made aware of the whole unhappy situation. Since both bishops and religious are supposed to be working “on the same team,” so to speak, this is a very grave situation, which fortunately doesn’t happen very often. But we can see that the bishop’s responsibility for the spiritual welfare of the faithful of his diocese has to be taken seriously—and if it isn’t, there is a legal mechanism in place for him to excercise an unusual sort of authority with a recalcitrant religious if necessary.

Why is Google hiding the posts on this website in its search results? Click here for more information.

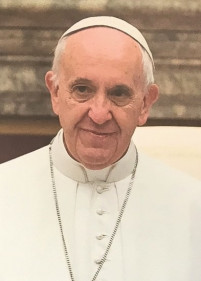

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.

Canon lawyers are not responsible for the content of canon law. The Supreme Legislator is. Only Pope Francis can change the Code of Canon Law, so if you're not happy with what the law says, please take it up with him.